Excited to have @mpiccininni3 speaking at the @turinginst causal inference interest group about whether cognitive screening tests should be corrected for age and education

#CIIG #EpiTwitter #CausalTwitter

#CIIG #EpiTwitter #CausalTwitter

Marco explains it is fairly standard, when performing cognitive screening tests, to 'correct' (or standardise) the result for demographic characteristics (e.g. age and level of education). The resulting score tells you someone's result for people of similar age & education

'Correcting' the cognitive score for age and education is therefore equivalent to ignoring the part of the cognitive test score that is due to age and education.

So an older (or less educated) person needs to score lower on the raw test to achieve the same 'corrected' result.

So an older (or less educated) person needs to score lower on the raw test to achieve the same 'corrected' result.

One philosophical argument in favour of 'correcting' for age is that cognitive performance naturally declines with age. But for a screening test, we're interested in detecting pathology, not aging. There isn't however a similar argument for correcting for education!

Statistically, correcting for age and education is also thought to improve the accuracy of the screening test by removing variability in the test. However, in practice, the corrected scores appear to perform worse than uncorrected scores.

The reason: age and education don't just contribute to variability in the screening test, they also influence the probability of the impairment that we are interested in detecting. So 'correcting' for them removes information about the impairment we are trying to predict.

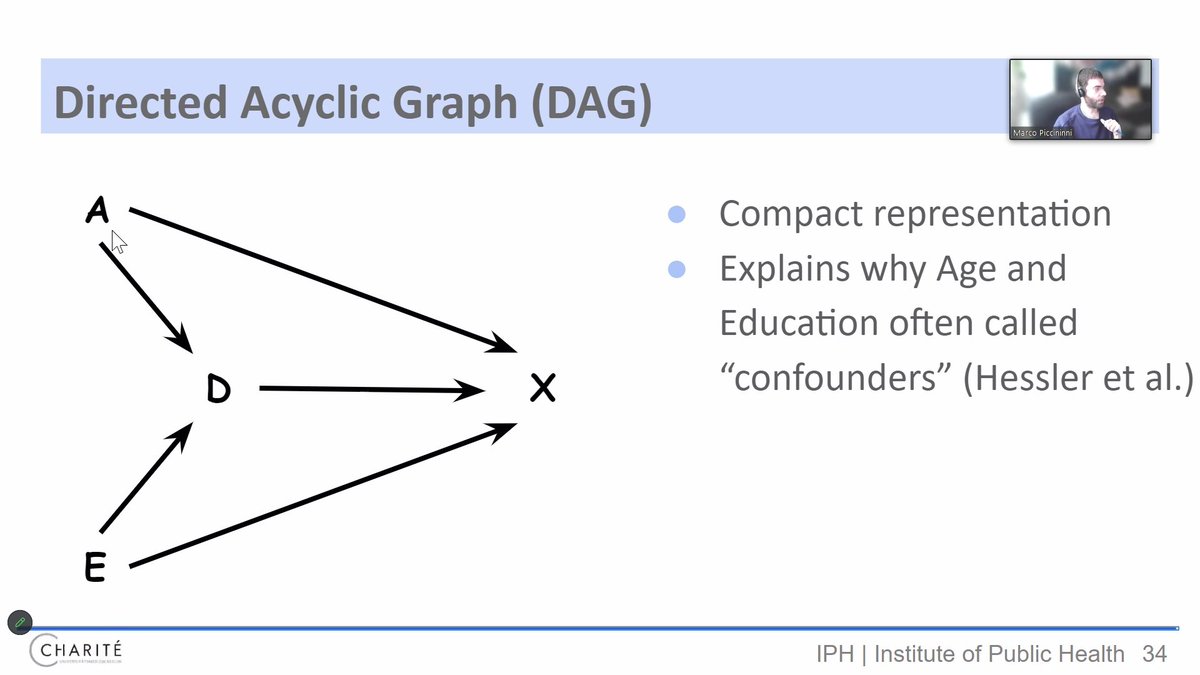

Marco explains that this apparent 'paradox' can be understood with a causal perspective. 'Like all good projects, we start with a directed acyclic graph'.

Within a DAG, we can see that when you correct for age and education, you block two key causes of both the cognitive screening tool and the level of cognitive impairment. This hence leads to lower discriminating performance.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh