“Income-Based Affirmative Action in College Admissions” is online at the Economic Journal’s site! In this project w/@_Herskovic and @joaoramosecon,we show that income-based affirmative action in college admissions can increase welfare and efficiency simultaneously.🧵#EconTwitter

https://twitter.com/EJ_RES/status/1651251380558897153

Student-level microdata from Brazil show that high-income students outperform low-income students with similar demographic characteristics. This pattern is weakened but still holds if one compares students in the same classroom.

However, this relation is reversed after controlling for college-admission scores: low-income students outperform their higher-income peers in college when they have the same college-admission score.

A student from an underprivileged background with the same admission score as a high-income peer has positive unobserved characteristics that allow her to attain a higher college return.

This empirical finding suggests that efficiency gains can be obtained if college admissions favor low-income applicants because such a policy would substitute low-income students for high-income students with similar admission scores.

We develop a structural model designed to speak to this empirical finding. The fundamental element is that investments in pre-college education differentially affect admission scores and human capital.

High-income families make large pre-college investments, strongly affecting their child’s admission scores and crowding-out low-income students from college education. These investments, however, don’t translate into human capital gains by the same proportion as admission scores.

This fact generates an inefficient college admission environment, making room for income-based affirmative action (AA) policies to be efficiency-enhancing.

We calibrate the model to fit educational and labor market data from Brazil, where AA policies in college admissions are widely implemented.

At the calibrated parameters, aggregate output and social welfare increase when the AA policy reallocates some public college seats from high-income to low-income students.

However, lower educational investments from the non-preferentially-treated students is an equilibrium backlash of the policy, resulting in lower aggregate output as policy intensity increases.

We compute two optimal income-based AA policies: one that maximizes aggregate output (efficiency maximizing) and one that maximizes social welfare. Both policies reallocate public college seats from high-income to low-income students.

The efficiency-maximizing policy increases aggregate output by 0.23%. To interpret this magnitude, note that access to public college spots is limited, with only 4.8% of 18- to 36-year individuals having a public college degree.

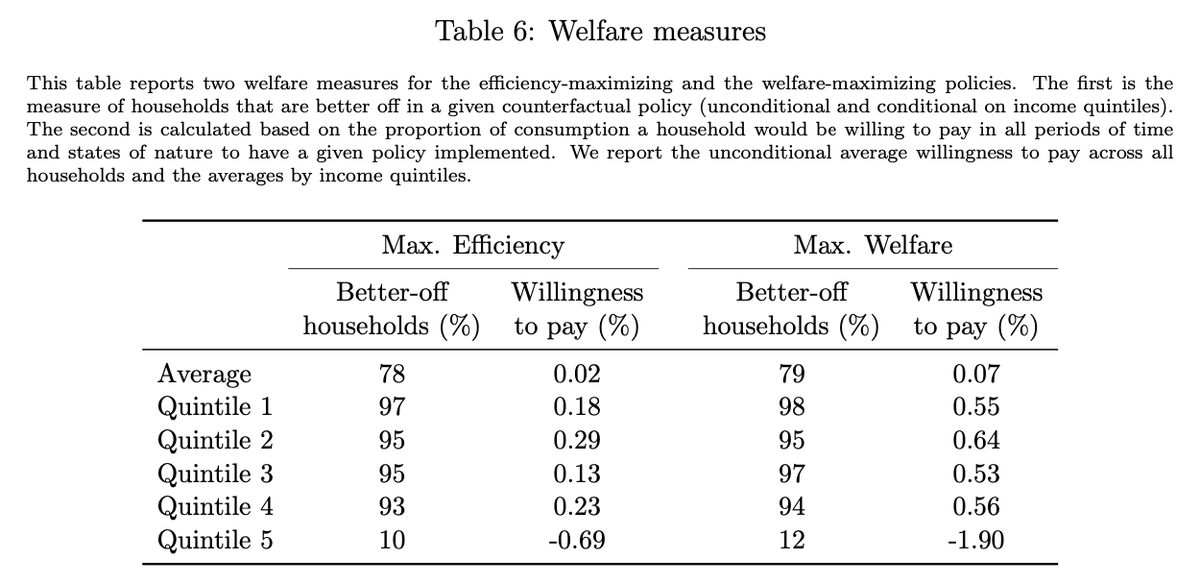

The welfare-maximizing policy benefits nearly 80% of the families, generating considerable welfare gains as gauged by a willingness to pay measure.

However, households in the top income quintile are harmed: on average, they would need to receive 1.9% of their consumption in all periods and contingencies of the policy equilibrium to be compensated for their losses.

AA policies in college admissions can generate significant welfare gains. Why are they so controversial? Our results shed light on this apparent paradox from two different angles.

First, high-income families might be severely harmed, which might pose challenges when trying to pass such policies through the political process.

Second, the design of an AA policy is complicated, and, as a result, a sub-optimal policy may be implemented. For example, our analysis shows that even though the policy implemented in Brazil benefitted a large majority of the population, it still can be improved.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter