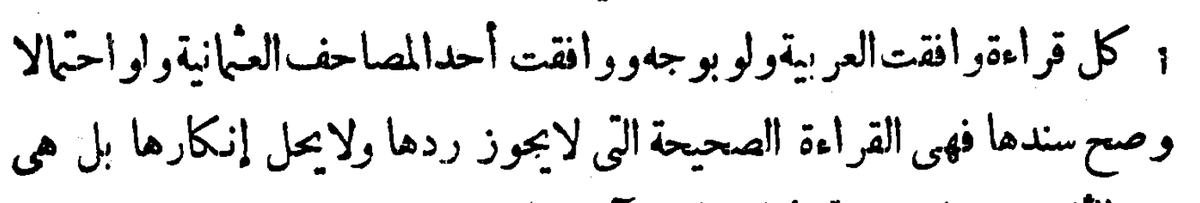

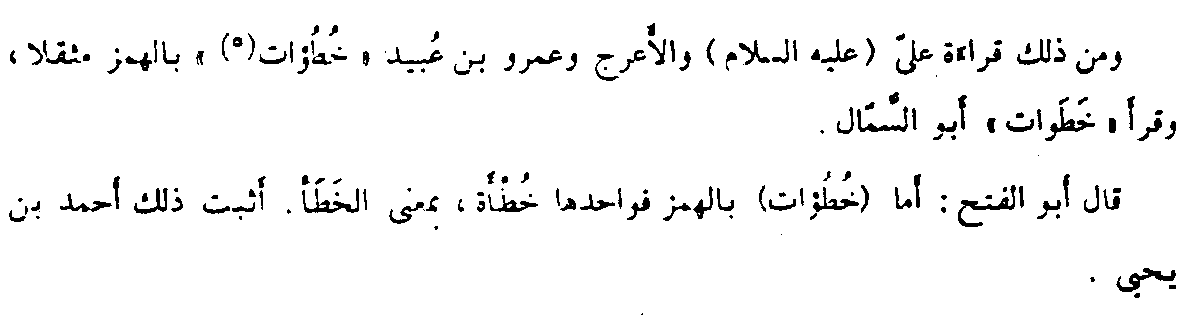

In the modern Arabic script the letter tāʾ and bāʾ have the exact same letter shape. This is true for the Arabic script in all Islamic era documents.

But this was not always the case! While bāʾ & tāʾ merge, they were at one point distinct!

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

But this was not always the case! While bāʾ & tāʾ merge, they were at one point distinct!

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

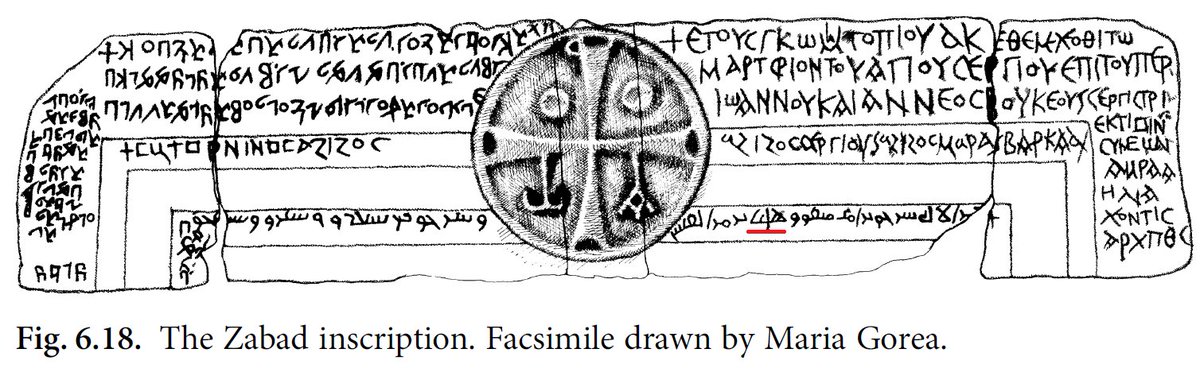

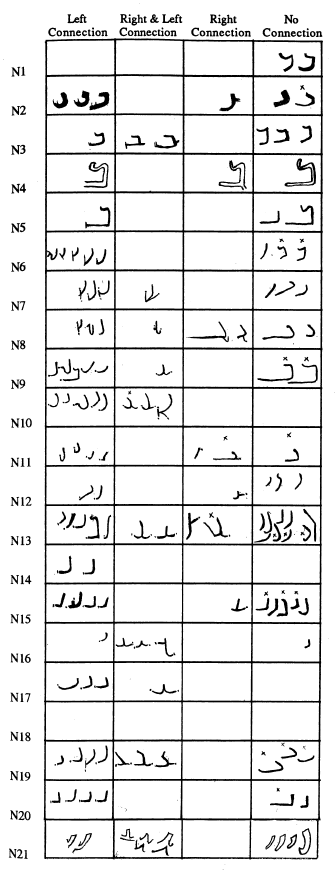

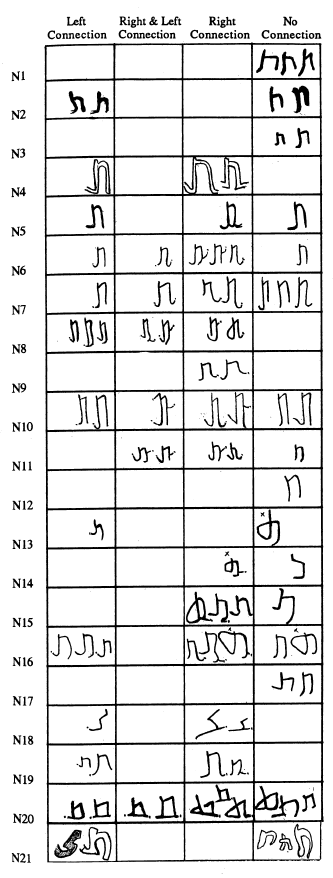

In the Nabataean Aramaic script, the <b> and <t> had very distinct signs, quite similar to the shapes we find in the Hebrew script: ב and ת.

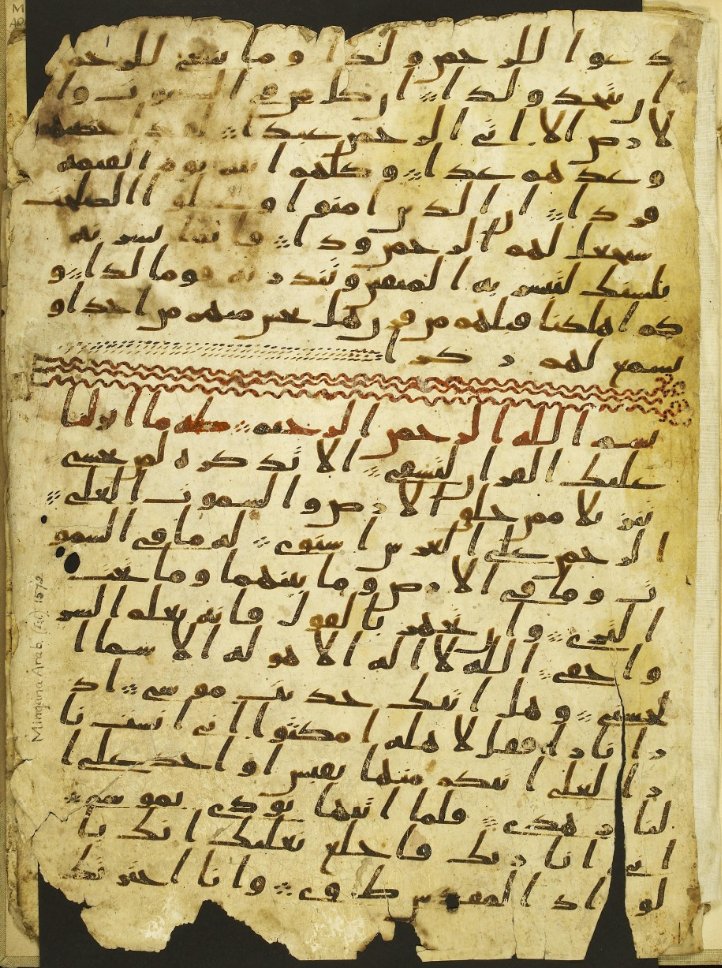

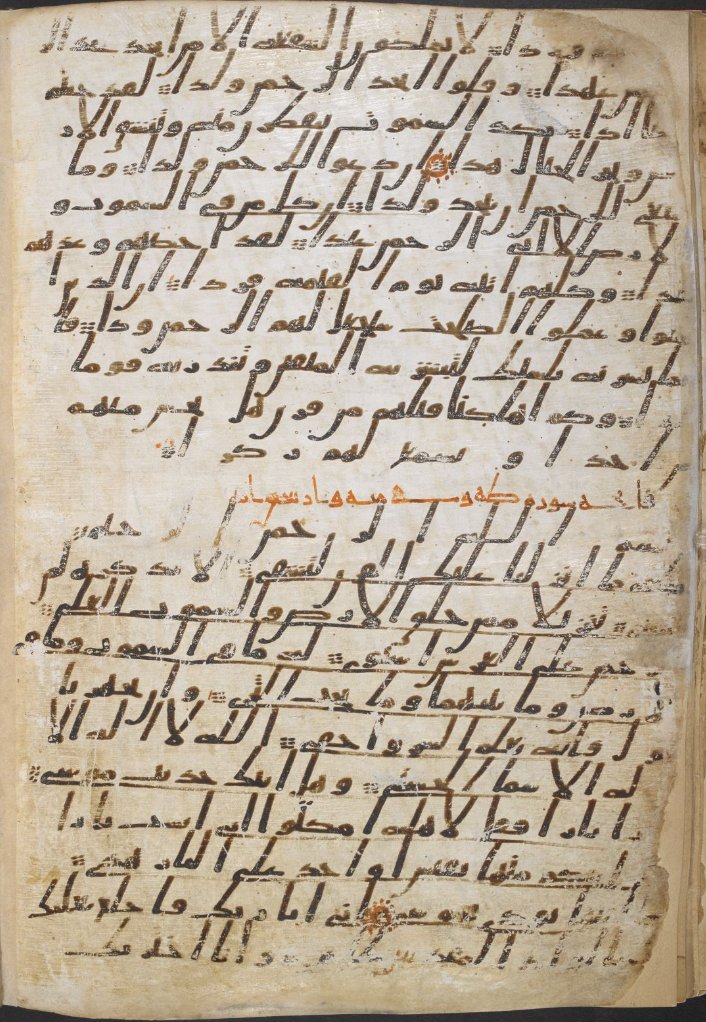

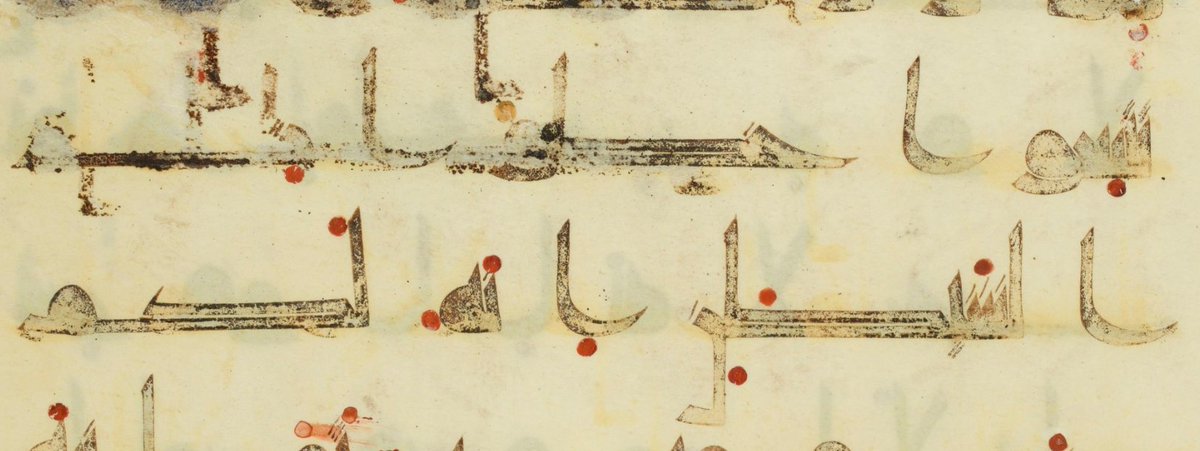

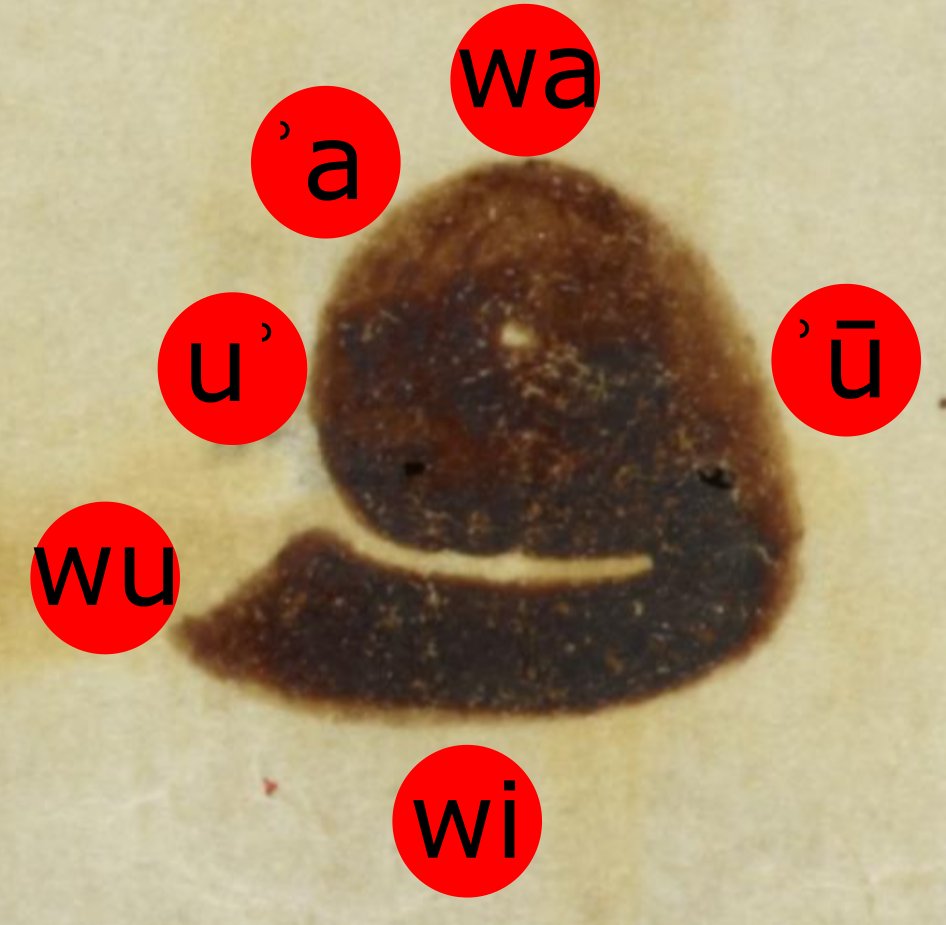

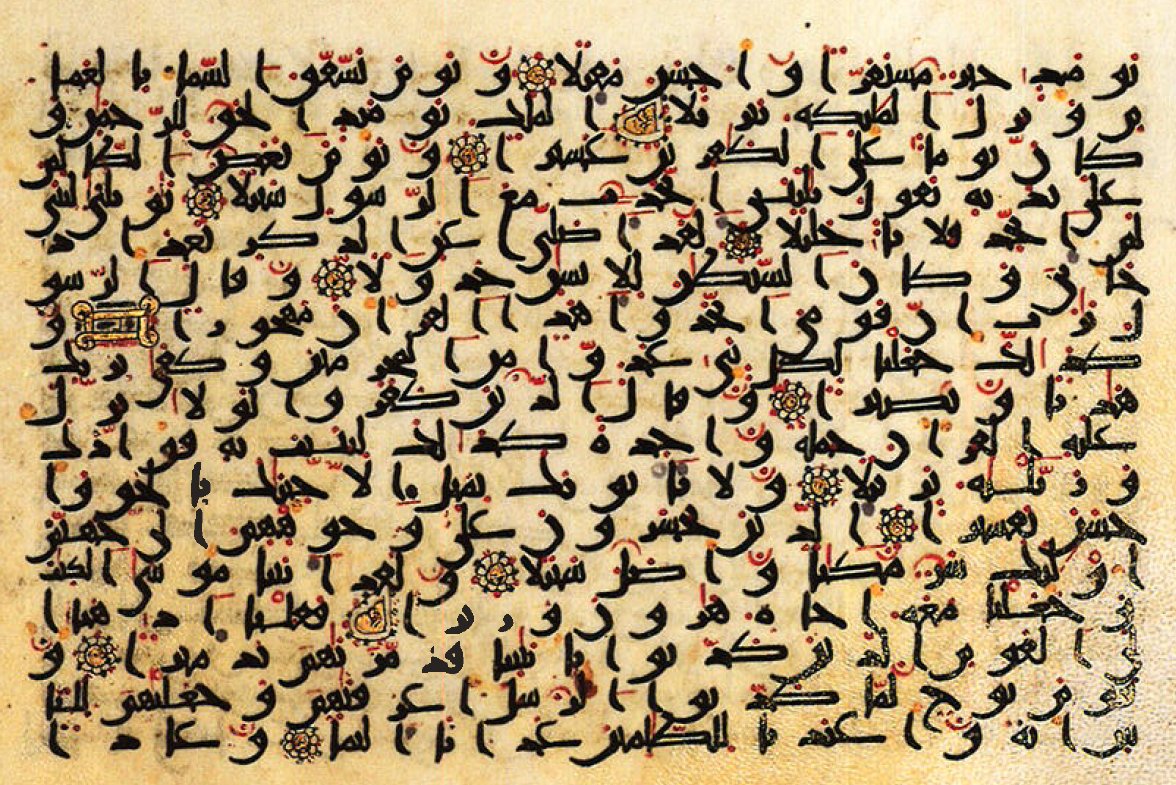

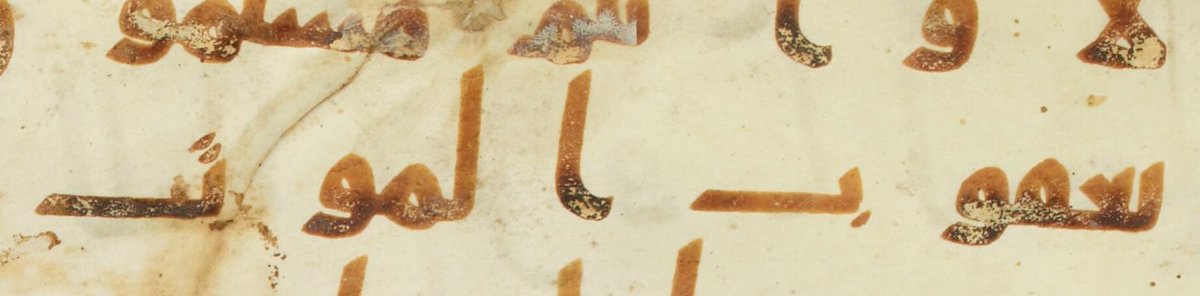

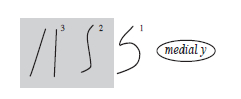

The bāʾ takes on the simple hook + horizontal stroke quite early on, but the tāʾ continues to have a distinct two downward strokes.

The bāʾ takes on the simple hook + horizontal stroke quite early on, but the tāʾ continues to have a distinct two downward strokes.

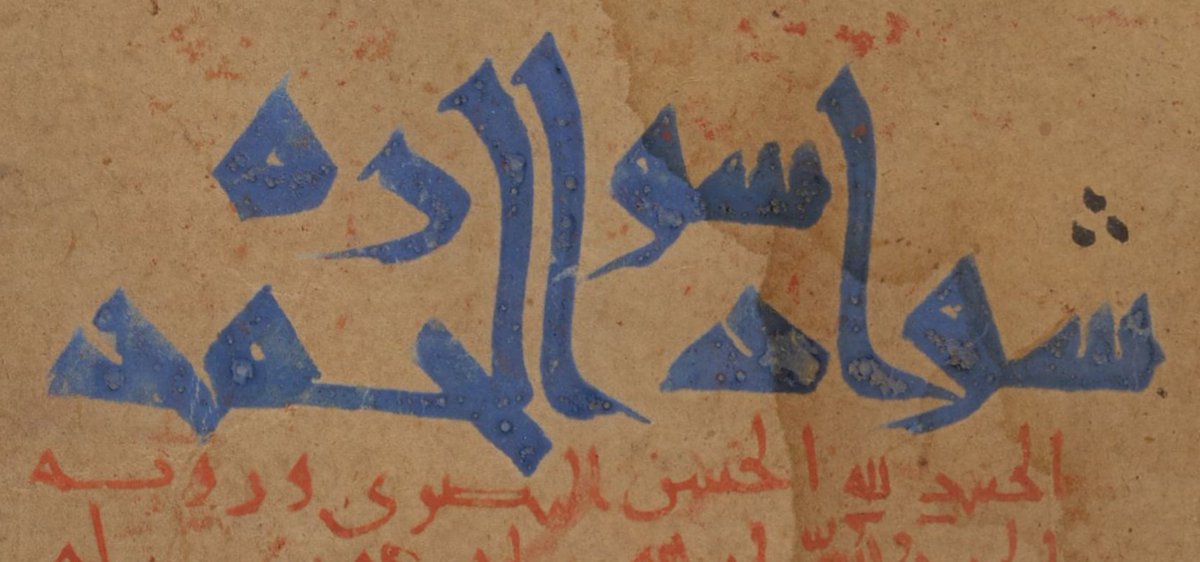

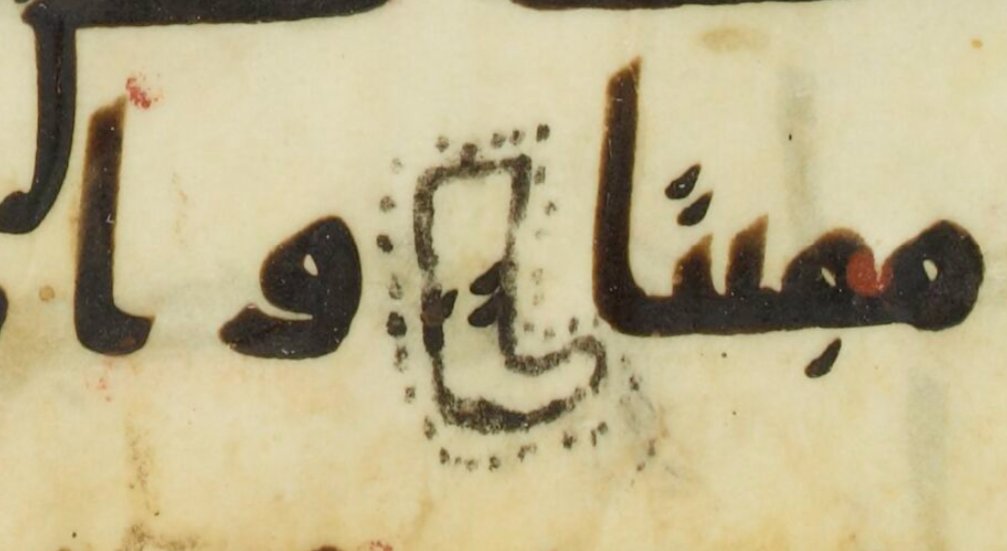

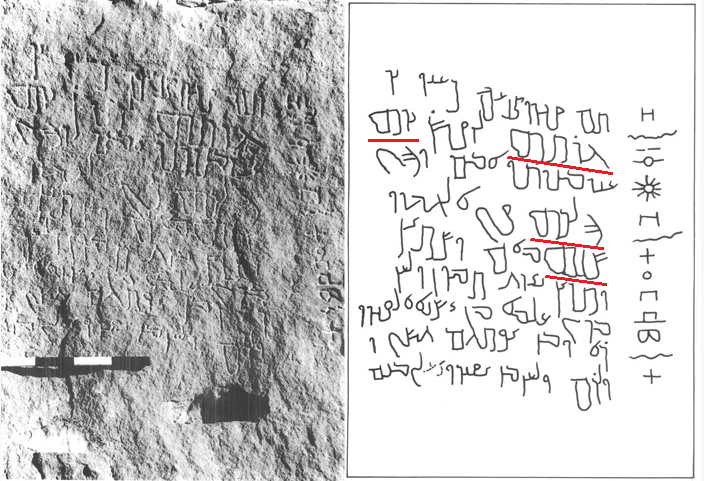

As the Nabataean script progresses into what Laïla Nehmé has dubbed "transitional Nabataeo-Arabic", the final tāʾ develops a distinctive loop, seen for example in the name ḥāriṯat in JSNab 17 where it stands next to the non-final tāʾ (see also <brt>, <hlkt> and <šnt>).

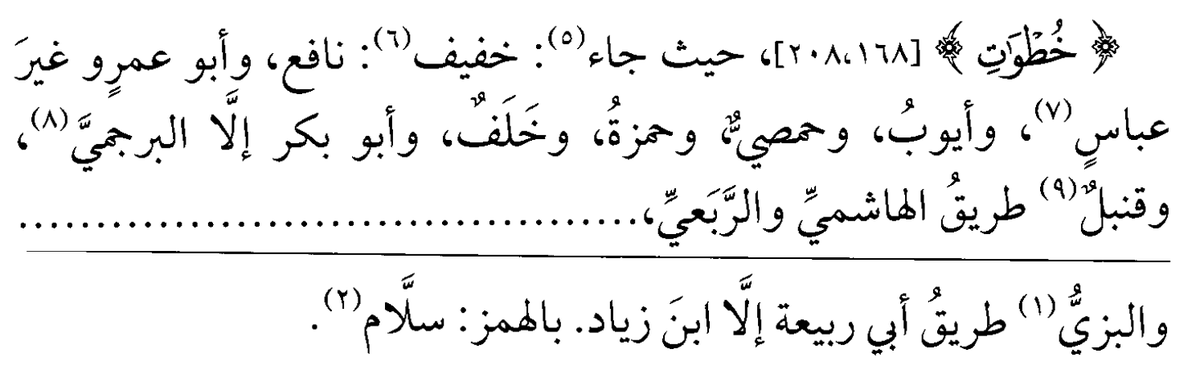

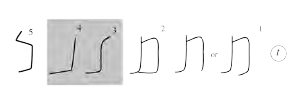

Eventually the non-final shape develops into a kind of zig-zag shape, where the tāʾ merges with the yāʾ, to then eventually become a simple denticle where it merges with bāʾ and nūn. This is a clear gradual process, and we can basically trace it across the epigraphic record.

There is no good evidence yet for a gradual development of the loopy final tāʾ into the final bāʾ shape as we know it today, and no good explanation for its suddent shift. It's surprising because word-final signs that merge elsewhere tend to remain distinct (ن ب ي; ف ق; ح جـ).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter