Growing up in #Toronto, I held #NYC in awe. Per the joke, one Torontonian changes the lightbulb, the other goes New York to make sure lightbulbs are still in. I had a *great* place to stay in the City: my cousin Maxine's rent-controlled place in a midtown doorman building.

1/

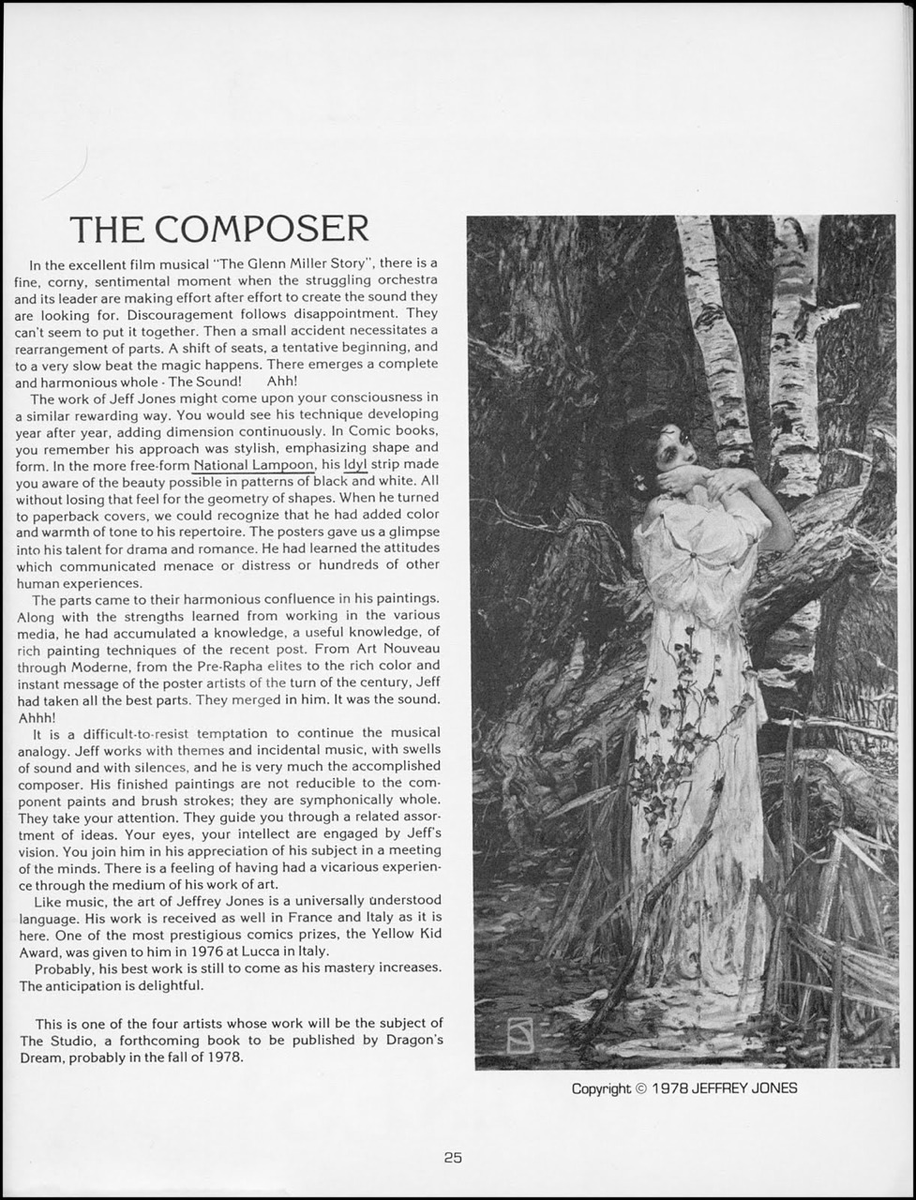

1/

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

pluralistic.net/2023/04/21/bon…

2/

pluralistic.net/2023/04/21/bon…

2/

Max was impossibly glamorous: a perfectly coiffed office manager at Colgate-Palmolive who earned an anthropology degree at CUNY, volunteered at the Brooklyn Zoo, and knew every trick for getting cheap tickets for museums, galleries and shows.

3/

3/

She had an encyclopedic, up-to-the-minute knowledge of all the culture New York had to offer. Staying with cousin Max was fantastic and I went to New York as often as I could.

4/

4/

I went so often I got to know Max's doormen, who not only knew everyone in the building, but also their regular visitors and guests. I'd get off the subway with my suitcase the doorman would greet me by name and hand me the spare keys to 11-J and ask me how my trip had been.

5/

5/

The jobs in the apartment buildings in big northeastern US cities - superintendent, janitor, doorman, gardener, etc - were once union jobs, with benefits and a pension.

6/

6/

Over the years, tenants' associations, homeowners' associations and condo boards switched out these union employees with long-term workers hired in from staffing agencies that promised lower costs.

7/

7/

Now, if you think about it for even a second, it's obvious that there's only one way that hiring a doorman through a staffing agency could be cheaper than just hiring the doorman: the staffing agency has to pay the doorman less.

8/

8/

A *lot* less, because the staffing agency is making money here, too - so the doorman is splitting that lower payment with the agency.

The staffing agencies are *platforms* - just like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Tiktok.

9/

The staffing agencies are *platforms* - just like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Tiktok.

9/

They have end-users (apartment dwellers) and business customers (workers who staff apartments), and they intermediate between them, selling one to the other and making money on both sides.

10/

10/

Like any platform, the staffing agency play is #enshittification: first, making things good for end-users and business-customers, locking both in - and then withdrawing all the surplus from both sides of the two-sided market and pocketing it.

11/

11/

Think of how Uber lost 41 cents on every dollar for more than a decade, until public transit investments had stagnated and yellow cabs had disappeared, allowing the company to double the cost of a ride and halve the compensation for drivers:

pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/alg…

12/

pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/alg…

12/

When it comes to enshittification, digital platforms like Uber had an advantage over analog systems like apartment buildings.

13/

13/

Digital enshittifiers have lots of knobs they can #twiddle, changing the platform rules so fast that buyers and sellers can't develop stable strategies for wrestling some value back. With any shell game, the quickness of the hand deceives the eye:

doctorow.medium.com/twiddler-1b5c9…

14/

doctorow.medium.com/twiddler-1b5c9…

14/

But digital platforms' ability to twiddle merely *improves* enshittification. Digital enshittification is just the usual parasite's game of creating chokepoints between market actors and extract rent from anyone who wants to hire workers - or who wants to work.

15/

15/

Apartment workers who work through staffing agencies have seen declining wages and worsening benefits for years.

16/

16/

That's another way of saying that apartment workers got more from the agencies at the beginning, but as the agencies locked up more apartment buildings and reduced the alternatives for workers, they clawed back their workers' wages and kept it for themselves.

17/

17/

Naturally, this is terrible for morale. It's hard to be a cheerful, deeply knowledgeable doorman, cleaner or super when you can't pay rent. For customers - HOAs, condo boards, tenants' associations - the natural play here would be to cut out the middleman.

18/

18/

They could fire the agency and hire the workers direct.

Except they can't. It turns out that the staffing agencies negotiated secret #NoHireAgreements with the buildings.

19/

Except they can't. It turns out that the staffing agencies negotiated secret #NoHireAgreements with the buildings.

19/

Under these deals, if a building hires any former agency worker, it has to pay the agency a penalty equal to three months' wages for every *other* agency worker in the building.

20/

20/

This keeps low-waged workers locked to the agencies, because the place most likely to make them a better offer is the apartment building where they've worked for years and know intimately, and the employer has to pay a massive fine if they hire the worker direct.

21/

21/

It's no wonder that these workers - and their newly voted-in union, @32BJSEIU - have a blunter name for these "agreements": they call them "#BondageFees."

22/

22/

In an excellent piece for @TheProspect and @workdaymagazine, @sarahlazare describes how these bondage fees are driving the immiseration of a group of workers who once earned a living wage for work that made life easier for people like my cousin Max:

prospect.org/labor/2023-04-…

23/

prospect.org/labor/2023-04-…

23/

Recall that the key to enshittification is #LockIn. Platforms subsidize the arrangement between workers and customers at the start, and then they make it back by squeezing both. The easier it is for either to leave, the less it can squeeze.

24/

24/

The more it hurts workers or customers to leave, the more pain the platform can inflict on both without losing their business.

Economists have a name for the penalties that platforms inflict on disloyal customers and workers: #SwitchingCosts.

25/

Economists have a name for the penalties that platforms inflict on disloyal customers and workers: #SwitchingCosts.

25/

Digital platforms have elevated the inflation of switching costs to a fine art, from Facebook and Twitter holding your friends hostage; to Apple holding your media and apps hostage:

eff.org/deeplinks/2021…

26/

eff.org/deeplinks/2021…

26/

Switching costs are at the heart of the staffing agencies' ripoffs of apartment workers. While the general skills of a building super, cleaner or doorman can transfer well to any jobsite, these workers have incredibly *specific* knowledge of *their* buildings.

27/

27/

The super knows how to fix the balky furnace extractor fan. The cleaner knows just how to reach that awkward corner behind the plant in the lobby. The doorman knows the kid from Toronto whose cousin lives in 11-J.

28/

28/

This means that these workers are especially valuable to the people who live in these buildings, which means that - all things being equal - these workers could bargain for higher wages, especially through their union.

29/

29/

That's why the staffing agencies are so horny for bondage fees, because that's how they make sure that all things are *not* equal.

As Lazare points out, bondage fees are basically just a wrinkle on an existing scam: #NoncompeteAgreements, which bind *one fifth* of the US workforce, prohibiting workers from switching to a competitors' shop.

31/

31/

While noncompetes are lauded as a way of protecting the assets of "knowledge" firms, the vast majority of workers chained to their jobs with noncompetes are low-waged workers in the fast-food sector.

32/

32/

Do we *really* think that there's a major trade secrecy issue in play when a McDonald's cashier switches to a Wendy's down the block for a $0.25/hour raise?

pluralistic.net/2022/02/02/its…

33/

pluralistic.net/2022/02/02/its…

33/

Even in "knowledge" shops, the argument for noncompetes collapses before evidence. Noncompetes are illegal under California's constitution. That means *every single tech company in Silicon Valley* has *always* operated in an environment where workers could fire their bosses.

34/

34/

Indeed, the reason we call Silicon Valley "Silicon Valley" is intrinsically bound to this workers' freedom to change jobs.

35/

35/

The first "silicon" company in Silicon Valley was Shockley Semiconductors, whose founder, William Shockley, got a Nobel prize for helping to invent the silicon transistor.

36/

36/

Shockley was also a delusional racist paranoiac who offered his Nobel money as a bounty to any Black woman who'd get sterilized in the name of "improving the gene pool."

37/

37/

He wasn't just an evil fuck, he was also impossible to work for, wiretapping his employees and even his family members, and creating a chaotic environment that failed to produce the microchips that his transistors promised.

38/

38/

Luckily for everyone who uses anything with a transistor (e.g. everyone), California bans noncompetes. That meant that his eight top employees could quit and start their own company.

39/

39/

You may not have heard of Fairchild Semiconductor, the company that the "traitorous eight" founded, but you've *definitely* heard of the company that two of Fairchild's top employees quit and founded: @intel:

onezero.medium.com/a-the-traitoro…

40/

onezero.medium.com/a-the-traitoro…

40/

If it wasn't for California's guarantee of a worker's right to quit a bad job and get a better one, we might be stuck with "Germanium Valley."

Noncompetes epitomize #MLK's "socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for the poor."

41/

Noncompetes epitomize #MLK's "socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for the poor."

41/

They're a way for employers to operate in a command economy where the power of the state can be mobilized against uppity workers who dare to seek a better deal, and leave workers to sell their labor in a buyer's where the bidders have all the power.

42/

42/

Noncompetes are so manifestly unfair that the @FTC has proposed a nationwide ban on them as an "unfair method of competition":

ftc.gov/news-events/ne…

But, as Lazare points out, bondage fees are just noncompetes by another name.

43/

ftc.gov/news-events/ne…

But, as Lazare points out, bondage fees are just noncompetes by another name.

43/

The major player in bondage fees is (ironically) a Toronto-based company called #FirstService, who operate through their subsidiary @PlannedTeam to enshittify apartment buildings on a massive scale.

44/

44/

The workers organized by SEIU 32BJ have filed a complaint against Planned over these bondage fees:

seiu32bj.org/wp-content/upl…

45/

seiu32bj.org/wp-content/upl…

45/

Planned employs nearly half of the doormen and conceirges in the northeast; that's called a "#monopsony." Monopsonies are the less-well-known twin brothers of #monopolies, markets in which *buyers* (rather than sellers) have power.

46/

46/

Monoposony may be an obscure concept - unlike "monopoly," there's no family-destroying board-game to get us familiarized with the term.

47/

47/

But monopsonies are just as toxic as monopolies, especially for workers, where an employer's ability to restrict the places where you can sell your labor can force workers into dangerous, miserable conditions.

48/

48/

Maybe if Tennessee Ernie Ford had figured out how to rhyme "company store" with "monopsony," we'd be more alive to this danger:

genius.com/Tennessee-erni…

49/

genius.com/Tennessee-erni…

49/

Though Pearson's workers organized under SEIU in 2019, they still don't have a contract. Among their top demands: an end to bondage fees.

50/

50/

The staffing agencies say these fees are necessary to recoup the costs "associated with recruiting and referring temporary workers." But we're talking about workers with years - *decades* - of experience. Those costs were recouped many times over:

go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GAL…

51/

go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GAL…

51/

Bondage fees are closely held secrets. Planned's workers can hold their jobs for years without knowing of their existence. But the *Prospect* got ahold of some of these secret agreements, finding one- and two-year noncompete clauses hidden in them.

52/

52/

As more Planned/Firstservice workers try to form unions, the company has begun illegally firing the organizers, like Kevin Borowske.

53/

53/

Borowske was a live-in caretaker at Minneapolis's Centre Village, and when Firstservice fired him for trying to start a union, he didn't just lose his job, he lost his home, too.

54/

54/

For bosses using bondage fees to lock in workers, secrecy is vital. Without a record of where these agreements exist and their specifics, it's hard for state and fed enforcers to fight them There's no better way to drag these dirty secrets into public than through unions.

55/

55/

Image:

crystalsquare apts (modified)

flickr.com/photos/1261703…

CC BY-SA

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa…

eof/

crystalsquare apts (modified)

flickr.com/photos/1261703…

CC BY-SA

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa…

eof/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter