With our new paper just out thought I'd write a brief thread about one of the ways avian influenza virus ('bird flu') adapts to mammals (with a focus on the polymerase).

Will aim to start off simple then get into the weeds!

journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jv…

Will aim to start off simple then get into the weeds!

journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jv…

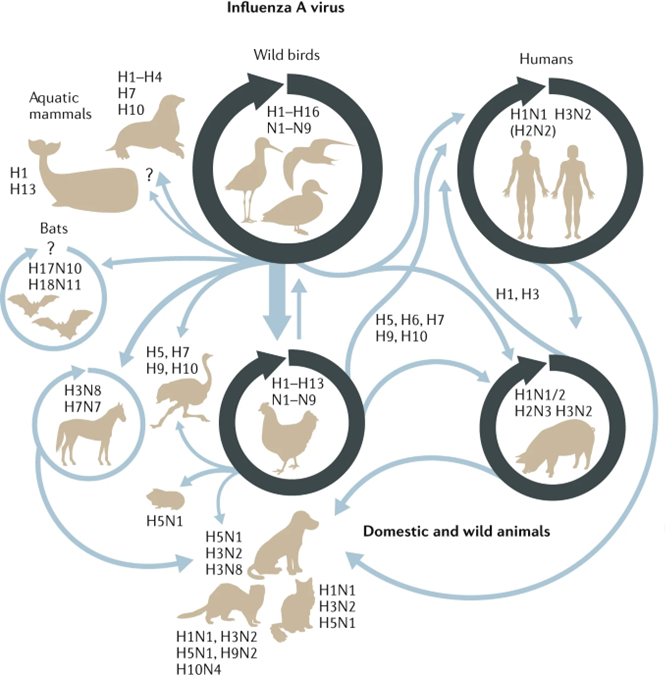

The natural host of influenza viruses is wild aquatic birds - ducks, geese, gulls, etc.

Flu is very good at jumping into other species, including mammals like pigs, dogs, horses, and of course humans.

Flu is very good at jumping into other species, including mammals like pigs, dogs, horses, and of course humans.

Avian influenza cannot generally infect and replicate within mammals very efficiently. Because flu is an RNA virus and mutates very fast, it can quickly pick up adaptations. Sometimes these adaptations are enough to even transmit between mammals.

Although theres a lot we dont understand - we have a good handle on what some of these mutations are, what they do, and why the virus needs them - great article by @kakape here summerising some of the best known adaptations -

https://twitter.com/kakape/status/1643993203799113730

One area which the lab of @wendybarclay11 (where I did one of my postdocs) is particularly interested in is adaptation of the influenza polymerase.

The flu polymerase is responsible for making copies of the viruses RNA genome during virus replication.

The flu polymerase is responsible for making copies of the viruses RNA genome during virus replication.

Influenza is a fairly simple virus - its genome is less than half the size of a coronavirus genome and and 10x smaller than a herpesvirus genome.

To efficiently copy its genome flu therefore takes maximum advantage of the machinery of the cell it has infected.

To efficiently copy its genome flu therefore takes maximum advantage of the machinery of the cell it has infected.

However, many of these 'host factors' can vary between a bird and a mammal. This can explain why theres sometimes a block to infection in a new host - the factors the virus likes to hijack are wrong (or even missing entirely).

This is true of many viruses.

This is true of many viruses.

Avian influenza had long been known to have a problem with its polymerase in mammalian cells - the virus just isnt able to replicate its genome efficiently.

This had been mapped to a single mutation in one of the units of the influenza polymerase (called PB2 E627K)

This had been mapped to a single mutation in one of the units of the influenza polymerase (called PB2 E627K)

The lab of @wendybarclay11 went a step further and identified the exact 'host factor' that was different between birds and mammals that resulted in this. A family of proteins called 'ANP32'.

nature.com/articles/natur…

nature.com/articles/natur…

Specifically birds generally express a longer version of ANP32A which avian influenza can use really well. During adaptation to mammals avian flu has to get PB2-E627K in order to use the shorter version of this protein.

This discovery explained a lot of interesting observations about flu - eg, unlike other birds, ostriches and emus only express the 'short version' so are prone to getting the mammalian-like adaptation PB2-E627K (another good reason not to hug a sick emu!) doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01…

So what does ANP32A actually do?

Well... its pretty complicated and we're still learning but its probably regulating the different types of replication flu polymerase can do, and maybe helping properly assemble new infectious genomes doi.org/10.1038/s41586…

Well... its pretty complicated and we're still learning but its probably regulating the different types of replication flu polymerase can do, and maybe helping properly assemble new infectious genomes doi.org/10.1038/s41586…

So now a little more into the weeds...

PB2-E627K is not the only mammalian adaptation in PB2 seen. the 2009 pandemic is missing it entirely and instead has different mutations.

In fact many PB2 mutations are known to also adapt to mammals

PB2-E627K is not the only mammalian adaptation in PB2 seen. the 2009 pandemic is missing it entirely and instead has different mutations.

In fact many PB2 mutations are known to also adapt to mammals

For example, you may remember recent reports of the H5N1 outbreak on a Spanish mink farm - these did not get E627K, but instead got T271A (which was one of the mutations the 2009 pandemic had). Additionally many human infections result in Q591R/K (also in pandemic 2009) or D701N.

So if E627K specifically adapts the polymerase to use the shorter mammalian ANP32A proteins, what do these other mutations do?

Do they do the same thing or something different?

We aimed to answer this question.

Do they do the same thing or something different?

We aimed to answer this question.

Using human or chicken cell lines where ANP32A (+ANP32B in human cells). We saw that (in our hands at least) both Q591R and D701N also appeared to specifically adapt the polymerase to use the short mammalian ANP32 proteins.

T271A, on the other hand, didnt appear to do this.

T271A, on the other hand, didnt appear to do this.

Whats more we thought we could see an interesting pattern... although in birds only ANP32A can support flu polymerase, in most mammalian species both ANP32A and ANP32B can support it (to some degree)

We saw a bias in preference for mammalian ANP32A vs ANP32B - while E627K really liked ANP32B, D701N (the other most common adaptation) prefered ANP32A proteins.

This was interesting, as lots of mammals have an ANP32 protein that is 'better' at supporting flu - in mice and humans in ANP32A - in most other mammals its ANP32B

We hypothesised this might explain why E627K is so very common in human cases, and lab mouse experiments, but comparatively rarer in other mammalian infections.

To explore this further we took avian influenza viruses (that had had most of thier genes replaced with those from an attenuated lab strain to make them safer to use) and looked how they adapated to human cells missing ANP32A or ANP32B.

We found that while virus quickly picked up E627K in cells expressing ANP32B (control and ANP32A knock out cells). No E627K was detectible when we knocked ANP32B - suggesting E627K is specifically an adaptation biased towards this ANP32 protein.

What does this mean? Well it might suggest that mammalian adapted viruses might still not be optimally adapted to infect humans (and therefore still have a host barrier). Clearly this isnt too major as in 2009 the swine influenza virus than caused the pandemic didnt have E627K...

I should say as well that viral genetics clearly plays a huge role in this - some avian influenza viruses are incompatable with E627K. Its all pretty complex!

doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01…

doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01…

We started this work pre-pandemic (and I errr got a little distracted), but in that time we now have structures of the influenza polymerase/ANP32 complex.

E627K, Q591R/K and D701N all sit fairly close to one another so this makes a lot of sense! doi.org/10.1038/s41586…

E627K, Q591R/K and D701N all sit fairly close to one another so this makes a lot of sense! doi.org/10.1038/s41586…

with that I just want to thank the Barclay lab and all co-authors for thier help, particularly @Dr_Shepp and Maragaret Lister for helping get this over the line!

For more info highly recommend this review (which I took lots of figures from for the thread) nature.com/articles/s4157…

For more info highly recommend this review (which I took lots of figures from for the thread) nature.com/articles/s4157…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh