Today, 570 years ago, Ottoman Janissaries poured over the Theodosian Walls. The Genoese fled when their leader, Giovanni Giustiniani, was injured. The Emperor threw himself into the hopeless struggle & died with his men. After over 2,000 years, the Roman Empire was no more.

The final siege of Constantinople is the last chapter in the swan song of the Late Byzantine Empire & a dramatic tale of betrayal, duty, determination, honor, and horror.

In 1449, Emperor John VIII died & his brother Constantine XI took the throne. Crowned in a small ceremony in Mystras, Constantine was never coronated by the Patriarch in Constantinople thanks to his support for a Union with the Papacy, an unpopular movement in Byzantium.

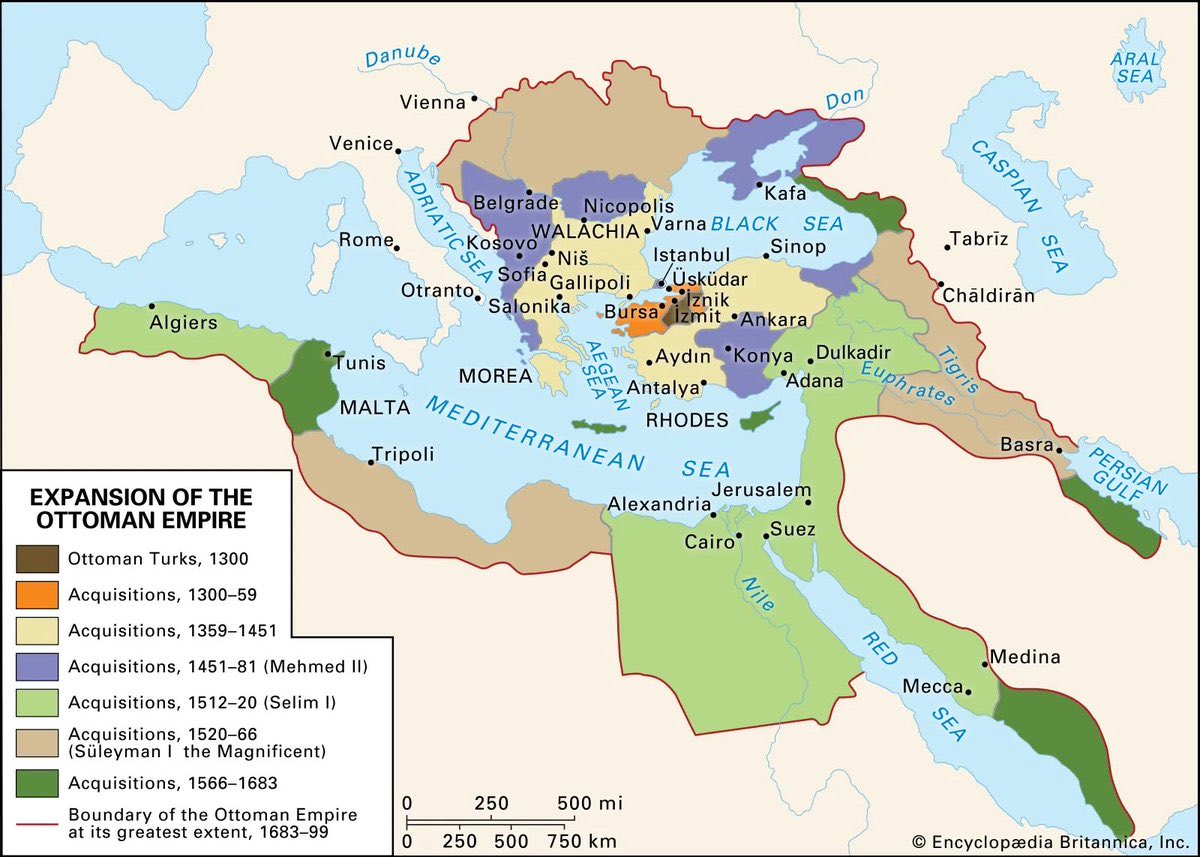

Constantine thought the Papal Union was necessary to secure military aid from the West. The Empire was in dire straits. With only the Peloponnese & some land just outside the City, the threat of the growing Ottoman Empire loomed large over the Byzantines.

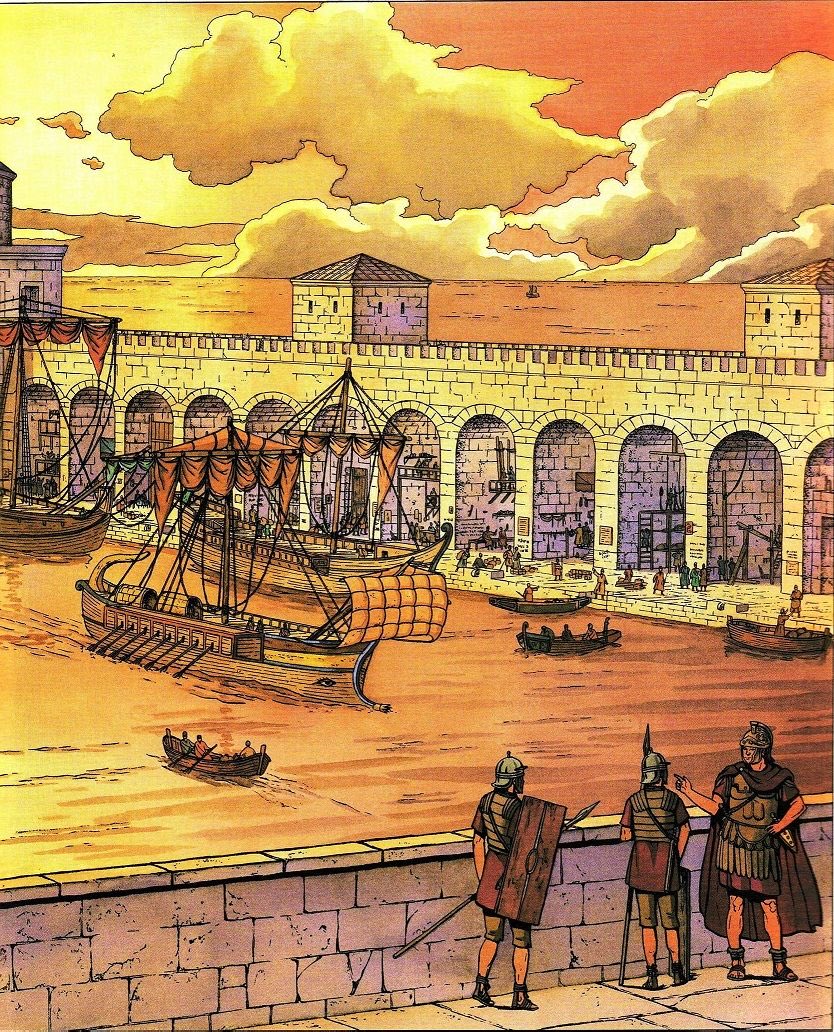

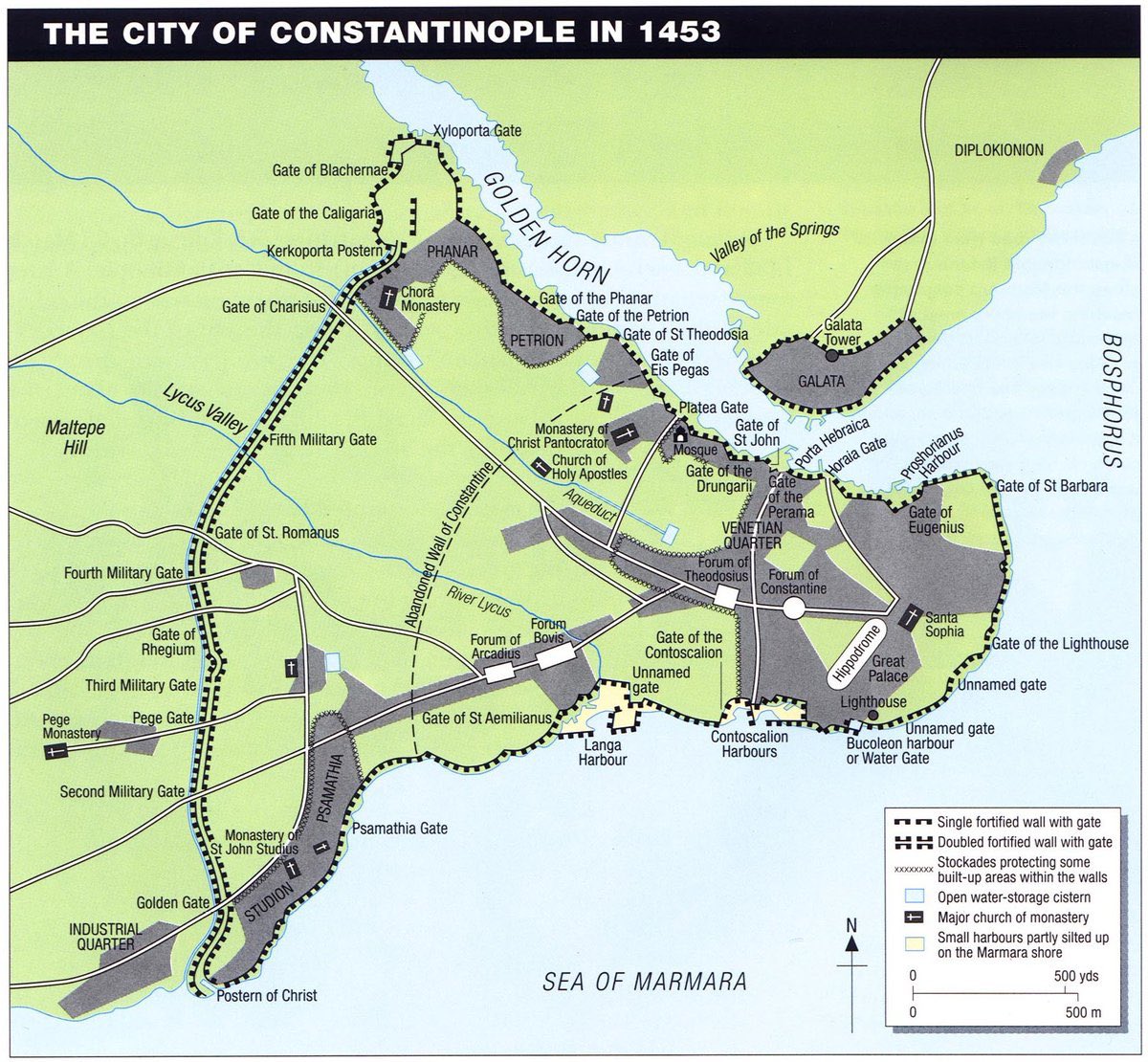

Constantinople, like the Empire, was much reduced. Only 50-70,000 people inhabited the once-sprawling metropolis. Orchards, fields, & ruins covered much of the City. The Theodosian Walls were much reduced from neglect.

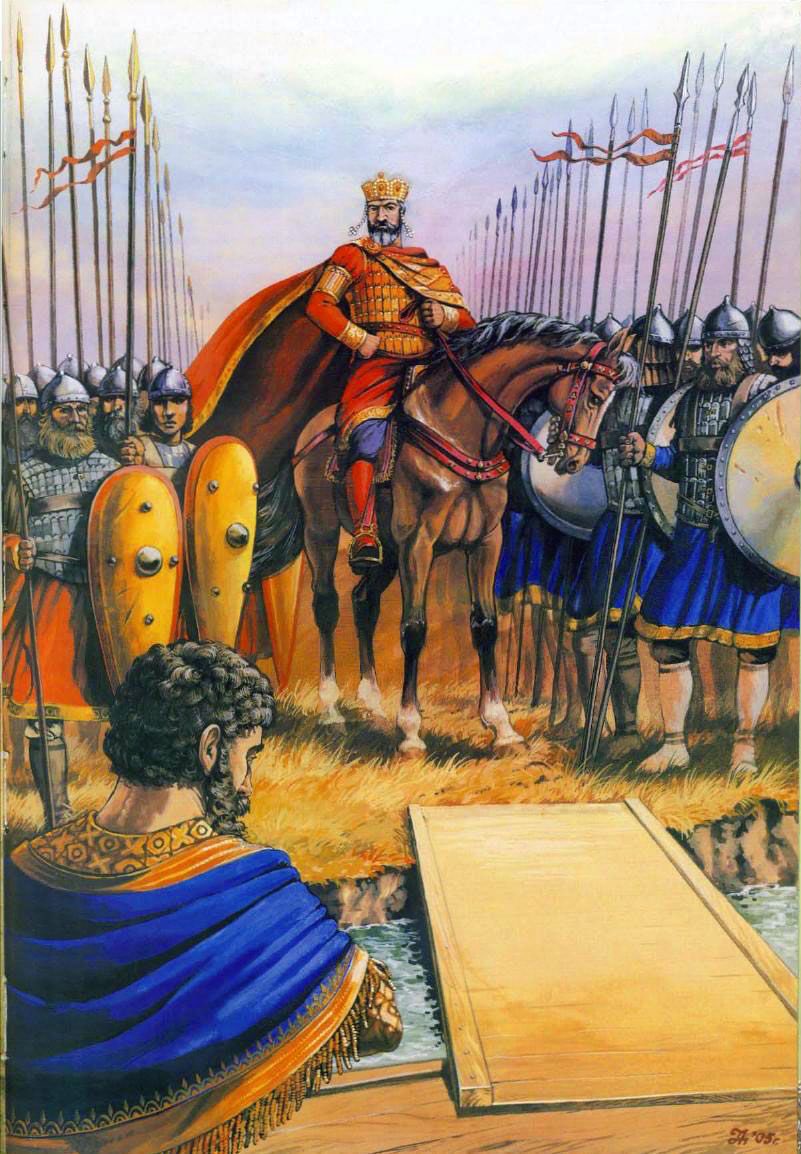

The 21-year old Mehmet II, tired of Byzantine meddling in Ottoman power politics & hell-bent on taking the Queen of Cities, threw himself into preparations for a brutal siege. Mehmet, in order to stop Western aid, built a great fortress on the Bosporus, “Strait Cutter.”

When a Venetian ship tried to pass without paying customs dues, the Ottomans sunk it with one cannon shot & killed the survivors. Constantine, recognized that he had no time to lose, forced the court to ratify the Union with the Papacy in an effort to secure lifesaving aid.

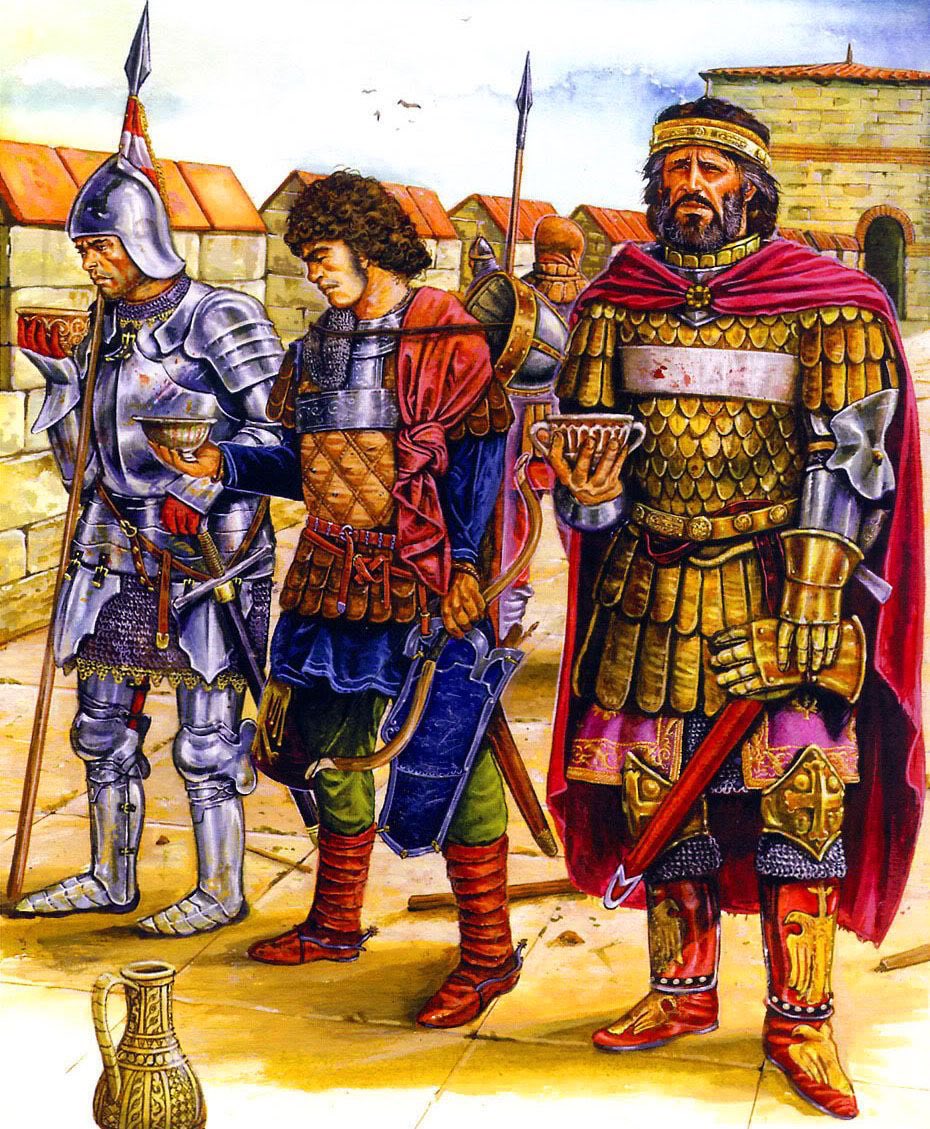

The West, however, was unenthusiastic. Funded by the Pope, Cardinal Isidore arrived with only 200 archers & funded some repairs on the city walls. Notably a contingent of fearsome Catalans & an Ottoman Prince & hostage, Orhan Celebi, with 600 Ottoman defectors joined the defense.

Constantine’s hope for substantial aid lay with Venice, which wasted precious time debating the issue. However, they let Constantine hire Cretan soldiers, famed in the Late Empire for their skill & loyalty. The Italian residents & sailors of the City decided to stay & fight.

From Genoa came the famous mercenary, Giovanni Giustiniani (Justin Justinian), an expert in defending cities. He brought 400 elite troops from Italy, 300 from Chios, & Johannes Grant, a German counter-mining expert. Constantine promised Giovanni Lesbos in return for his services.

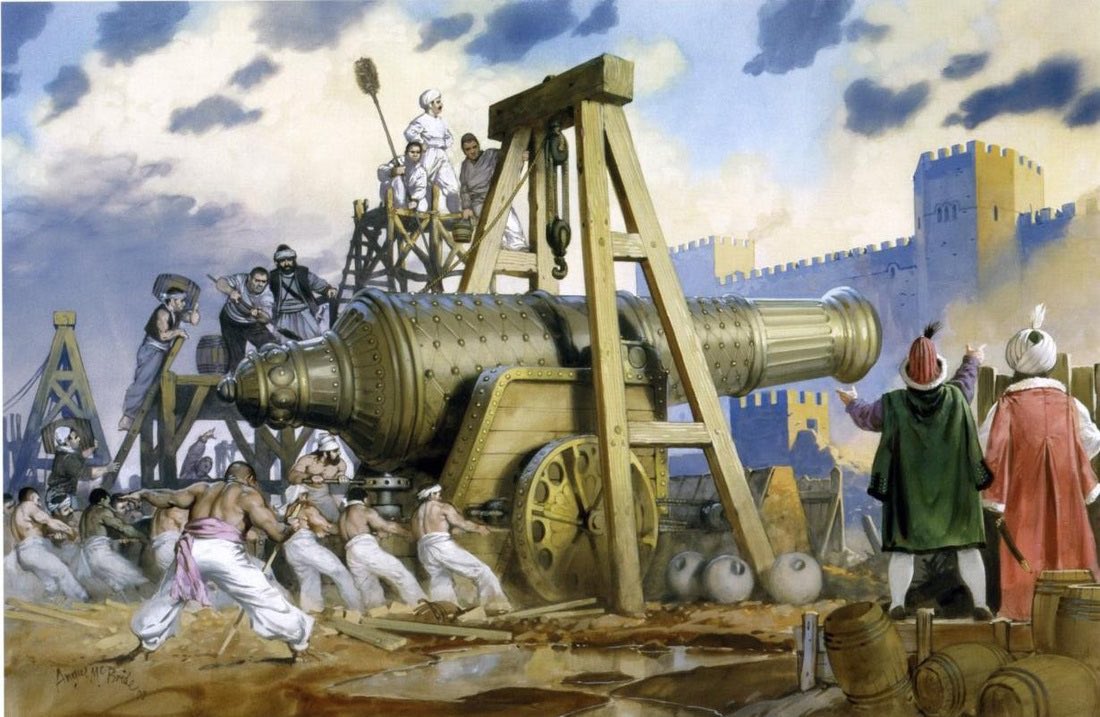

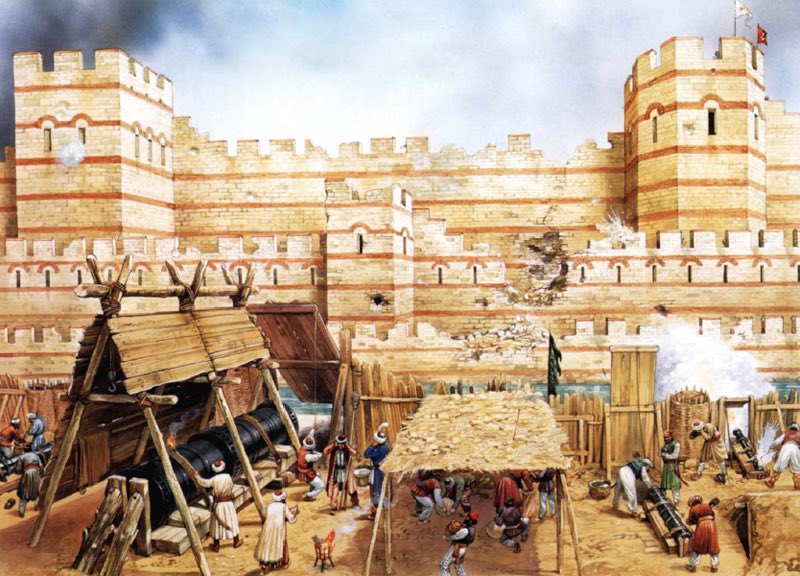

A Hungarian cannon-maker, Orban, offered his services to Constantine but was too expensive for the Empire. Orban turned to Mehmet & built him a massive cannon that could blast “the walls of Babylon itself.” 60 oxen & 400 men were needed to pull it.

Mehmet set out from Adrianople, his men building a road to Constantinople for his lumbering cannons. His best troops went to Byzantine redoubts & took them. For weeks Mehmet bombarded the walls with his cannon, every night the defenders would repair the damage, negating them.

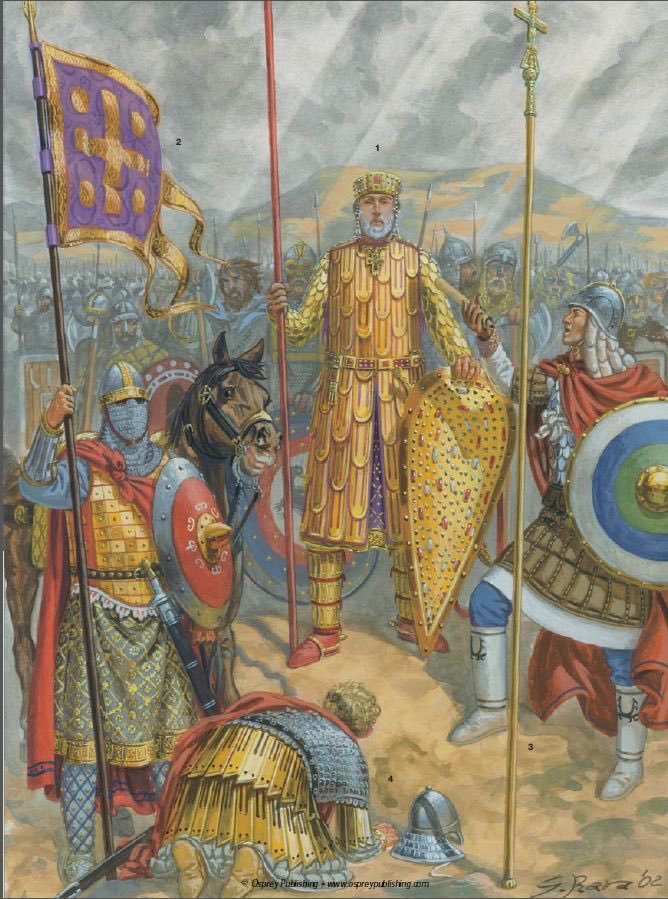

Mehmet’s assaults on the walls were repulsed with heavy losses. The skilled defense of the imposing Theodosian Walls by the Byzantine, Genoese, Cretan, and even Turkish soldiers stymied Mehmet’s plans even as the walls buckled under the bombardment.

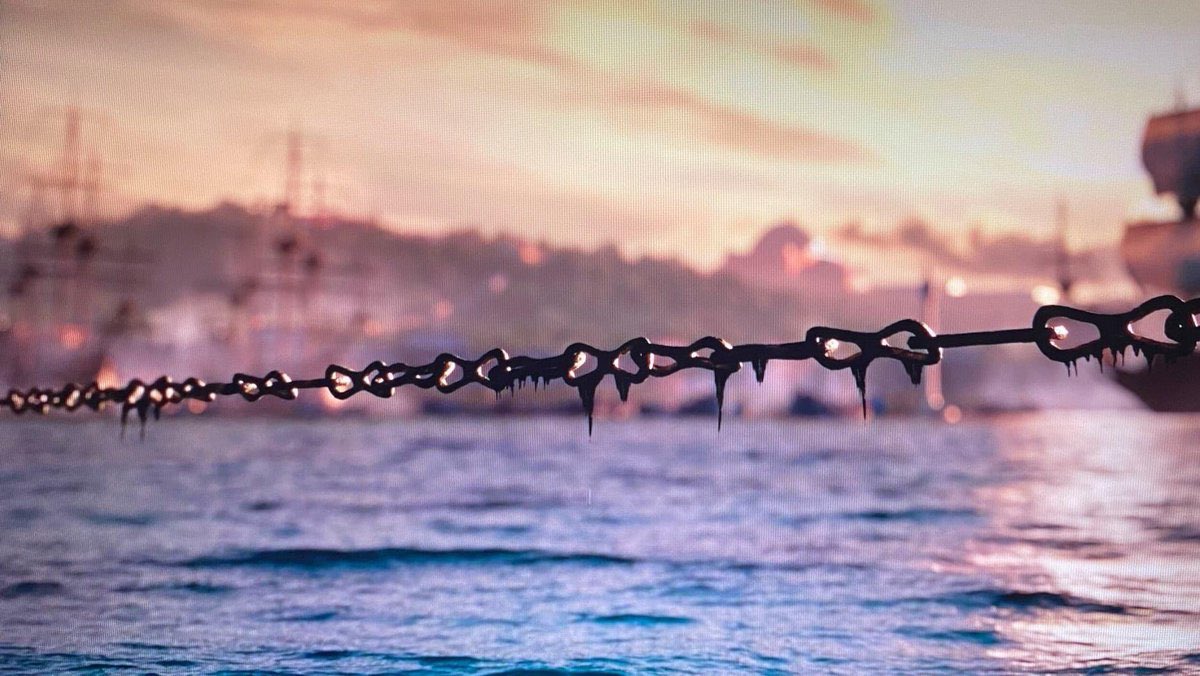

Hoping to stretch the defenders, the Ottoman fleet tried to enter the Golden Horn. However, an iron chain lay across the entrance. The Ottomans couldn’t destroy the chain & Mehmet whipped his admiral after four ships laden with supplies & troops ran the blockade into the harbor.

Mehmet would not be deterred. His army constructed a road of greased logs around the Genoese colony of Galata & pulled their ships across it & into the Golden Horn. This demoralized the Byzantines, now having to defend the weak Sea Walls & cut off from aid from Galata & beyond.

On the night of April 28th, the Byzantines sent fire ships toward the Ottoman fleet in the Golden Horn but were repulsed with heavy losses. The Ottomans continued to assault the walls to no avail. In mid-May Mehmet ordered tunnels be dug under the Theodosian Walls.

The Ottoman sappers were outmatched by Johannes Grant. He placed bowls of water along the walls to find the tunnels, counter-mining & collapsing them. On May 23rd two Turkish officers were captured & tortured. They revealed the locations of the last tunnels. Grant destroyed them.

Both armies grew desperate as the siege wore on & casualties mounted. Constantine dispatched ships to look for the Venetian fleet, but they returned, no fleet was coming. Some of Mehmet’s advisors, seeing the losses the young king had suffered, suggested he lift the siege.

Mehmet offered Constantine governorship of the Peloponnese & the safety of all in the City for his surrender. Constantine replied, “…it is not for me to decide or for anyone else of its citizens; for all of us have reached the mutual decision to die of our own free will.”

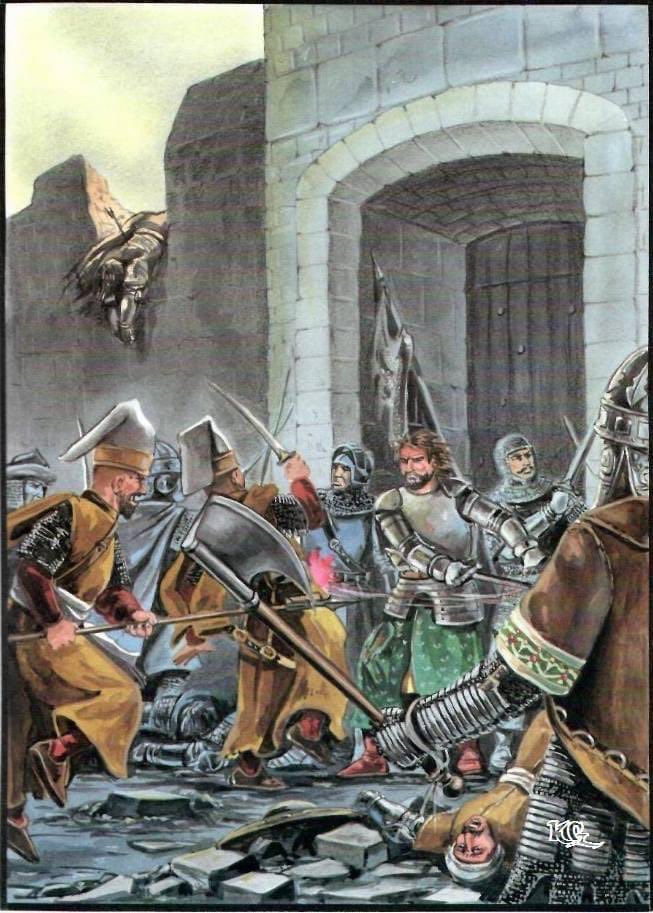

On May 28th the Ottomans prepared for the final assault. The defenders of the City, Latin & Orthodox worshipped together in the Hagia Sophia for Vespers the night before Pentecost. After midnight the assault began. Waves of irregular troops attacked the walls near the Blachernae.

None broke through until the Janissaries, the Ottoman elite, pushed over the walls. With Giustiniani wounded, the Genoese in retreat, & the Ottoman flag flying over the Kerkoporta (a small postern gate that was left unlocked), the defense collapsed.

Many fled to the ships, sought sanctuary in churches, or returned to their homes to protect their families. Constantine cried, “the City is fallen & I am still alive.” He then tore off his imperial regalia & led his men in one final charge. His body was never found.

For three days the Ottomans sacked the City, enslaving all they could find, massacring all who resisted or were too young or old to be of use. What treasures that survived 1204 were taken or destroyed by the attackers. Many hapless citizens barricaded themselves in Hagia Sophia.

The divine intervention they prayed for did not come to pass. The Ottomans broke in. Those of use were enslaved. The women were raped. Notably, Grand Duke Loukas Notaras's daughter was forced to lie on the altar with a crucifix under her head & gang raped by several Ottomans.

Mehmet didn’t want to raze his new capital & after the customary 3 days of looting, ended the violence. When he rode through the deserted & blood-soaked streets, past the broken buildings & ancient monuments, he cried, “What a city we have given over to plunder and destruction.”

Addendum: the Fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Middle Ages. Great thinkers & ancient works went West to sow the seeds of the Renaissance. Over 5,000 cannon balls shattered the Theodosian Walls, the greatest fortification in history, signaling the Age of Gunpowder.

The Ottoman Empire continued to expand to dominate the Balkans & Middle East & become a first rate power. Their control of the trade routes helping spark the Age of Discovery as Europeans sought new ways to the riches of the East.

Few of the men who defended the City survived. Giustiniani died of his wounds. Celebi, loyal to the end, was executed. Many Byzantine notables were executed, like Loukas Notaras, or fled West including much of the Palaiologos family.

Some Cretans put up such fierce resistance in three towers at the entrance to the Golden Horn that the Ottomans let them leave the City unharmed & with their arms.

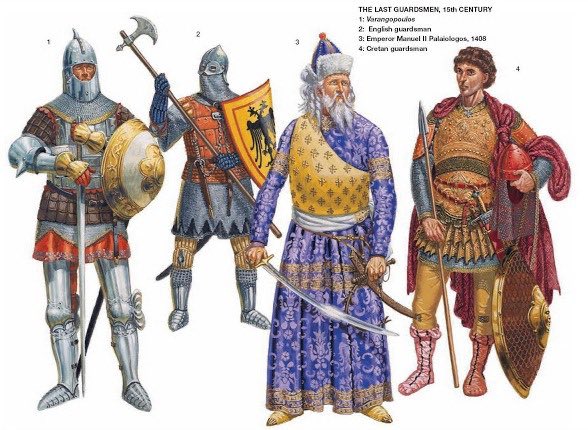

Some scholars, like Blöndal, believe these Cretans to be some of the last Varangian Guardsmen. By the late 13th century the Cretans had entered the Byzantine military in large numbers as elite troops, some possibly as Varangians as they partook in traditional duties of the Guard.

We also know that the Varangopouli (Varangians & their mixed descendants) are attested in Byzantine sources until the early 15th century, some bearing their famous axes. Although they are not mentioned in the 1453, it’s plausible they still acted as the Emperor’s bodyguard.

Accepting these two assertions, the Varangian Guard died with Constantine in his legendary last stand. Another contingent may have been the last Byzantine & Roman soldiers ever, fighting so heroically they left with their battlefield honors & pride as the Last of the Varangians.

Enjoy the thread? Sign up for the Substack! New articles will be published in the coming weeks.

varangianchronicler.substack.com

varangianchronicler.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter