Meekness is a martial virtue—

I am on a mission to reclaim the good name of the virtues, and rn I want to talk about one that has been slandered to death: meekness. 🧵

I am on a mission to reclaim the good name of the virtues, and rn I want to talk about one that has been slandered to death: meekness. 🧵

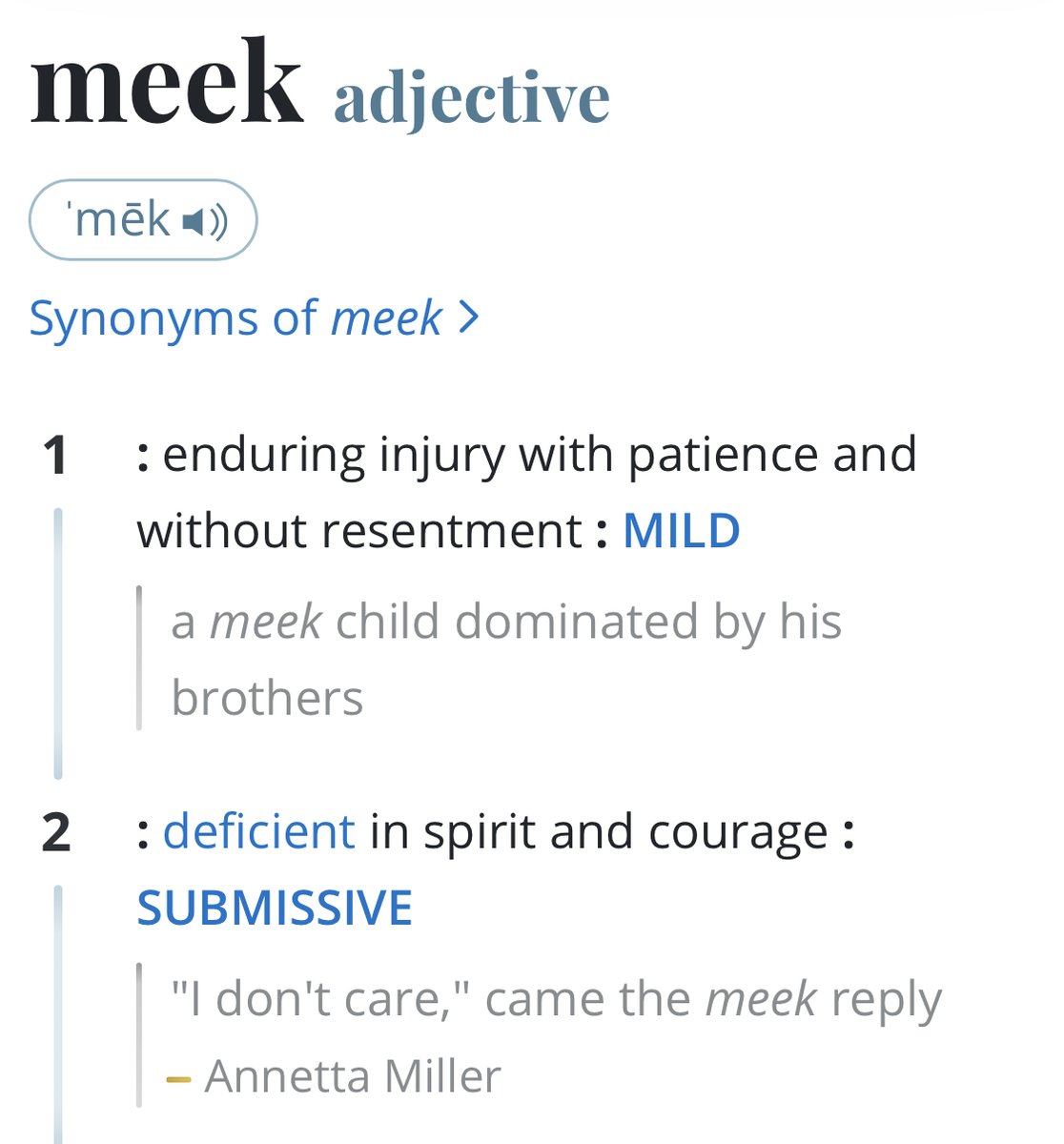

If you look in contemporary dictionaries, you’ll probably see a mild primary definition, followed by a lame secondary one. Perfect example from Merriam-Webster:

Cambridge likewise offers a telling example of usage:

“He’s slight, meek, and balding, and hardly heroic.”

“He’s slight, meek, and balding, and hardly heroic.”

In other words, the meek fellow has no choice but to be meek, because it’s not like he could do anything about injuries and insults anyways. As Churchill once said of a rival, “He’s a modest man who has a good deal to be modest about.”

Few spirited men could understand meekness on these terms and still think it worth striving for. This is a particularly live issue for English-speaking Christians, given the use of meek in translations of the New Testament. Does the Lord ask us to be pushovers? twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Thomas Aquinas offers a definitive and refreshing No! Meekness (mansuetude), he writes, “restrains the onslaught of anger” and “properly mitigates the passion of anger.” twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

So when the Lord proclaims, “Blessed are the meek,” he isn’t telling us to be easily imposed upon, deficient in courage. He instead challenges us to have authority over our anger, the ability to direct its power rather than being directed by it.

As I mentioned above, the traditional understanding of meekness actually lends itself to martial purpose.

George Patton once noted that wars are not won by winning battles; they are won by choosing battles. Meekness is crucial in helping us choose the right battles.

George Patton once noted that wars are not won by winning battles; they are won by choosing battles. Meekness is crucial in helping us choose the right battles.

Without meekness we fly into a rage and our battles are chosen for us by those instigators who know how to play us. With proper meekness, though, we gain the power to choose which provocations we answer; we are ruled by good sense rather than by automatic reflexes.

You could actually say that the man without meekness is weak. He is weak because he cannot control his anger and he exhausts his energy over trifles.

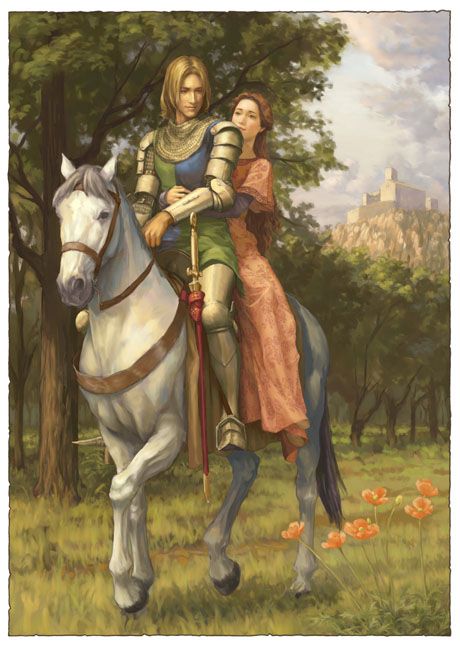

There are fine examples in the Arthurian literature. One of my favorite involves Tennyson's telling of Sir Geraint's story. When the knight is openly and needlessly disrespected by a small man, his hand goes for his sword. Then he thinks better of it.

Tennyson writes:

"But he, from his exceeding manfulness

And pure nobility of temperament,

Wroth to be wroth at such a worm, refrained

From even a word."

"But he, from his exceeding manfulness

And pure nobility of temperament,

Wroth to be wroth at such a worm, refrained

From even a word."

The virtue of meekness allows Geraint to pause long enough to realize that this person and this quarrel are unworthy of his time and energy.

It’s worth adding that Geraint is rewarded for his restraint. His decision sets in motion the events which will lead to his encounter with a beautiful young lady of a noble but fallen family who needs a champion to fight for her.

Enid will become the best wife a man could ever hope to have, and Geraint would never have met her if he had given the small man a buffet like he deserved.

True meekness, contrary to what we’ve been told, is not the sissy’s virtue, not the virtue for soft, effete men.

This is a real virtue for real men. It is especially important for fighters.

This is a real virtue for real men. It is especially important for fighters.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter