#OTD #Onthisday 28 May, 1754, Major Washington of the Virginia Regiment fought his first battle at Jumonville Glen, which ended in the murder of Ensign Jumonville. In Voltaire's words, it was a "torch lighted in the forests of America" that "set all Europe in conflagration.”

1/🧵

1/🧵

At 10 p.m. on the 27th, Washington set out from his camp in the Great Meadows, Pennsylvania with a party of about 40 Virginia militiamen. They had no idea where they were headed for, and what catastrophic liability their would come to bear.

(Wa. to Dinwiddie, 29 May 1755)

(2/46)

(Wa. to Dinwiddie, 29 May 1755)

(2/46)

The only intelligence available to them was the unexpected Express from the Half-King, received by Washington two hours ago-that "he was coming to join us, they had seen along the road the tracks of two [Frenchmen] which went down into a gloomy hollow, and that he imagined

(3/46)

(3/46)

that the whole party was hidden there."

But tormented by "a heavy rain, with the night as black as pitch and by a path scarcely wide enough for a man," the young Major could not even configure the road ahead, let alone reunite with his only native intermediary.

(4/46)

But tormented by "a heavy rain, with the night as black as pitch and by a path scarcely wide enough for a man," the young Major could not even configure the road ahead, let alone reunite with his only native intermediary.

(4/46)

"We were often astray for 15 or 20 minutesbefore we could find the path again, and often we would jostleeach other without being able to see. We continued our march all night long..." wrote Washington in his journal.

(5/46)

(5/46)

Seven men were lost en route, but had to be left behind.

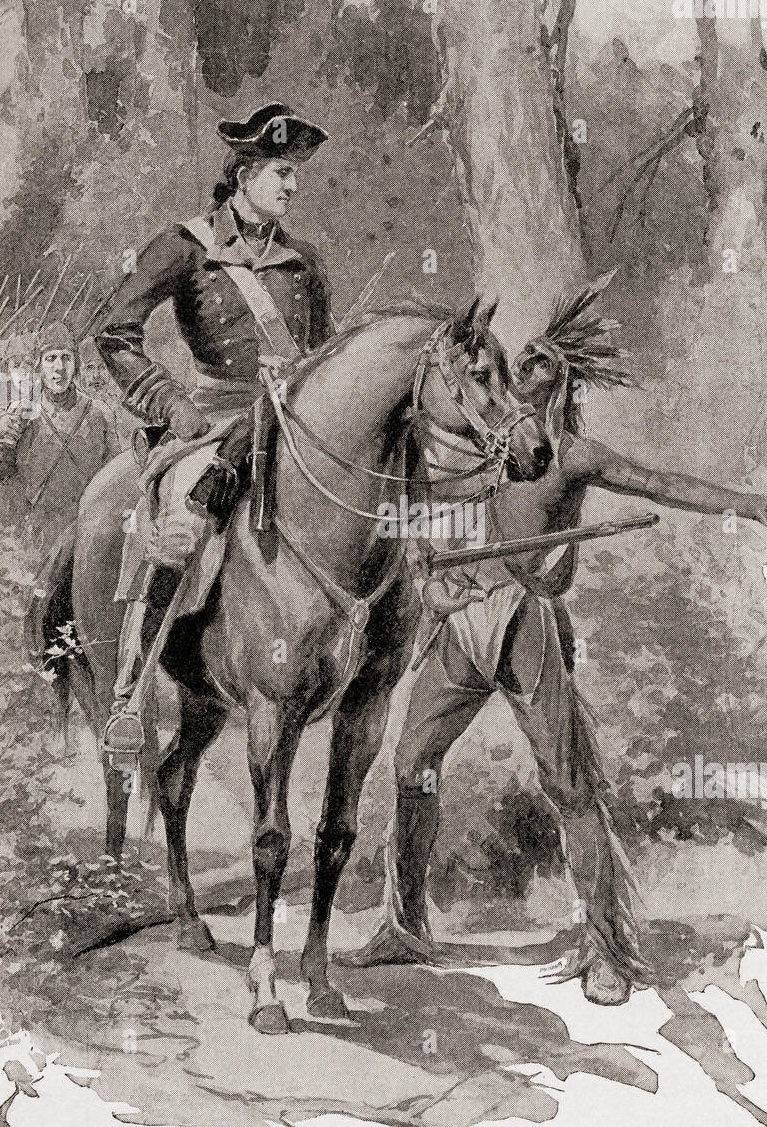

Only by the sunrise did the torrent subside, and the lanky Virginian finally found himself at the bivouac of the Half-King and his braves. They held a brief council of war, where it was "decided to strike jointly."

(6/46)

Only by the sunrise did the torrent subside, and the lanky Virginian finally found himself at the bivouac of the Half-King and his braves. They held a brief council of war, where it was "decided to strike jointly."

(6/46)

The Half-King, with Monacatoocha and a few other Delaware scouts, guided Washington's men into a narrow tract. Half a mile later, they discovered the French camp at the spot Washington described to Dinwiddie as "a very obscure place surrounded with Rocks."

(To Dinwiddie)

(7/46)

(To Dinwiddie)

(7/46)

Here, the 22-year-old Virginian officer about to have his first taste of battle and the 58-year-old chief, containing his skepticism about his naive companion, discussed "arrangements to surround them, and...began to march in Indian fashion, one after the other."

(Journal)

(8/46)

(Journal)

(8/46)

Although no written plan of action had been documented, primary accounts of the skirmish and the secondary analysis by Paul R. Misencik (2014) enable one to infer the following.

Washington split his small force into two groups. The first column consisted of himself,

(9/46)

Washington split his small force into two groups. The first column consisted of himself,

(9/46)

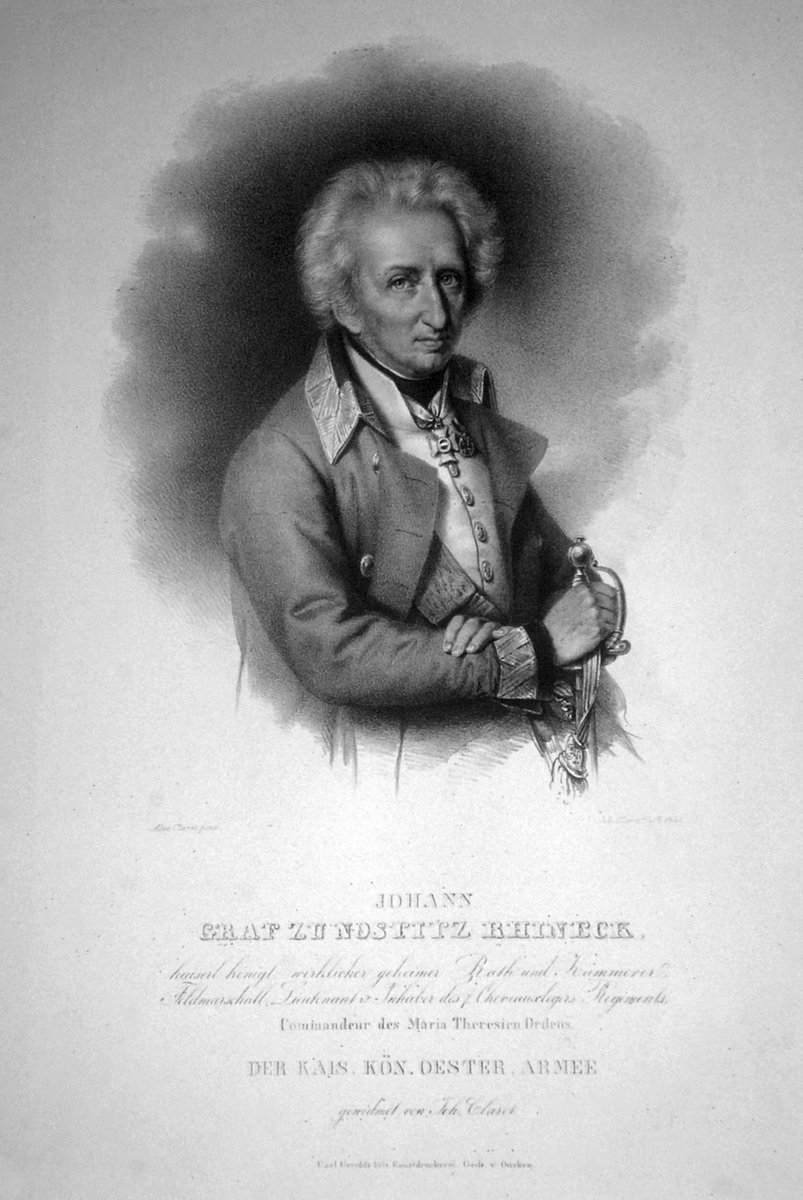

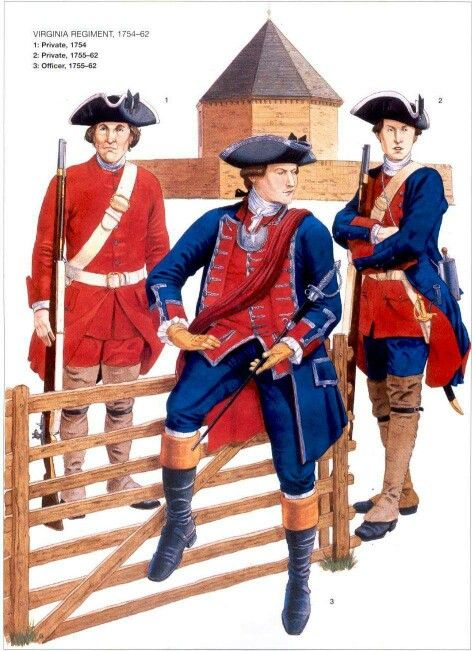

Captan Peter Hogg (1703-1782), twenty men from the Virginia Regiment, "and the Half King [Tanaghrisson] with his Indians consisting of thirteen."

(John Shaw, Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia: 19 Sept. 175)

(10/46)

(John Shaw, Pennsylvania Gazette. Philadelphia: 19 Sept. 175)

(10/46)

The second was a party of 20 men under Captain Adam Stephen (1718-1791) and William La Péronie,a France-born ensign in the militia. The two did not know that the prey who had constantly eluded them was fast asleep, just a mile away.

(11/46)

(11/46)

Lieutenant La Force, whom they had been commissioned by Washington to pursue on 11 May, had slipped away to the Youghiogany and conducted an abortive raid on Gist's plantation two days ago.

(Journal)

(12/46)

(Journal)

(12/46)

Having observed that the direct, northerly path to the enemy post was not adequately concealed by the rocks, Washington decided to spread out his own column, the right flank thereafter. The 20 militiamen would continue marching northward,

(13/46)

(13/46)

while the 13 Indians, taking advantage of the woods, would make a detour towards the northern side of the glen opposite to Washington's position. On the left flank, shielded by imposing cliffs, Stephens was made to occupy one of their peak.

(14/46)

(14/46)

"I thereupon in conjuction with the Half King & Monacatoocha, formd a disposion to attack them on all sides," Washington would write to Dinwiddie on the next day.

(Wa. to Dinwiddie; Misencik, George Washington and the Half-King Chief Tanacharison (2014))

(15/46)

(Wa. to Dinwiddie; Misencik, George Washington and the Half-King Chief Tanacharison (2014))

(15/46)

Who spotted the other first, who fired first, and the exact sequence of what happened still remains blurry. The prevailing consensus among the eyewitnesses is that the engagement broke out between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m., in broad daylight, and lasted no longer than 15 min.

(16/46)

(16/46)

The Virginians claimed that the French had been the first to be alerted and show aggression, and the French vice versa.

Stephen, in his testimony publicized by the Pennsynvania Gazette in the following September, stated that:

(17/46)

Stephen, in his testimony publicized by the Pennsynvania Gazette in the following September, stated that:

(17/46)

"At Day-light we put our Arms in the best Order we could (for it rained without Intermission) and came up with the French to Breakfast. A smart Action ensu'd; their Arms and Ammunition were dry, being shelter'd by the Bark Huts they slept in;

(18/46)

(18/46)

we could not depend on ours, and therefore keeping up our Fire, advanced as near as we could with fixt Bayonets, and received their Fire."

(Stephen, Pennsylvania Gazette, September 19, 1754; Marcel Treudel, The Jumonville Affair (1952))

(19/46)

(Stephen, Pennsylvania Gazette, September 19, 1754; Marcel Treudel, The Jumonville Affair (1952))

(19/46)

While Stephen implied that the French were the first to load their muskets, Washington's journal entry actually obfuscated the responsibility of the enemy:

"We had advanced quite near them according to plan, when they discovered us. Then I gave my men orders to fire."

(20/46)

"We had advanced quite near them according to plan, when they discovered us. Then I gave my men orders to fire."

(20/46)

Private John Shaw of the Virginia Regiment, who did not partake in the mission, summarized what he had heard from his colleagues:

"...[S]ome of [the French] were asleep and some eating, but haveing heard a Noise they were immediately in great Confusion and

(21/46)

"...[S]ome of [the French] were asleep and some eating, but haveing heard a Noise they were immediately in great Confusion and

(21/46)

betook themselves to their Arms and as this Deponent has heard, one of [the French] fired a Gun upon which Col. Washington gave the Word for all his Men to fire."

None of them, however, mattered when Washington was unaware of the identity of his enemy.

(22/46)

None of them, however, mattered when Washington was unaware of the identity of his enemy.

(22/46)

The 35 Frenchmen sheltered at the glen, commanded by Joseph Coulon de Villiers, sieur de Jumonville (1718–1754), were not out to get the Half-King. In fact, they were on a mission to hand the English an official ultimatum against trespassing on the Belle Rivière

(23/46)

(23/46)

-known as the Ohio River to the English-issued by its commandant Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur (1705-1775).

Washington's attack on the envoys, whether it was in response to the French volleys, would irreversibly tarnish his reputation to both sides.

(24/46)

Washington's attack on the envoys, whether it was in response to the French volleys, would irreversibly tarnish his reputation to both sides.

(24/46)

In fifteen minutes, the Virginians discharged their muskets twice, and the French struggled to reciprocate with their "entire fire." Jumonville, injured in combat, called for a retreat in the northerly direction.

(Contrecoeur to Duquesne, 2 June 1754, Moreau)

(25/46)

(Contrecoeur to Duquesne, 2 June 1754, Moreau)

(25/46)

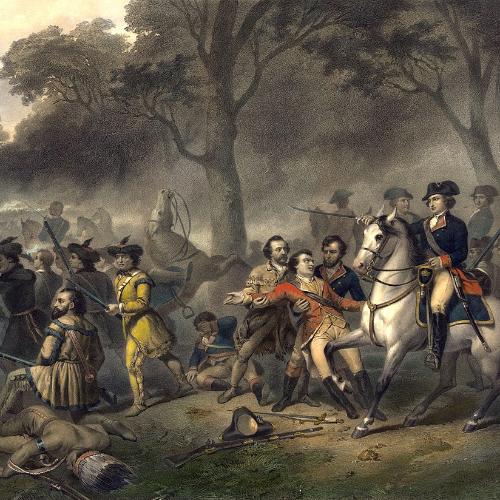

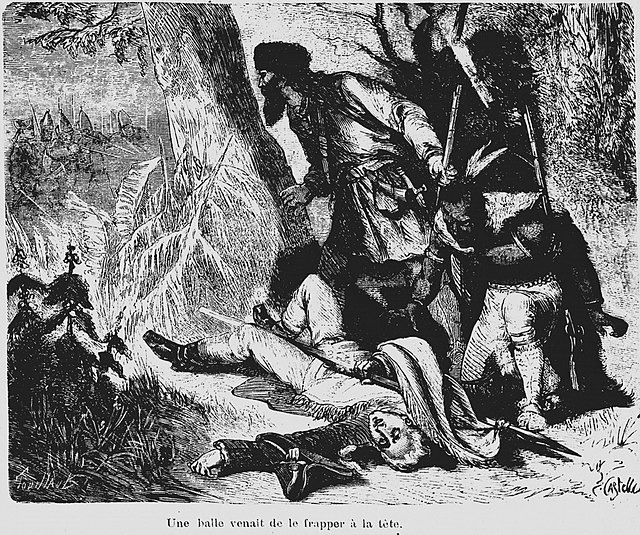

But just as Washington had designed, the French soon found themselves hounded in every corner; Stephen's men, emerging from the west, bayonetted the fleeing, and the Half-King's scouts, from the north, brandished their tomahawks.

(Washington, Journal; Stephen; Shaw)

(26/46)

(Washington, Journal; Stephen; Shaw)

(26/46)

On what exactly happened next, the Virginian eyewitnesses remained rather discreet-perhaps in a concerted effort to evade the blame. Washington, in his diary, limited the description of the aftermath to mostly numerical information:

(27/46)

(27/46)

"We killed M. de Jumonville, commanding this party, with nine others; we wounded one and made 21 prisoners, among whom were M. La Force, M. Drouillon, and two cadets. The Indians scalped the dead, and took most of their arms."

(28/46)

(28/46)

Stephen, too, merely repeated that "Joumonville, and eleven private Men were killed on the Spot."

However, testimonies from the French and Canadian survivors contained incomparably lurid and revolting details.

(29/46)

However, testimonies from the French and Canadian survivors contained incomparably lurid and revolting details.

(29/46)

On 2 June, a Canadian named Monceau was seen limping his way into Contrecoeur's headquarter at Fort Duquesne. Mentioned by Francis Parkman as the only survivor "who had fled at the beginning of the fray," he told Contrecoeur that

(30/46)

(30/46)

they had found themselves encircled "by the English on one side and the Savages on the other side" at 7 a.m. on the 28th. After standing "two discharges from the Englishman," Jumonville brought an interpretor to read the attackers a summon from Contrecoeur:

(31/46)

(31/46)

"...I am sending M. de Jumonville to see for himself and, in case he finds you there, to summon you in the name of the King, by virtue of the orders which I have from my General, to withdraw peacefully with your troop."

(32/46)

(32/46)

Otherwise, Sir, you will force me to compel you to do it by whatever means I think most effective for the honor of the King's arms."

According to Monceau, the English, not the Indians, renewed the assault even before the official finished reading the document,

(33/46)

According to Monceau, the English, not the Indians, renewed the assault even before the official finished reading the document,

(33/46)

"so that [the French] found themselves in a platoon in the midst of the English and Indians." This infuriated Contrecoeur, who had been desperately waiting for Jumonville's reply for four days.

"I believe, sir," he wrote in disbelief to Marquis Duquesne (1770-1778),

(34/46)

"I believe, sir," he wrote in disbelief to Marquis Duquesne (1770-1778),

(34/46)

the Governor-General of New France, "that you will be surprised at the unworthy manner in which the English behave; it is what has never been seen, even among all the least civilized Nations."

(To Duquesne, 2 Jun; To Jumonville, 23 May 1754, The Contrecoeur Papers)

(35/46)

(To Duquesne, 2 Jun; To Jumonville, 23 May 1754, The Contrecoeur Papers)

(35/46)

But more shocking testimony arrived on the morning of 30 June. Denis Kaninguen, a Catholic Iroquois deserter from either the English or the French camp, claimed that:

"[Jumonville] had advanced to communicate his orders

(36/46)

"[Jumonville] had advanced to communicate his orders

(36/46)

to the English commander, in spite of the musket-fire the commander had aimed at him! On hearing the reading of it, he withdrew to his men whom he ordered to fire on the French. M. de Jumonville was wounded, and had fallen.

(37/46)

(37/46)

[Tanaghrisson], an Indian, came to him and said,

'You are not dead yet, my father [Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!],

and struck him several blows with his hatchet, which killed him."

Kaninguen himself narrowly escaped his pursuer on horseback,

(38/46)

'You are not dead yet, my father [Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!],

and struck him several blows with his hatchet, which killed him."

Kaninguen himself narrowly escaped his pursuer on horseback,

(38/46)

"whose thigh he broke with a rifle shot" and whose horse he seized to gallop "at full speed to the French camp."

The tragic death of Jumonville, summarized by Lieutenant Joseph-Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry (1682-1756), commandant at Fort Presque Isle on 7 July,

(39/46)

The tragic death of Jumonville, summarized by Lieutenant Joseph-Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry (1682-1756), commandant at Fort Presque Isle on 7 July,

(39/46)

served to complete the narrative of martyrdom, which would circulate in Paris via the chronicle of court historian Jacob-Nicholas Moreau (1717-1803), L'observateur Hollandois, a periodical written by Moreau from 1755 to 1759, and Le Moniteur.

(40/46)

(40/46)

France, in turn, would enter the war with an immense propaganda advantage. L'affaire Jumonville, as C.A. Crouch argued in Nobility Lost (2014), "became a rallying point for the new ideals of la patrie and la nation because he was murdered under a white flag of truce."

(41/46)

(41/46)

For Washington, he walked out of his first battlefield with nothing but an irreversibly tarnished reputation. Nor did he succeed in winning his ally's trust; when he informed the Half-King of Dinwiddie's wish to meet him at Winchester, the Indian replied that

(42/46)

(42/46)

"that was impossible for the time being, as his men were in too grave danger from the French whom they had just attacked; that he must send messengers to all the allied nations to invite them to take up the hatchet."

(43/46)

(43/46)

The cunning chief, to worsen the volatile situation, sent the message himself "with a French scalp, to the Delawares." But Washington agreed with the Half-King's opinion on the summon, that the French "they had evil designs, and that it was a mere pretext."

(Journal)

(44/46)

(Journal)

(44/46)

As late as 1759, the haunting tale of L'Affaire de Jumonville would resonate through the public minds in Paris and Quebec. Written by Antoine-Léonard Thomas, the poem "Jumonville" (1759) extolled the martyrdom of the ensign vis-a-vis "le barbare homicide" by the English:

(45/46)

(45/46)

"Tremblantes aujourd'bui, pour conserver leurs jours /

De quelques alimens implorent les secours. /

Quel sort pour des héros! ô France! ô ma Patrie! /

Arme toi pour venger ta majesté flétrie."

(46/46)

De quelques alimens implorent les secours. /

Quel sort pour des héros! ô France! ô ma Patrie! /

Arme toi pour venger ta majesté flétrie."

(46/46)

(Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe; Christian A. Crouch, Nobility Lost; Joseph-Gaspard Chaussegros de Lery, Journal of Chaussegros de Lery, Pennsylvania Digital Library; Jacob-Nicholas Moreau, Memoire Contenant Le Precis Des Faits; Antoine-Léonard Thomas, Jumonville, ed. David A. Bell)

Thank you for reading!

@threadreaderapp Unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter