I receive a nice suggestion to do a series of short thread about the "Arabic letter of the Week". Let's see if I can say something interesting and unexpected about all the letters of the Arabic alphabet! Starting today with the ʾalif.

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

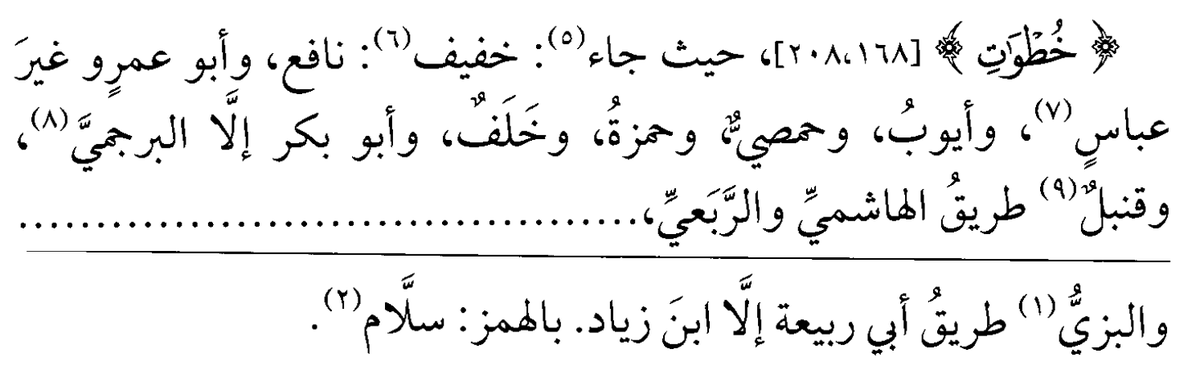

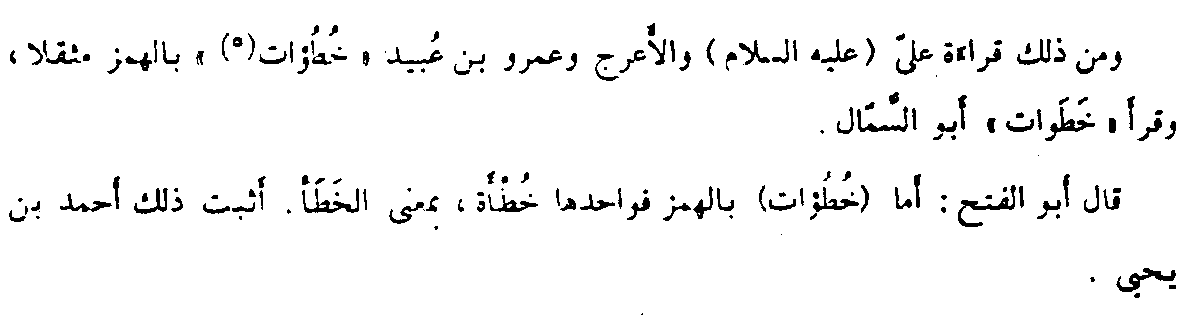

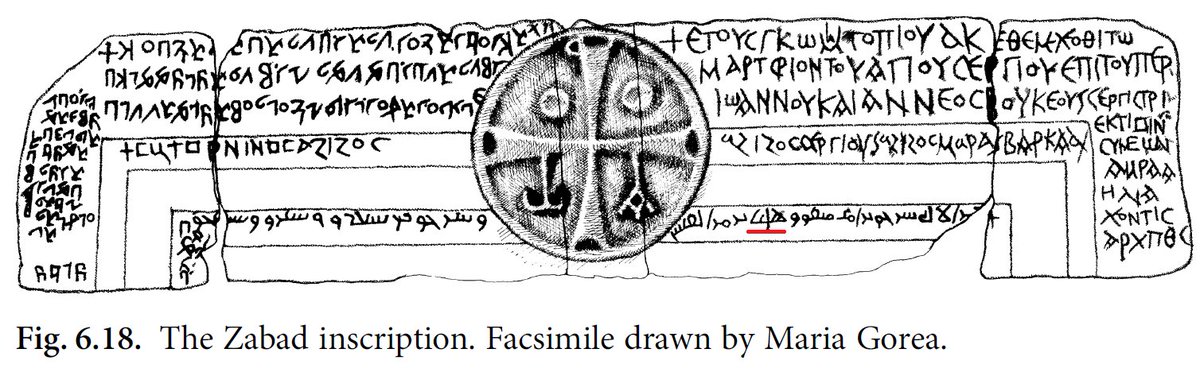

In Pre-Islamic Arabic the letter ʾalif was used to write the hamzah, even in places where Classical Orthography would expect a different seat of the hamzah.

A name like hunayʾ would be spelled هنيا. The modern spelling is due to the loss of Hamzah in Hijazi/Quranic Arabic.

A name like hunayʾ would be spelled هنيا. The modern spelling is due to the loss of Hamzah in Hijazi/Quranic Arabic.

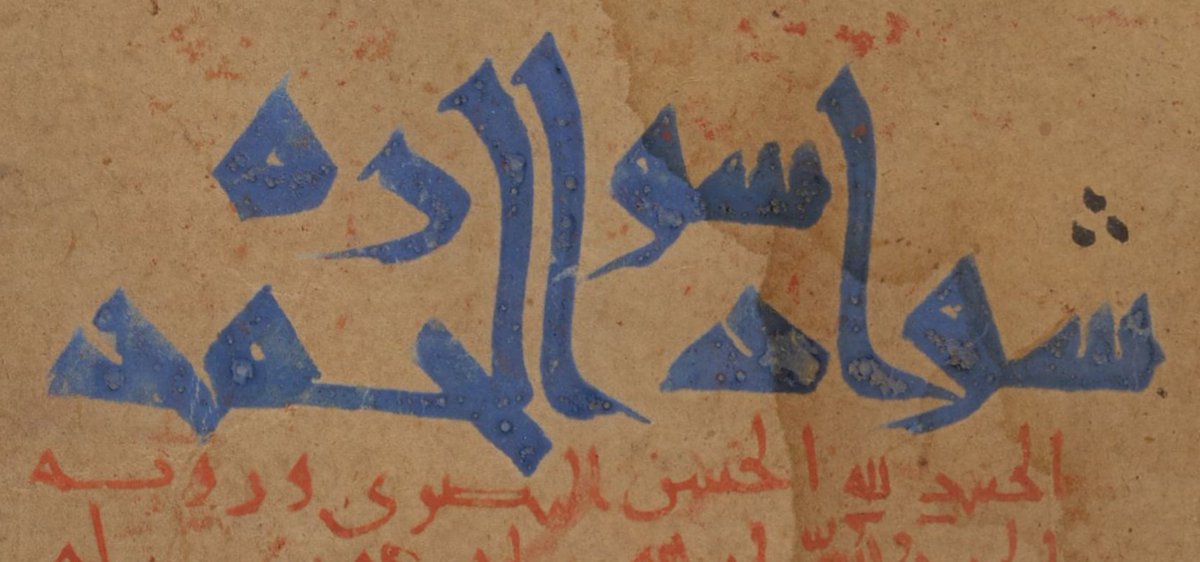

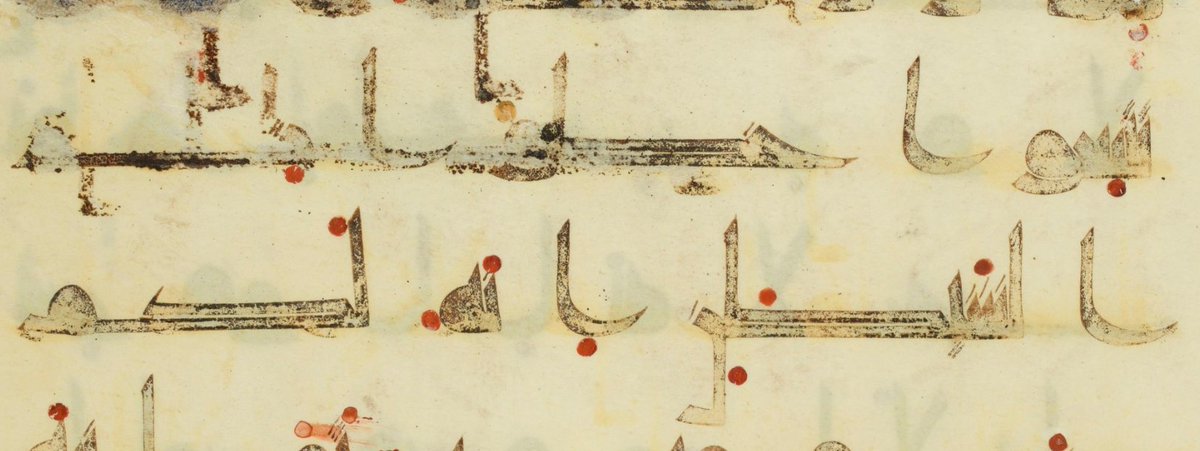

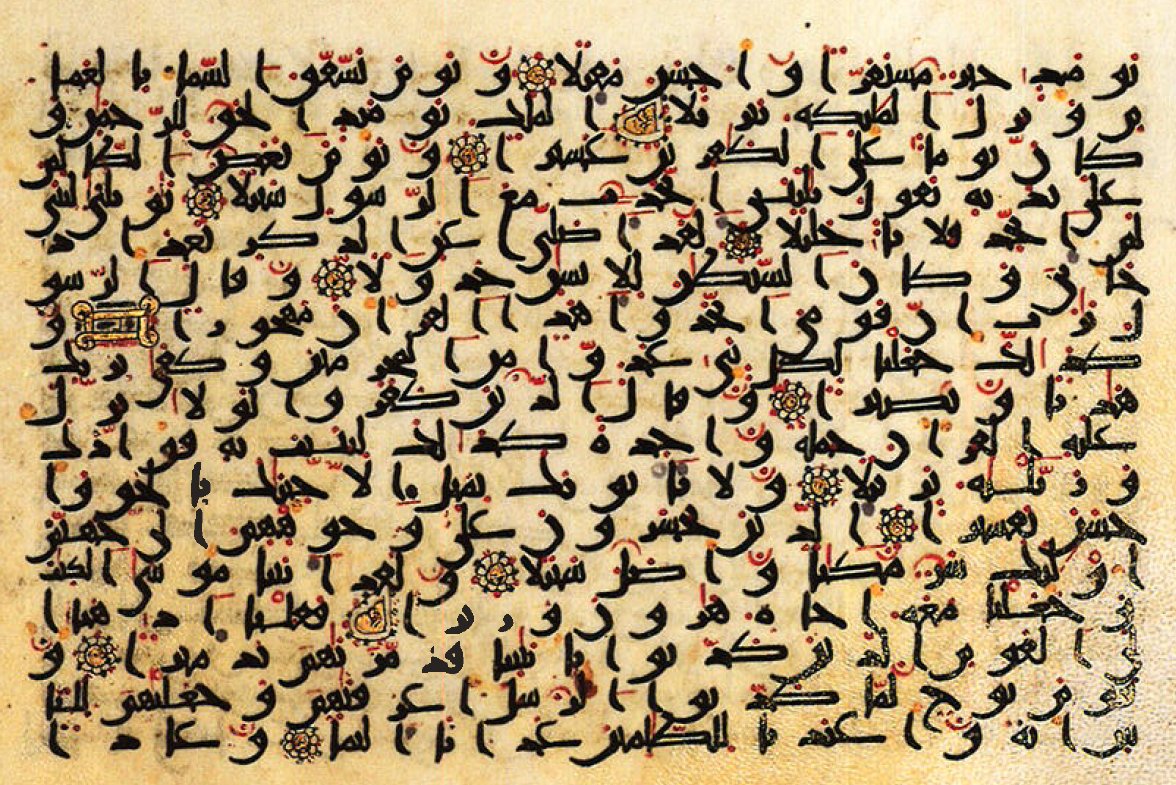

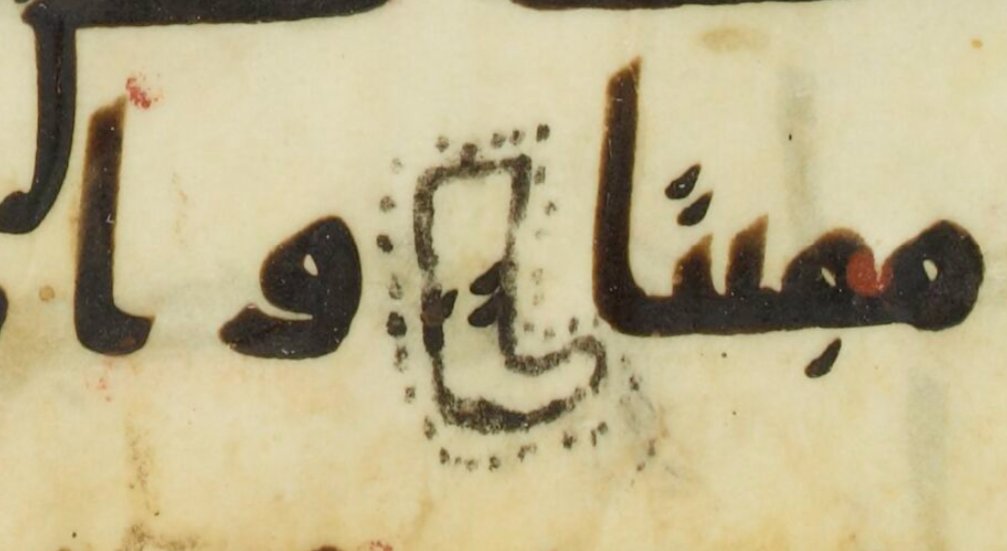

In Early Quranic manuscripts, an outlined ʾalif, usually filled in with a bisected two-tone colour, is used to mark every fifth verse as a 5-verse marker. Presumably it's the ʾalif of ʾāyah آية.

1. Leiden Or. 14.545a

2. BnF Arabe 330b

1. Leiden Or. 14.545a

2. BnF Arabe 330b

I'll leave it at that as a thread for now! Thanks to @jabunna for this fun idea. :-)

https://twitter.com/jabunna/status/1654518587804065794

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter