In 🇪🇬 Egypt 🇪🇬 in May 2023, I came across an English Qur’an translation that appeared at first glance to be a reprint of an old work but, as is often the case, at second glance turned out to be much more than that. #qurantranslationoftheweek

Right next to the entrance of the Ibn Tulun Mosque, one of the major Islamic tourist sites of Cairo, stood a big shelf that offered ‘free Islamic books’ in a variety of languages.

These were predominantly Qur’an translations, most of them published by the Cairo-based Jamʿiyyat Ḥusn al-Qawl, variably translated to English as ‘Best Speech Society’ or ‘The Best of Speech Society’ (best-speech.org/books-library/).

The English section contained ‘The Meaning of the Glorious Qur’an’ by the famous British convert to Islam Marmaduke Pickthall (1875–1936). Pickthall’s translation was first published in London in 1930.

Using it as the basis of a reprint seems like an obvious choice for a daʿwa publisher since the translation is generally considered respectable by Sunni Muslims, was written by a native speaker of English and is free of copyright protections today.

Pickthall had written his Qur’an translation while in the service of the Nizam of Hyderabad in India and had worked with an Egyptian scholar to revise it and ensure its accuracy before it was published.

It was his goal to present his readers with ‘the first English translation of the Qur’an by an Englishman who is a Muslim,’ ‘with a view to the requirements of English Muslims.’

He believed the existing English translations by non-Muslim Orientalists to be often offensive to Muslims, and practically all existing English translations to be stylistically ‘unworthy’ of the Qur’an.

He aimed for a style that brought across the gravity and majesty of the Qur’an. Many readers were impressed with the result while some considered it somewhat pompous.

Like all translators of his time, Pickthall used an archaic form of English modelled after the early modern ‘King James Bible,’ which resulted in translations such as:

‘Lo! We have given thee Abundance; So pray unto thy Lord and sacrifice’ (Q 108:1–2).

‘Lo! We have given thee Abundance; So pray unto thy Lord and sacrifice’ (Q 108:1–2).

Looking inside the edition of Pickthall’s work that I picked up at the Ibn Tulun Mosque, the editor’s note makes it clear that, in fact, this is a heavily revised edition of Pickthall’s translation.

The editor, one Khaled Mohammad Fahmy, argues that Pickthall’s archaic English might make it hard for the reader to understand the meanings of the Qur’an, even if it is better-suited to conveying its resonance and rhythm.

Therefore, he replaced all archaic and ‘unfamiliar literary’ vocabulary and structures with modern English. This already involves a rather large-scale interference with Pickthall’s original text.

But on top of this, and maybe more interestingly, Khaled Mohammad revised Pickthall’s translation for ‘accuracy’ in terms of ʿaqīda (creed, doctrine).

To achieve this, he writes, he drew on Qur’anic commentaries as well as a motley collection of English Qur’an translations by translators with widely divergent ideological and institutional backgrounds:

Yusuf Ali, Hilali/Khan, Saheeh International, Maulana Muhammad Ali, Muhammad Abdel-Haleem, Muhammad Asad, T.B. Irving, Talal Itani and Mustafa Khattab.

Khaled Mohammad has made changes to both Pickthall’s language and his exegetical choices in practically every verse.

Khaled Mohammad has made changes to both Pickthall’s language and his exegetical choices in practically every verse.

The changes he made are nearly always at the word level only, replacing a specific term with a different one. In doing so, he usually aimed for choosing the most mainstream Sunni translation possible, from a contemporary perspective.

For example, Pickthall’s ‘Scripture’ for ‘kitāb’becomes ‘book’ throughout, ‘flying creatures’ for ‘ṭayr’ become ‘birds’ (Q 105:3), ‘submissive to Allah’ becomes ‘Muslims [submissive to Allah]’, and ‘drop (of seed)’ becomes a ‘sperm-drop’ (Q 23:13).

A particularly interesting case is that of ‘taqwā’ and its derivates, a notoriously difficult term to translate. Pickthall decided to render it in different ways depending on context. So does Khaled Mohammad, but he is consistently at odds with Pickthall’s choices:

‘restraint from evil’ → ‘righteousness’ (Q 7:26)

‘duty’ → ‘piety’ (Q 5:8)

‘devotion’ → ‘piety’ (Q 22:37)

‘Observe your duty to Allah’ → ‘Fear Allah’ (Q 5:8; similarly Q 39:10; 10:63)

‘those who ward off (evil)’ → ‘those who fear Allah’ (Q 2:2, similarly Q 7:96)

‘duty’ → ‘piety’ (Q 5:8)

‘devotion’ → ‘piety’ (Q 22:37)

‘Observe your duty to Allah’ → ‘Fear Allah’ (Q 5:8; similarly Q 39:10; 10:63)

‘those who ward off (evil)’ → ‘those who fear Allah’ (Q 2:2, similarly Q 7:96)

In some cases, the editor’s changes do indeed facilitate understanding, for example when he replaces Pickthall’s somewhat strange rendering of ‘al-ākhira’ as ‘the latter portion’ with ‘the Hereafter.’

In other cases, it seems as if Khaled Mohammad simply wanted to leave a mark, such as when he translates ‘wa l-ʿaṣri’ (Q 103:1) as ‘By the time’ rather than Pickthall’s ‘By the declining day’ or ‘muṣliḥūn’ (Q 2:11) as ‘reformers’ rather than ‘peacemakers.’

Such choices might conform to the editor’s preference and might be in line with a certain trend, but in neither of these instances was Pickthall’s preference hard to understand or uncommon, let alone unacceptable.

Khaled Mohammad tried to adapt Pickthall’s translation to contemporary sensitivities; e.g., Pickthall had translated the instruction ‘wa ḍribūhunna’ in Q 4:34, addressed at husbands, as ‘and scourge them’ which the editor changed to ‘and beat them [lightly, if it is useful].’

That despite these extensive revisions Khaled Mohammad relied on Pickthall, rather than producing his own translation, is likely due to the fact that he is not a native speaker of English and his mastery of English seems, in fact, to be rather limited.

This is obvious from the problems that occur in cases where the changes he made to Pickthall’s translation go beyond the word level.

For example, Khaled Mohammad’s revision of Pickthall’s translation of the first segment of Q 1:7 (‘The path of those whom Thou hast favoured’) produced this result:

‘The path of those whom You have bestowed favour’

‘The path of those whom You have bestowed favour’

This is an incomplete and grammatically incorrect sentence in English because Khaled Mohammad, apparently, did not know that the verb ‘to bestow’ requires a preposition.

His lack of fluency in English might have been the reason he felt the need to use such a broad range of existing translations to pick and choose his amendments from.

And it is most likely for the same reason that he left Pickthall’s notes and introduction (which he drew from a version that was already slightly ‘rectified’ by a previous editor) alone.

Here, he could not rely on other works that would have helped him make alternative textual choices, and it is noticeable that there is no interference even in cases where Pickthall’s notes might be considered somewhat problematic by an editor aiming for ‘doctrinal correctness.’

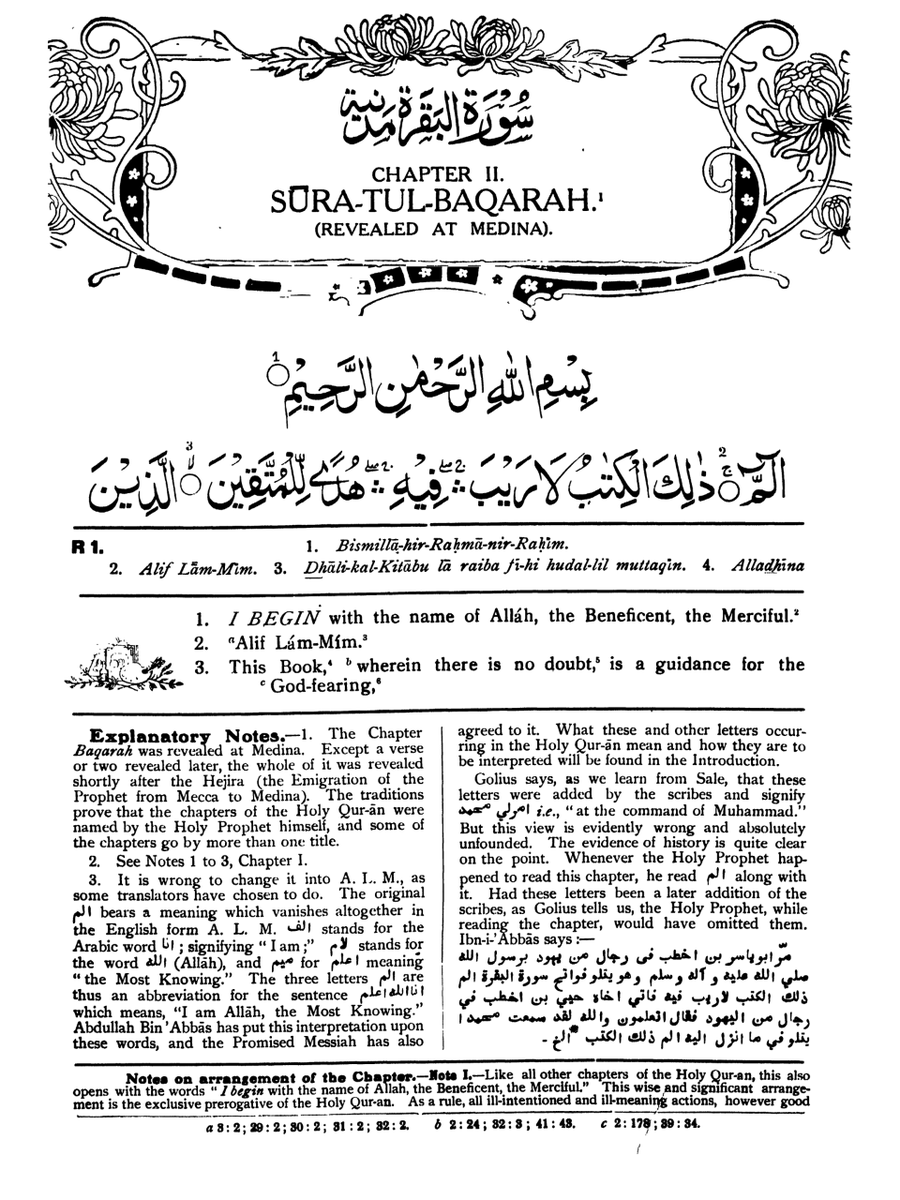

For example, Pickthall says of the disjointed letters at the beginning of many suras that, according to the ‘prevalent opinion,’ they ‘indicate some mystic words.’

This comes rather close to the opinion of Ahmadiyya translators who, for example, rendered ‘alif lām mīm’ as ‘I am Allah, the best Knower’ (Muhammad Ali, 1917) – they were not entirely alone doing so, but it is hardly the prevalent opinion.

Even more controversially, Pickthall adds the remark that according to a different opinion, the disjointed letters are merely the initials of a scribe, which is a theory that was advanced by non-Muslim Orientalists.

It was not shared by Muslims at all because it would mean that the disjointed letters are not part of the revealed text.

Still, Khaled Mohammad did nothing to change this note, even though it could be considered much more problematic than many of Pickthall’s word choices that he ‘rectified.’

In a few cases, Pickthall consciously made unconventional choices because he wanted to bring across the specificity of a particular Islamic concept.

Moreover, the conventions, in his time, were largely determined by the translations of Orientalists who he thought had not captured the nuances of the concept in question.

The best example of this is the term ‘ṣalāt,’ which previous Orientalist Qur’an translations into English had all rendered as ‘prayer.’

This was a somewhat ambiguous translation because it would likely be taken by Christian readers to mean something like the Christian prayer, which would be called ‘duʿāʾ’ in Arabic, rather than ‘ṣalāt.’

Therefore, Pickthall used the term ‘worship’ to render ‘ṣalāt.’

Therefore, Pickthall used the term ‘worship’ to render ‘ṣalāt.’

But Khaled Mohammad, possibly considering it an inaccurate translation and unaware of the semantic considerations justifying it, replaced this with ‘prayer,’ thereby returning precisely to the Orientalist conventions that Pickthall wanted to avoid.

The ‘Best of Speech’ edition of Pickthall’s ‘The Meaning of the Glorious Qur’an’ shows the extent to which Qur’an translations travel, are being used, reworked and rewritten today.

Editors benefit from the fame of the author and his superior knowledge or his linguistic skills while inserting their own opinions and preferences into the texts.

On the one hand, this might seem like an oddity, and even a form of plagiarism in a world with a strong concept of individual authorship that places great store in originality.

On the other hand, it is, after all, not all that different from the way the tafsīr tradition has always worked: as a constant stream of commentary and metacommentary with continuous selections, amendments, additions, and subtractions. ~ JP ~ #qurantranslationoftheweek

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter