"Deal of the Century": RJR Nabisco

In April 1989, KKR bought RJR for $30.8 billion. The deal was 6x larger than any other buyout and exceeded "the $29.5 billion cash value of the seven other biggest LBOs." It remained the largest buyout for eighteen years.

Here's the story...

In April 1989, KKR bought RJR for $30.8 billion. The deal was 6x larger than any other buyout and exceeded "the $29.5 billion cash value of the seven other biggest LBOs." It remained the largest buyout for eighteen years.

Here's the story...

It starts with RJR's CEO—Ross Johnson. By October 1988, Johnson had a solid three-year operating record:

+20% sales

+50% earnings

+66% EPS

The problem: RJR's stock price

"The company was going like gangbusters but the [stock] got beaten down."

Johnson's solution: An LBO

+20% sales

+50% earnings

+66% EPS

The problem: RJR's stock price

"The company was going like gangbusters but the [stock] got beaten down."

Johnson's solution: An LBO

Here's his LBO pitch to RJR's board:

"It's plain as the nose on your face that this company is wildly undervalued. We're sitting on food assets worth 22-25 times earnings and we trade at 9 times. We've studied ways of increasing value. I believe the only way is through an LBO."

"It's plain as the nose on your face that this company is wildly undervalued. We're sitting on food assets worth 22-25 times earnings and we trade at 9 times. We've studied ways of increasing value. I believe the only way is through an LBO."

But Henry Kravis had the same idea.

Kravis viewed RJR as the "ideal LBO" with "every characteristic that you could possibly look for," including:

- Tremendous branded products

- Stability of earnings

- Enormous cash flow

- Valuable standalone assets

- Attractive purchase price

Kravis viewed RJR as the "ideal LBO" with "every characteristic that you could possibly look for," including:

- Tremendous branded products

- Stability of earnings

- Enormous cash flow

- Valuable standalone assets

- Attractive purchase price

An "epic" bidding war ensued between Johnson and Kravis. "Everything on Wall Street stopped. It was like two gunfighters in the street. And everyone wanted to watch or pick up a gun."

- Opening bid: $75 a share (10/20/1988)

- Winning bid: $109 a share (11/30/1988)

- Opening bid: $75 a share (10/20/1988)

- Winning bid: $109 a share (11/30/1988)

BID #1 — 10/20/1988

Johnson: $75 per share

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $16.9 billion

- Enterprise value: $21.4 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 12.3X

- EV/EBIT: 7.5X

Johnson: $75 per share

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $16.9 billion

- Enterprise value: $21.4 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 12.3X

- EV/EBIT: 7.5X

BID #2 — 10/24/1988

Kravis: $90 per share

[$78 cash / $12 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $20.3 billion

- Enterprise value: $24.7 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 14.7X

- EV/EBIT: 8.7X

Kravis: $90 per share

[$78 cash / $12 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $20.3 billion

- Enterprise value: $24.7 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 14.7X

- EV/EBIT: 8.7X

BID #3 — 11/03/1988

Johnson: $92 per share

[$84 cash / $8 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $20.8 billion

- Enterprise value: $25.2 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 15.1X

- EV/EBIT: 8.8X

Johnson: $92 per share

[$84 cash / $8 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $20.8 billion

- Enterprise value: $25.2 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 15.1X

- EV/EBIT: 8.8X

BID #4 — 11/18/1988

Johnson: $100 per share

[$90 cash / $10 paper]

Kravis: $94 per share

[$75 cash / $19 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $21.2-22.6 billion

- Enterprise value: $25.6-27.0 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 15.4-16.4X

- EV/EBIT: 9.0-9.5X

Johnson: $100 per share

[$90 cash / $10 paper]

Kravis: $94 per share

[$75 cash / $19 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $21.2-22.6 billion

- Enterprise value: $25.6-27.0 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 15.4-16.4X

- EV/EBIT: 9.0-9.5X

BID #5 — 11/30/1988

Johnson: $112 per share

[$84 cash / $28 paper]

Kravis: $109 per share

[$81 cash / $28 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $24.6-25.3 billion

- Enterprise value: $29.0-29.7 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 17.8-18.3X

- EV/EBIT: 10.2-10.4X

THE WINNER: HENRY KRAVIS

Johnson: $112 per share

[$84 cash / $28 paper]

Kravis: $109 per share

[$81 cash / $28 paper]

Pricetag:

- Market cap: $24.6-25.3 billion

- Enterprise value: $29.0-29.7 billion

Multiples:

- P/E: 17.8-18.3X

- EV/EBIT: 10.2-10.4X

THE WINNER: HENRY KRAVIS

How'd Kravis win with the lower bid?

He agreed to a 'reset' clause.

Junk bonds comprised ~25% of both bids. RJR worried these "securities weren't worth anywhere near 100 cents on the dollar." So Kravis agreed to "'reset' mechanisms that guaranteed the bonds traded at [par]."

He agreed to a 'reset' clause.

Junk bonds comprised ~25% of both bids. RJR worried these "securities weren't worth anywhere near 100 cents on the dollar." So Kravis agreed to "'reset' mechanisms that guaranteed the bonds traded at [par]."

But after the deal closed, "the reset mechanism turned into a financial death trap." In January 1990, despite results "ahead of projections on virtually every measure," Moody's downgraded RJR. As RJR's bonds collapsed, Kravis scrambled to avoid a "reset at a rate of 25% or more."

Kravis faced another crisis: The price Wars

For the first time, low-priced cigarettes were taking share from premium brands. Philip Morris, the industry price leader, responded by cutting retail prices by 20% in one day. These price cuts "absolutely knocked the wind out of RJR."

For the first time, low-priced cigarettes were taking share from premium brands. Philip Morris, the industry price leader, responded by cutting retail prices by 20% in one day. These price cuts "absolutely knocked the wind out of RJR."

The one-two punch of RJR's…

- Reset bonds

- Price wars

…produced a 2.8% IRR for KKR.

RJR was also:

- Kravis's "largest investment"

- "Half of KKR's giant $5.6B fund"

This had a "severe impact" on returns.

KKR 1987 Fund IRRs

- Excluding RJR: 24%

- Including RJR: 14%

- Reset bonds

- Price wars

…produced a 2.8% IRR for KKR.

RJR was also:

- Kravis's "largest investment"

- "Half of KKR's giant $5.6B fund"

This had a "severe impact" on returns.

KKR 1987 Fund IRRs

- Excluding RJR: 24%

- Including RJR: 14%

Want to learn more about the RJR buyout? Check out these two books:

- Barbarians at the Gate

- Merchants of Debt

They're my two favorites on 1980s LBOs.

- Barbarians at the Gate

- Merchants of Debt

They're my two favorites on 1980s LBOs.

FOOTNOTE: PURCHASE PRICE

RJR purchase price:

+ $24.3 billion stock purchase

+ $4.9 billion assumed debt (net)

+ $1.6 billion deal fees and expenses

= $30.8 billion total purchase price

RJR purchase price:

+ $24.3 billion stock purchase

+ $4.9 billion assumed debt (net)

+ $1.6 billion deal fees and expenses

= $30.8 billion total purchase price

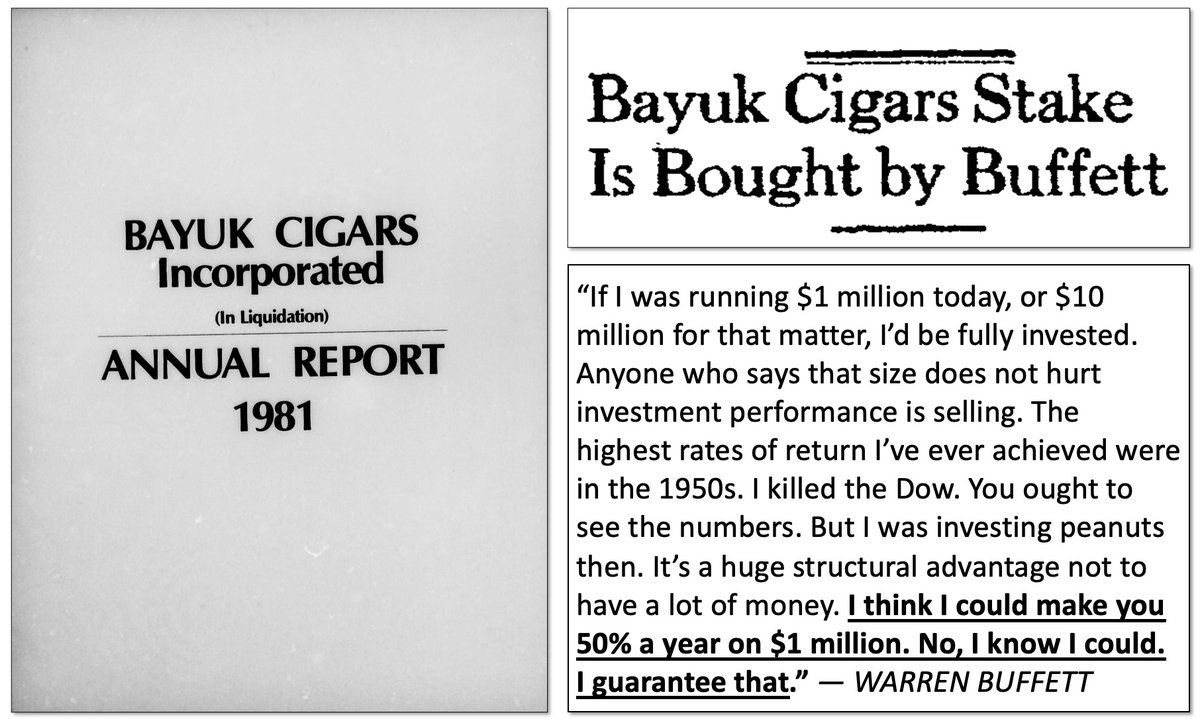

FOOTNOTE: BUFFETT BUYS THE DEBT

Buffett bought RJR's distressed debt in 1990. He paid ~67 cents for the exchangeable reset debentures. The bonds were called 1.5 years later.

[note: ~67 cents of par plus accrued]

Buffett bought RJR's distressed debt in 1990. He paid ~67 cents for the exchangeable reset debentures. The bonds were called 1.5 years later.

[note: ~67 cents of par plus accrued]

FOOTNOTE: BUFFETT ON THE LBO

Buffett blessed Salomon's minority commitment in the Johnson bid.

His remarks about cigarette economics:

- It costs a penny to make

- It sells for a dollar

- It's addictive

And there's fantastic brand loyalty.

Buffett blessed Salomon's minority commitment in the Johnson bid.

His remarks about cigarette economics:

- It costs a penny to make

- It sells for a dollar

- It's addictive

And there's fantastic brand loyalty.

FOOTNOTE: PRITZKER

The Pritzkers joined a longshot competing bid. Their $600 million investment would've made RJR "twice the largest commitment the family had ever made."

The Pritzkers joined a longshot competing bid. Their $600 million investment would've made RJR "twice the largest commitment the family had ever made."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh