Changes to the Bar exam so far don't seem to have made a dent in the race differences in performance on it.

How large are these differences? In the latest year, 2022, the Black-White gap in California Bar pass rates was 0.97 SDs.

And this matters because we expect a threshold

How large are these differences? In the latest year, 2022, the Black-White gap in California Bar pass rates was 0.97 SDs.

And this matters because we expect a threshold

https://twitter.com/RichardHanania/status/1660276679066132480

to practice (the Bar exam) to reduce subsequent performance gaps.

But how much should those gaps be reduced?

Let's simulate to find out!

@_twolfram recently provided an estimate for British lawyers' IQs of 110.31: sciencedirect.com/science/articl….

Let's go ahead and assume

But how much should those gaps be reduced?

Let's simulate to find out!

@_twolfram recently provided an estimate for British lawyers' IQs of 110.31: sciencedirect.com/science/articl….

Let's go ahead and assume

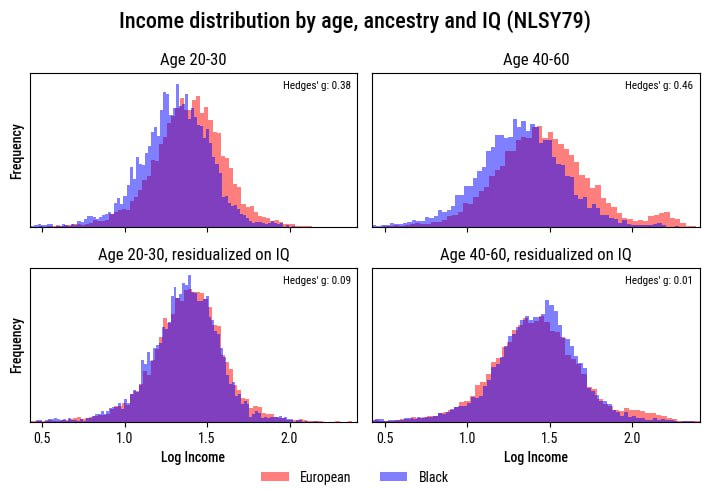

there's a threshold that's 0.67 SDs (10 points) above the higher-performing of two groups with equal variances who are separated by 0.97 d.

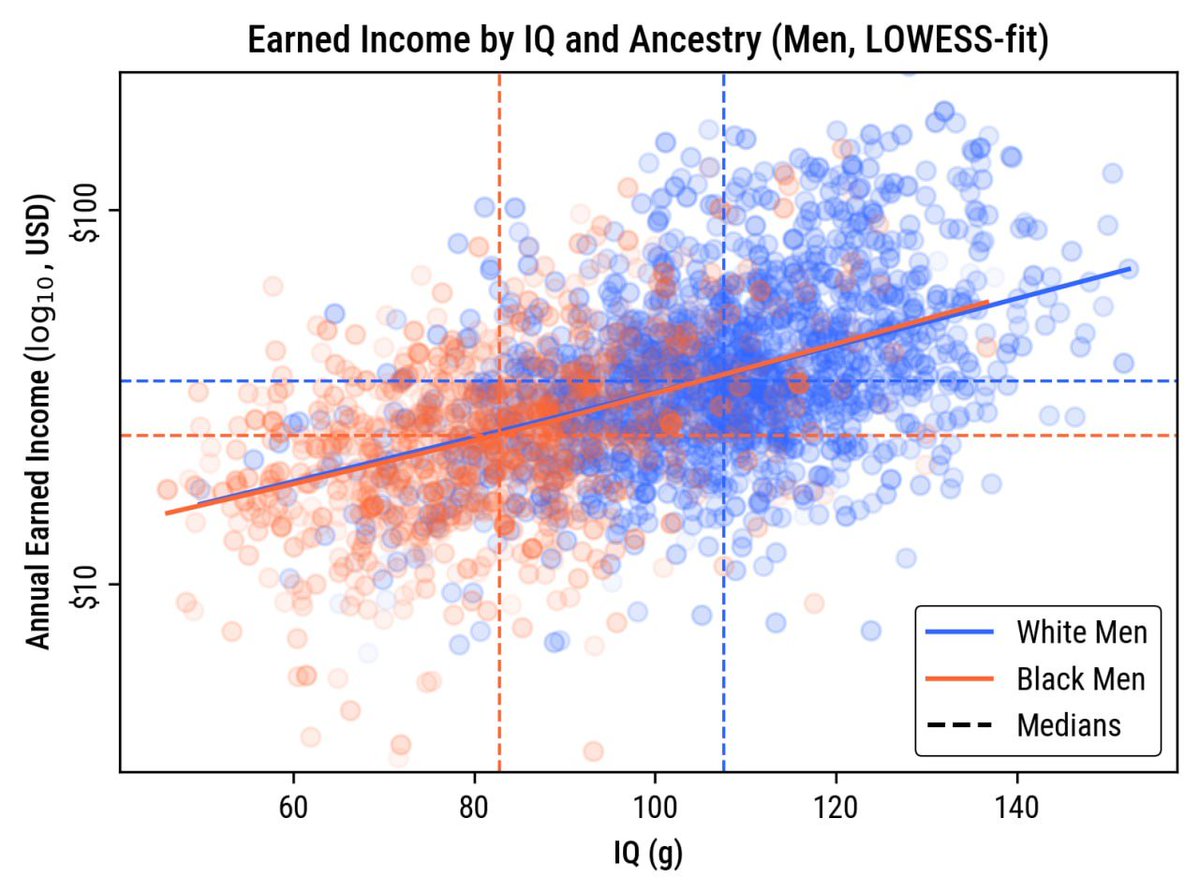

With simulated group sizes of one million persons each, the mean differences decline, and the SDs do too. The new gap is 0.412 d.

With simulated group sizes of one million persons each, the mean differences decline, and the SDs do too. The new gap is 0.412 d.

But we know that the 0.97 d gap is an underestimate due to range restriction.

Using MBE scores, it looks like the unrestricted gap should be more like 1.22 d. That leaves us with a 0.537 d gap above the threshold.

Do we have subsequent performance measures?

Yes! We have three:

Using MBE scores, it looks like the unrestricted gap should be more like 1.22 d. That leaves us with a 0.537 d gap above the threshold.

Do we have subsequent performance measures?

Yes! We have three:

- Complaints made against attorneys

- Probations

- Disbarments

For men, the gaps, in order, are 0.576, 0.513, and 0.564 d. For women, the gaps are 0.576, 0.286, and 0.286 d.

Men fit expectations and women apparently needed less discipline.

- Probations

- Disbarments

For men, the gaps, in order, are 0.576, 0.513, and 0.564 d. For women, the gaps are 0.576, 0.286, and 0.286 d.

Men fit expectations and women apparently needed less discipline.

These gaps probably replicate nationally.

For example, here are Texas pass rates from 2004 - a 0.961 d Black-White first-pass gap. The 2006 update to these figures raised the gap to 0.969 d.

For example, here are Texas pass rates from 2004 - a 0.961 d Black-White first-pass gap. The 2006 update to these figures raised the gap to 0.969 d.

Since all of the people included in these statistics went to ABA-accredited schools, they all had the opportunity to learn what was required to perform well on these tests.

But just like the Step examinations for medical doctors, the gaps on the tests and in real life remain.

But just like the Step examinations for medical doctors, the gaps on the tests and in real life remain.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh