Inflation: it's "complicated"

What's been causing inflation is important. Get it wrong, and we get the wrong policies. And we learn the wrong lessons for the future.

What's been causing inflation is important. Get it wrong, and we get the wrong policies. And we learn the wrong lessons for the future.

Today’s post is my reaction to “What Caused the U.S. Pandemic-Era Inflation?“ by Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard @ojblanchard1. Any errors here are my own.

Go to the authors, too: here’s the paper, news coverage, a video, and a tweet thread.

Go to the authors, too: here’s the paper, news coverage, a video, and a tweet thread.

https://twitter.com/ojblanchard1/status/1661746889296060424

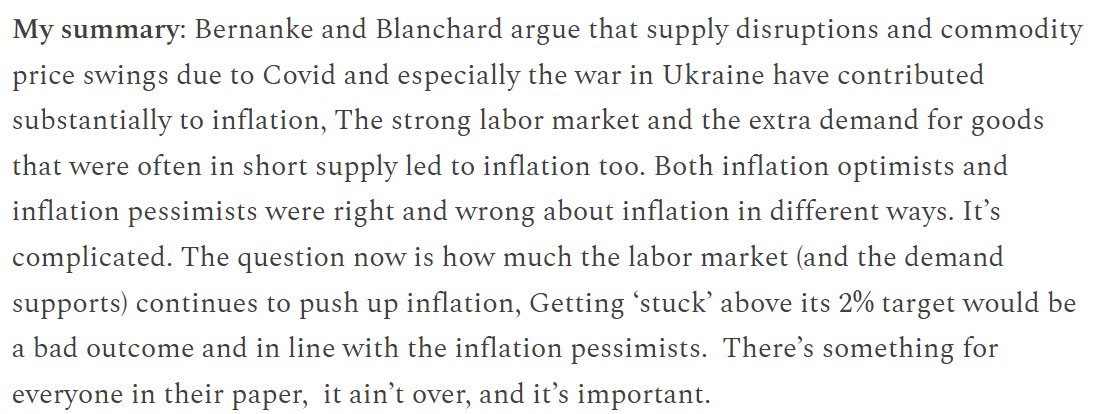

My high-level summary:

Both inflation optimists and inflation pessimists were right and wrong about inflation in different ways. There's something for everyone in the debate here.

Both inflation optimists and inflation pessimists were right and wrong about inflation in different ways. There's something for everyone in the debate here.

Here's their Money Chart:

Shortages (yellow), food (light blue), and energy (dark blue) explain spikes in inflation more than labor market (red). Even so, as the supply-side contributions wane, those from the labor market have persisted and could keep inflation staying elevated.

Shortages (yellow), food (light blue), and energy (dark blue) explain spikes in inflation more than labor market (red). Even so, as the supply-side contributions wane, those from the labor market have persisted and could keep inflation staying elevated.

Bernanke and Blanchard’s model-based findings largely align with the statistical decomposition by Adam Shapiro, an economist at the San Francisco Fed. Of course, there is research that comes to the opposite conclusion.

In my opinion, it’s impossible to look at inflation in recent years and say it’s only demand and then blame the Rescue Plan and the slow-to-lift-off Fed. Likewise, it’s impossible to say it was only supply. This debate matters because it informs monetary and fiscal policy.

Workers have the upper hand, or do they?

How strong the labor market is key. And what’s driving wages.

Nominal wage growth in their model depends on three elements:

-Inflation expectations

- aspirational real wage to catch up to past inflation.

- Labor market tightness.

How strong the labor market is key. And what’s driving wages.

Nominal wage growth in their model depends on three elements:

-Inflation expectations

- aspirational real wage to catch up to past inflation.

- Labor market tightness.

Ok, so how do they assess the labor market: the vacancy rate, that is. the ratio of job openings to unemployed persons. By that measure the labor market is hot.

The Fed uses job openings too. But there are problems with that thermometer of the labor market. See the report from @PrestonMui at @employamerica employamerica.org/researchreport… Plus, the vacancy rate is the tightest of measures.

Here's a snippet from the report.

Rather than lean heavily on the vacancy rate (as Bernanke and Blanchard did), it is better to track several measures. Vacancies point to more tightness than nearly every other measure.

Rather than lean heavily on the vacancy rate (as Bernanke and Blanchard did), it is better to track several measures. Vacancies point to more tightness than nearly every other measure.

The "catch-up" or "aspiration wages" is a neat addition to their wage equation. It's not standard in macro models. It's a clever way to see if wage-price spirals could take hold because workers have bargaining power. They find no evidence of it affecting wages.

Inflation expectations lookin’ good.

Inflation expectations are anchored, albeit near the top end of the range, and did not move much in the past three years. And that’s very good. Had expectations de-anchored (moved up persistently, we would have more than a 5% fed funds rate.

Inflation expectations are anchored, albeit near the top end of the range, and did not move much in the past three years. And that’s very good. Had expectations de-anchored (moved up persistently, we would have more than a 5% fed funds rate.

Other measures of inflation, like the Michigan Survey, tell a similar story: anchored expectations. Inflation remains elevated, and there is no reason to declare victory. Inflation expectation is reassuring that markets and consumers believe we will get inflation back to normal.

What’s missing?

Bernanke and Blanchard’s model allows for worker bargaining power in a “catch-up” concept. But there's nothing on market power. Watch out for wage-price spirals, as in the 70s that pushed inflation up. What about price-price spirals? What about profits?

Bernanke and Blanchard’s model allows for worker bargaining power in a “catch-up” concept. But there's nothing on market power. Watch out for wage-price spirals, as in the 70s that pushed inflation up. What about price-price spirals? What about profits?

Isabella Weber @IsabellaMWeber has been at the forefront of how crises like the pandemic and the war in Ukraine allow firms to raise prices aggressively, even more than their rising costs.

Bernanke and Blanchard briefly discuss the “markups” of price over cost. That explains some, but not all, of the rise in markups, leaving reasons to keep studying markups since the pandemic began.

Excellent piece by @EmilyRPeck axios.com/2023/05/18/onc…

In closing

Inflation is complicated.

According to Bernanke and Blanchard, no single factor has pushed up inflation. Instead, it’s been a series of evolving factors. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine, policy responses, a strong labor market, and changes in behavior all matter.

Inflation is complicated.

According to Bernanke and Blanchard, no single factor has pushed up inflation. Instead, it’s been a series of evolving factors. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine, policy responses, a strong labor market, and changes in behavior all matter.

Bernanke and Blanchard’s summary of their paper is a good place to close it out. #goteam

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter