⚠️WOKE CONTENT⚠️

Dallas, TX - On March 10, 1910, Allen Brooks was lynched while awaiting court proceedings. He was accused of raping Mary Beuvens, a young White toddler in late February 1910. He proclaimed his innocence as there was no proof (cont)

blackpast.org/african-americ…

Dallas, TX - On March 10, 1910, Allen Brooks was lynched while awaiting court proceedings. He was accused of raping Mary Beuvens, a young White toddler in late February 1910. He proclaimed his innocence as there was no proof (cont)

blackpast.org/african-americ…

he committed a crime. Brooks was taken to jail and formally indicted a day later. He was moved to several jails outside the city limits due to concerns for his safety. He was returned to the Dallas courthouse where a mob of hundreds gathered. (cont)

timeline.com/allen-brooks-d…

timeline.com/allen-brooks-d…

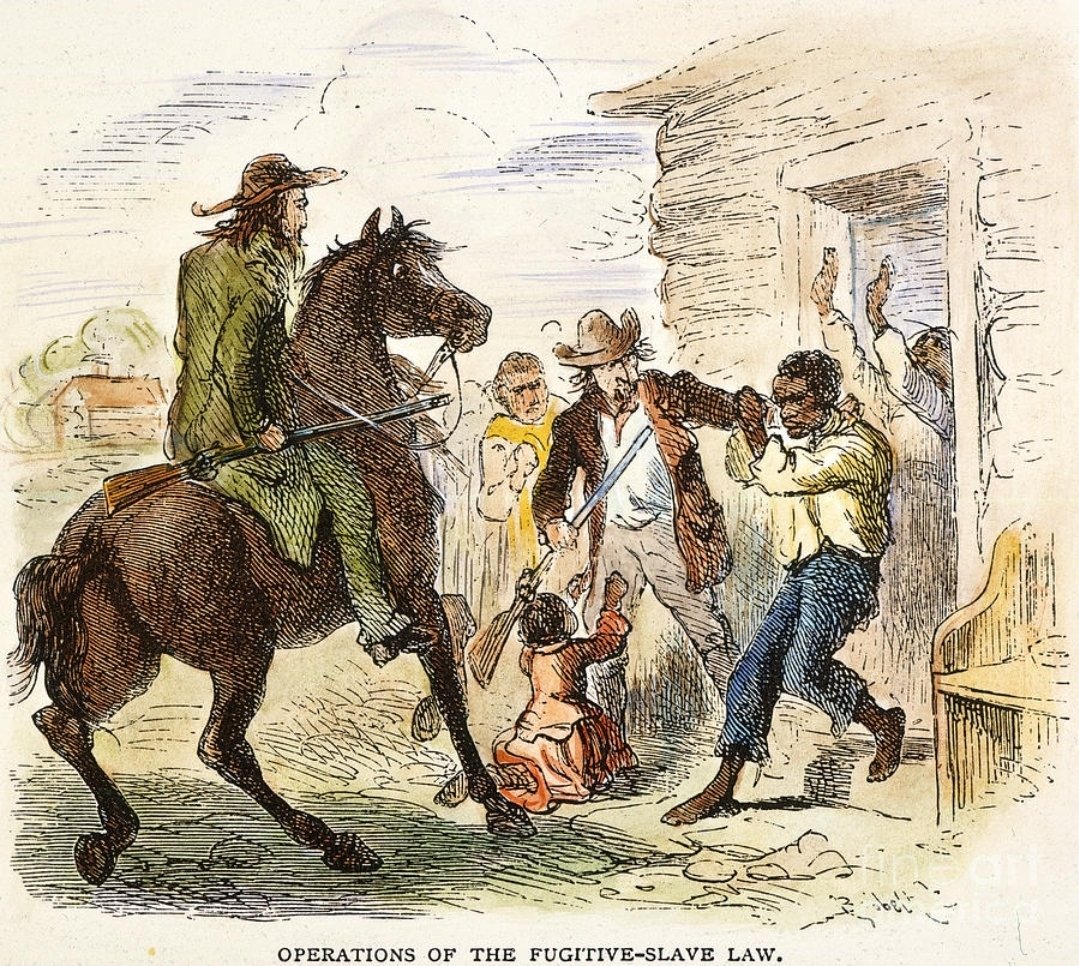

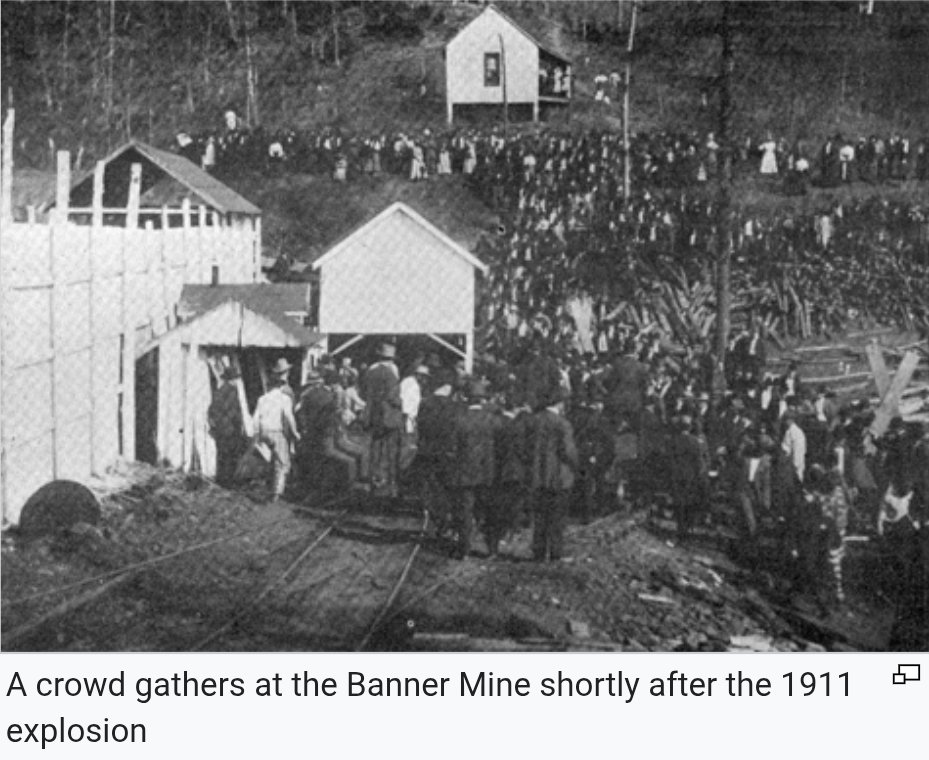

After easily penetrating a human pillar of more than 100 law enforcers, the mob pushed its way through, demolishing doors to overrun the courthouse. A frenzied search for Brooks led to a jury room, where he was discovered hunkered down in a corner. A rope was tied around (cont)

his neck and he was pulled from the outside through a second story window. One report described Brooks as fighting “like a tiger” before being pulled through a window onto the street below. He landed headfirst and was beaten and stomped(cont)

until his face was a bloodied pulp. There was no justice meted by a judge or jury that day; only mob vengeance. He was dragged by automobile to the corner of Main and Akard where was hanged from a telephone poll near the giant arch; his body became a spectacle for (cont)

entertainment. By the time Dallas's undertaker arrived at the scene, he found that Brooks' body had been reduced to a "shapeless mass of flesh," with his undershirt and flannel—the only clothes still on his body—in tatters. The mob had torn pieces of his clothing off for (cont)

souvenirs. Out of this lynching, the ultimate souvenir is the postcards that were mass produced.

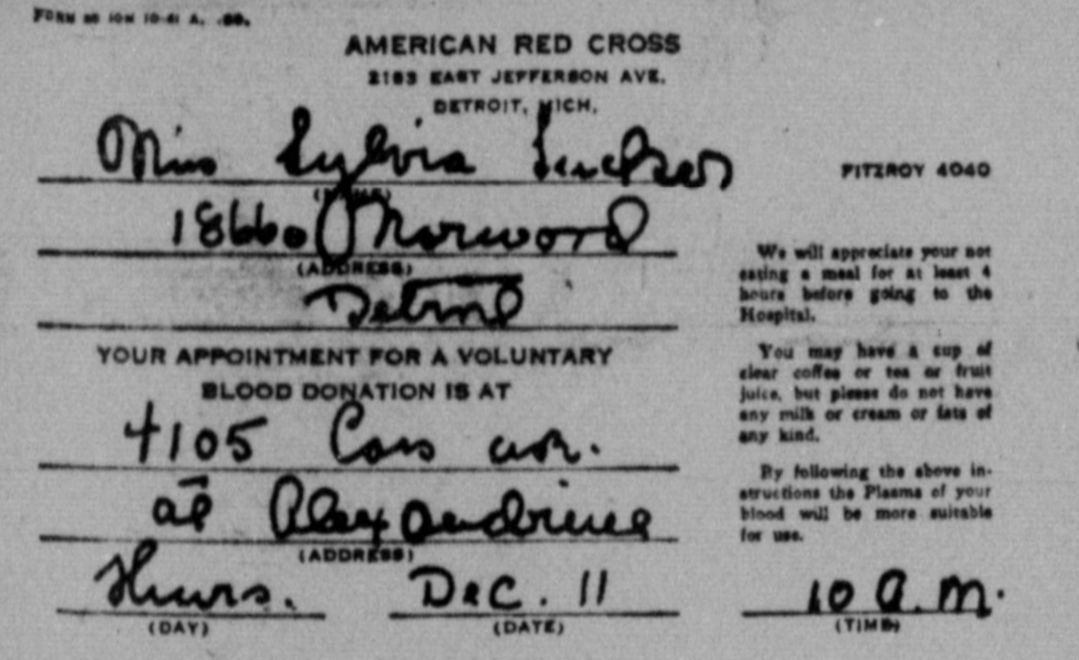

One such postcard included written commentary on the back: "This is a token of a great day we had in Dallas, March 3, a negro was hung for an assault on a three year old girl."(cont)

One such postcard included written commentary on the back: "This is a token of a great day we had in Dallas, March 3, a negro was hung for an assault on a three year old girl."(cont)

No one was held accountable for Brooks' death; not even the law enforcement officers who did not use their weapons to protect him.

The site of his lynching remained unmarked for more than century until 2021.

#ResistanceRoots

#DedicatedToTam ✡️❤️⚘️🕊

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_…

The site of his lynching remained unmarked for more than century until 2021.

#ResistanceRoots

#DedicatedToTam ✡️❤️⚘️🕊

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh