#HistoryKeThread: Elijah Masinde

——-

Over the years, even way before ill-famed Pastor Paul Mackenzie became known, Bungoma has been synonymous with prophets and gods - Nabii Yohana, Yesu wa Tongaren, Jehovah Wanyonyi and Elijah Masinde among them.

——-

Over the years, even way before ill-famed Pastor Paul Mackenzie became known, Bungoma has been synonymous with prophets and gods - Nabii Yohana, Yesu wa Tongaren, Jehovah Wanyonyi and Elijah Masinde among them.

Let us focus on Elijah Masinde, who broke out earlier than the rest.

In his early years, he was employed as a court server, working at the Kabuchai African Court in 1937.

In his early years, he was employed as a court server, working at the Kabuchai African Court in 1937.

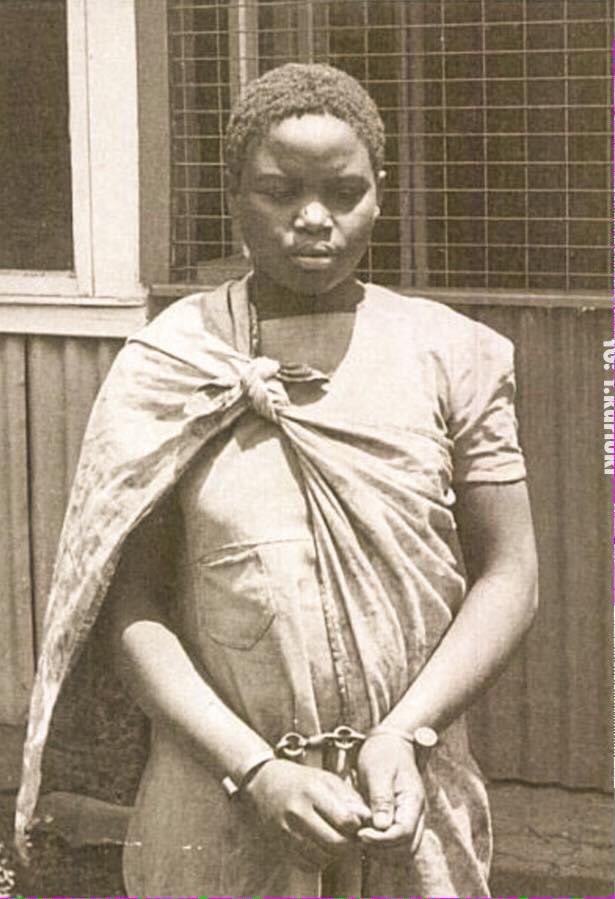

Masinde (pictured) did not like many things. For example, he hated the fact that his duties included arresting suspects and attaching their property.

One morning, in front of the local District Commissioner, he threw down his uniform outside the Kabuchai African Court and told him “I am returning your uniform. I do not need it. I am no longer your servant”.

He then walked away, never to be seen in the court precincts again.

Years later, in the early 1940s, he started a campaign against the conscription of Africans to fight in World War II. It was around this time that he formed the Dini ya Musambwa sect.

Years later, in the early 1940s, he started a campaign against the conscription of Africans to fight in World War II. It was around this time that he formed the Dini ya Musambwa sect.

Initially, there was controversy about who actually formed the sect. A Mzee Walumoli claimed that it was actually him who received word from Wele (God), and that he subsequently recruited Masinde because the former process server was bold, popular and eloquent.

Whereas the latter-day Pastor Mackenzie was, according to media reports, against modern education, Masinde preached openly against the colonial administration and Christianity.

Masinde also had a violent streak. On at least one occasion, he stood trial for assaulting a chief in western Kenya in 1944.

The assault happened after Masinde had addressed a baraza at Kimilili, where he called on Europeans and members of the Asian community to leave Kenya.

The assault happened after Masinde had addressed a baraza at Kimilili, where he called on Europeans and members of the Asian community to leave Kenya.

“They have to leave everything they own behind because they did not come with anything from their country”, he said.

Matters came to a head when Masinde addressed another baraza that was - in the estimation of administration officials, attended by 5,000 followers.

Matters came to a head when Masinde addressed another baraza that was - in the estimation of administration officials, attended by 5,000 followers.

At the baraza, Masinde announced that he had unearthed the white man’s oathing secrets and scattered them into the four corners of the world. By that act, Masinde argued, the white man had lost the power to oppress Africans.

This news was well received by locals. Masinde’s popularity grew.

Colonial officials panicked.

Colonial officials panicked.

When word went round that Masinde was facing arrest, he went into hiding in the forests of Mt. Elgon. At Malakisi, hundreds of Dini ya Musambwa faithfuls and Bukusus congregated to stage protests in support of Masinde and his Dini ya Musambwa.

By that time his sect had spread to East and West Pokot, as well as to various parts of eastern Uganda.

At Malakisi, police moved in to quell the protests. In the aftermath, many protestors were shot dead. Police gave the number of dead as 11, although locals claimed that the number of fatalities was higher.

Masinde remained in hiding until 1948, when he turned himself in, aged 38. In February of the same year, the colonial administration declared the sect illegal.

He was consequently charged with sedition and deported to Lamu prison to serve his sentence.

He was consequently charged with sedition and deported to Lamu prison to serve his sentence.

It was not until 1961 when he was released from prison alongside other leading political lights like Jomo Kenyatta, Paul Ngei, Kung’u Karumba, Achieng Oneko and others.

Elijah Masinde’s involvement in politics was minimal in the post-independence period. Although he joined KANU on the urging of his namesake, politician Masinde Muliro, he generally lived a quiet life until his death in Bungoma in 1987.

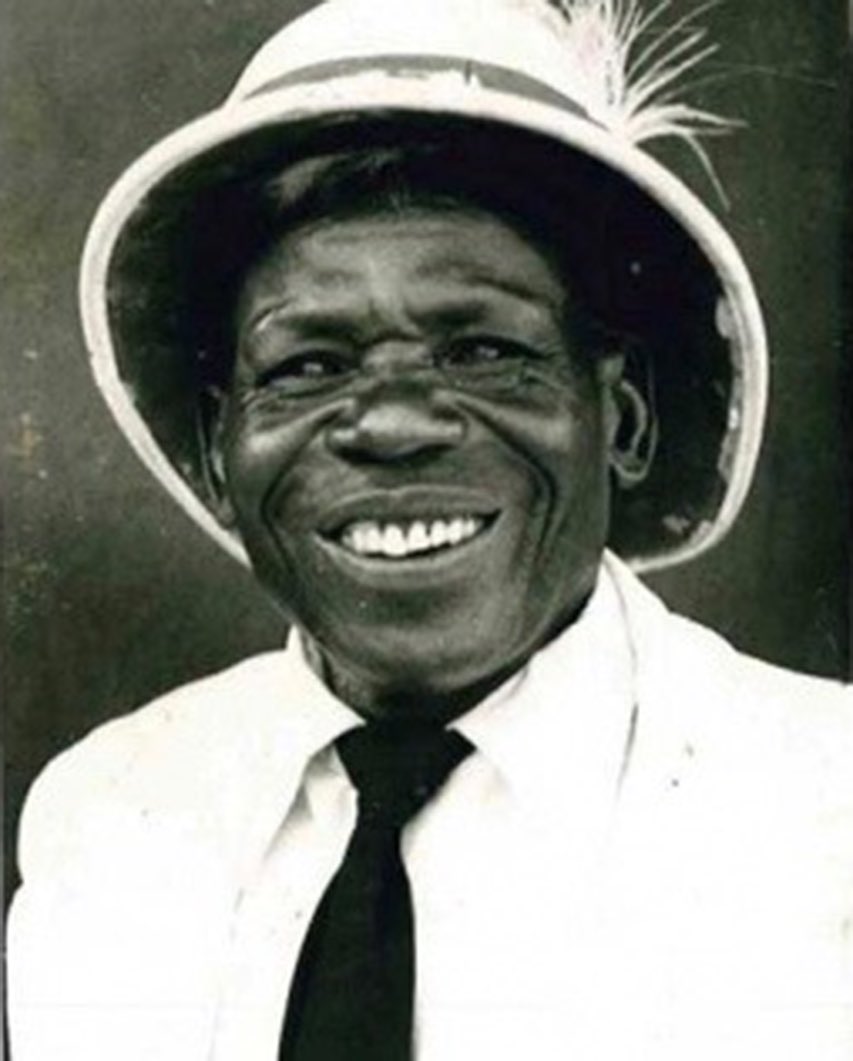

In this 1975 photo (credits), Elijah Masinde confers with his lawyer outside a court in Kitale. Successive post-independent governments did not tolerate the Dini ya Musambwa sect and upheld its proscription.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter