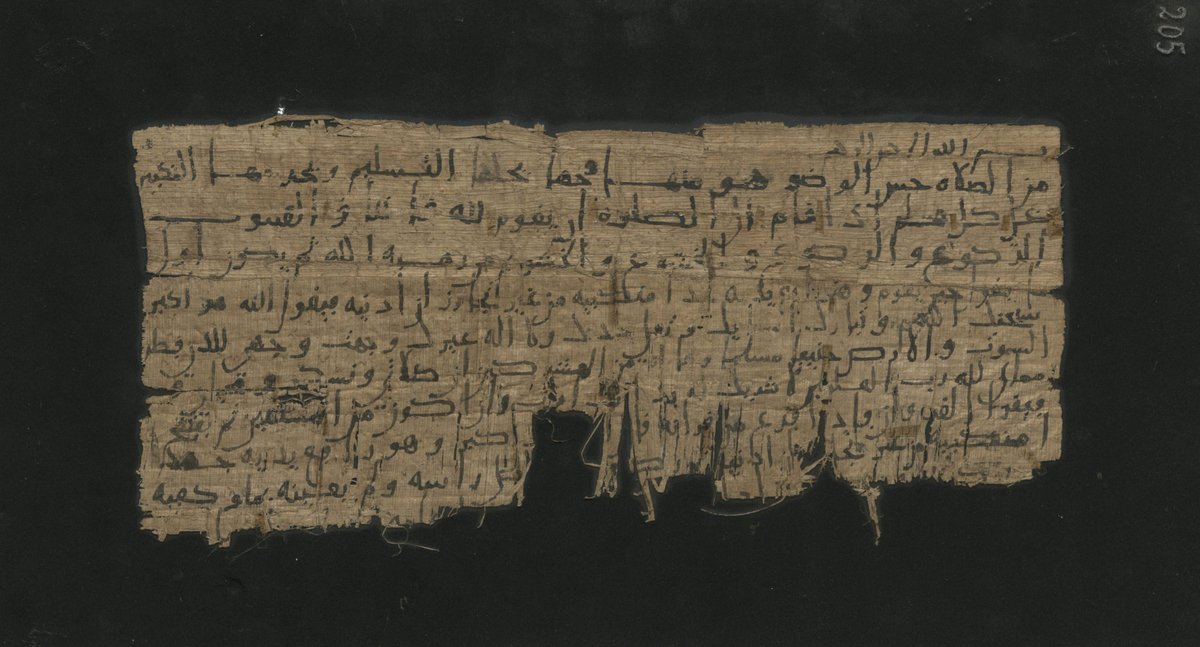

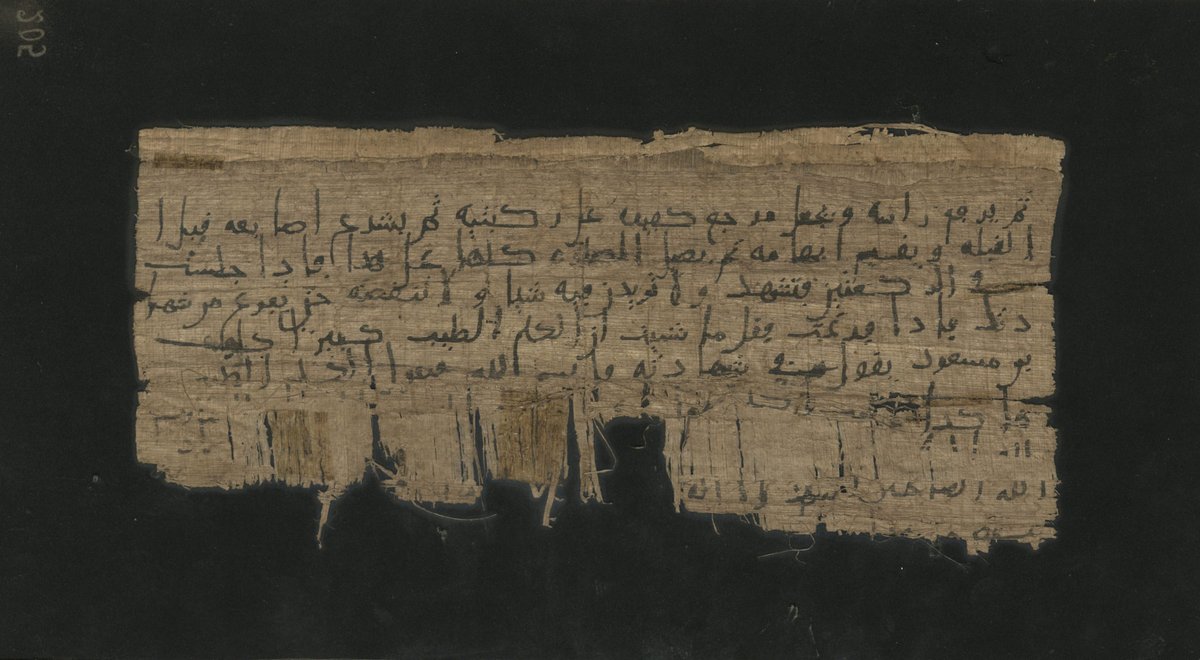

A late-Umayyad writing inscribed on the walls of Khālid al-Qasrī Palace ("Kharāʼib askāf Banī Junayd") in Iraq.

The text is quite rare as it lists the names of the companions who were promised paradise in Sunni Islam.

The text is quite rare as it lists the names of the companions who were promised paradise in Sunni Islam.

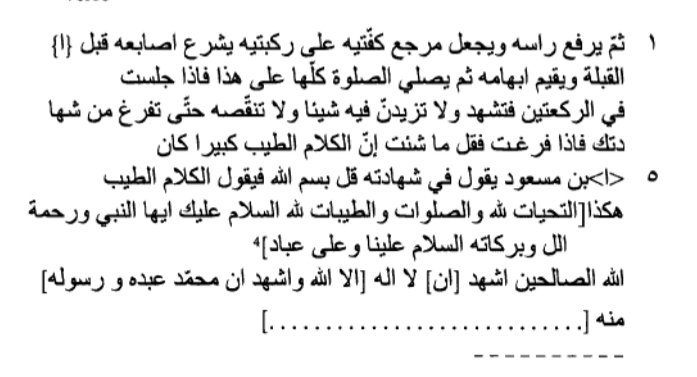

Translation: "May God forgive Abū Bakr and ʻUmar and ʻUthmā<n> and ʻAlī and Ṭalḥa and Zub<ay>r and Saʻd and Saʻīd and ʻAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʻAwf al-Zuh<ry> and Muʿ<ā>wiya ibn Abī Sufyān."

Notice the exclusion of Abū ‘Ubaydah for Muʿāwiya. In Sunni tradition, Muʿāwiya was never personally promised paradise.

Source: Treasures of the Iraq Museum = Kunūz al-Matḥaf al-ʻIrāqī. Ministry of Information Directorate General of Antiquities 1976.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter