American military veterans have a suicide problem.

Some have theorized the reason is deployment-related trauma.

Leveraging the random assignment of new soldiers to units with different deployment cycles, Bruhn et al. found that was wrong.

Deployment did not increase suicides.

Some have theorized the reason is deployment-related trauma.

Leveraging the random assignment of new soldiers to units with different deployment cycles, Bruhn et al. found that was wrong.

Deployment did not increase suicides.

Looking only at violent deployments (ones with peer casualties), there aren't noncombat mortality effects either.

What explains veteran suicide rates?

What explains veteran suicide rates?

The reason seems to be that the proposition is wrong: veterans do not have increased suicide risk.

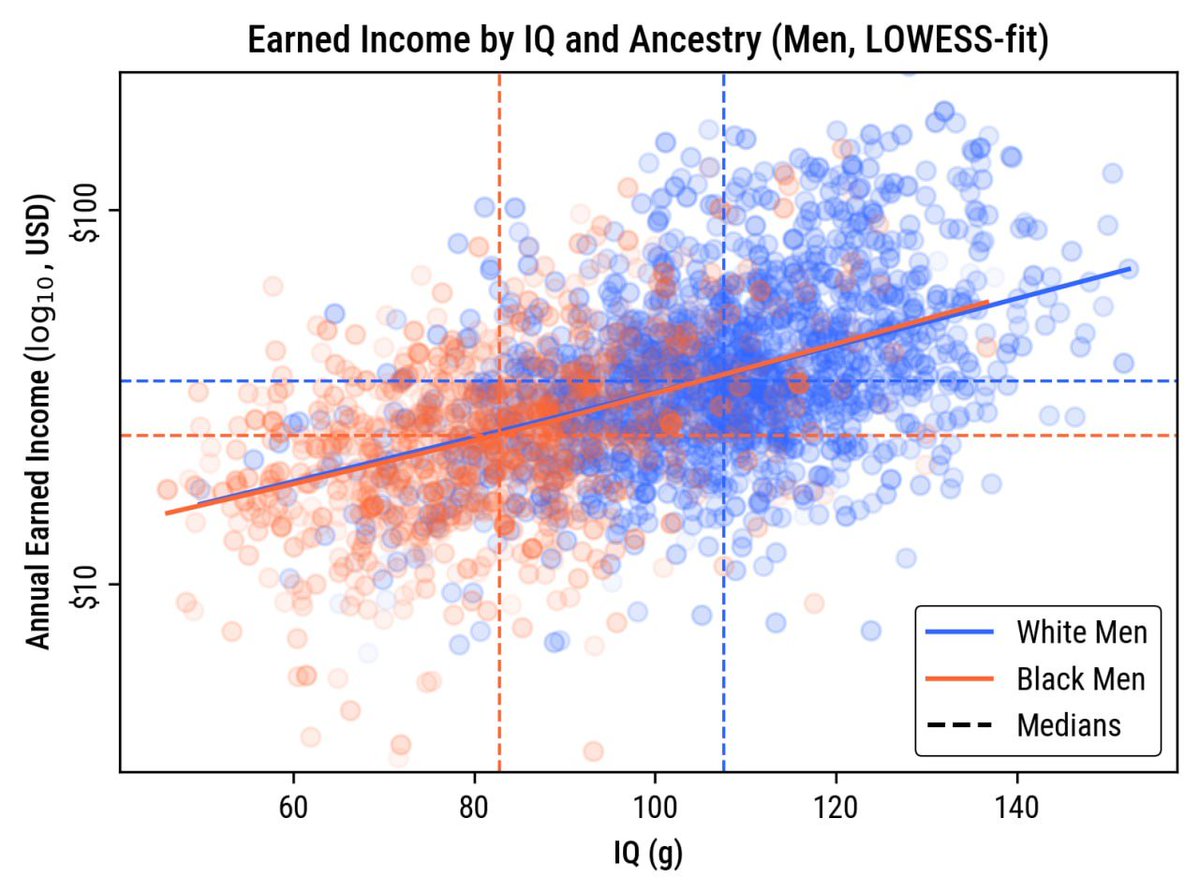

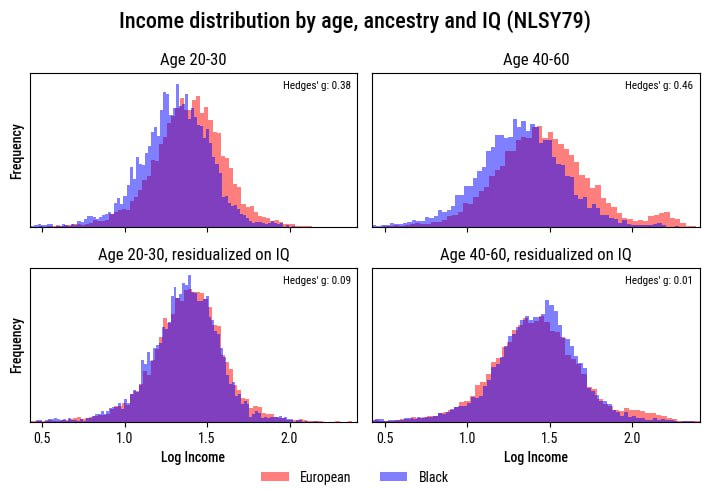

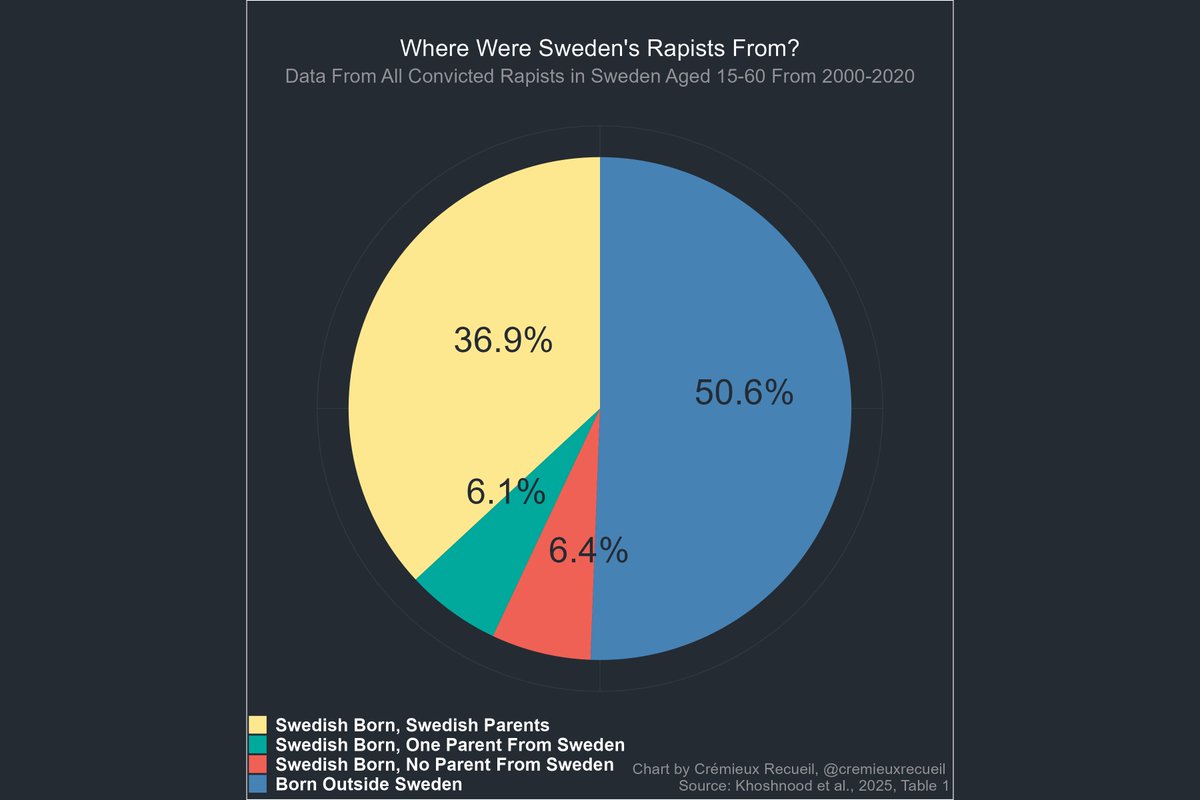

This may seem surprising, but it's not. Their suicide rates are elevated over the general population because most of them are young White men. That group has a suicide issue.

This may seem surprising, but it's not. Their suicide rates are elevated over the general population because most of them are young White men. That group has a suicide issue.

There are good and bad parts to this observation.

On the one hand, it means that there is not selection of suicidal people into the military.

On the other, demographic selection makes this problem into one that agencies like the VA will probably not be able to fix on their own

On the one hand, it means that there is not selection of suicidal people into the military.

On the other, demographic selection makes this problem into one that agencies like the VA will probably not be able to fix on their own

because it's not a soldier problem, it's a young White male problem.

I don't know how this can be fixed, but presumably tackling opiate use would help.

Soliman (2022) found that DEA crackdowns on overprescribing pharmacies resulted in fewer local suicide deaths.

I don't know how this can be fixed, but presumably tackling opiate use would help.

Soliman (2022) found that DEA crackdowns on overprescribing pharmacies resulted in fewer local suicide deaths.

Soliman also found that sanctioning specific doctors affected opioid-related mortality more generally without impacting suicide rates. Effects were generally larger for males than females and they were larger for people aged 30-49 than those aged 15-29 or 85+. No race data.

Kennedy-Hendricks et al. found that Florida's pill mill crackdown reduced opioid overdose mortality considerably.

Their supplement contained details on the characteristics of the people who died from opioid overdoses, but I wasn't able to access it.

Regardless, this problem can

Their supplement contained details on the characteristics of the people who died from opioid overdoses, but I wasn't able to access it.

Regardless, this problem can

probably be helped to some degree.

Sources:

nber.org/papers/w30622

fivethirtyeight.com/features/suici…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.21…

More:

bfi.uchicago.edu/insight/resear…

Sources:

nber.org/papers/w30622

fivethirtyeight.com/features/suici…

papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cf…

ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.21…

More:

bfi.uchicago.edu/insight/resear…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh