#HistoryKeThread: Waruhiu’s Last Bow

________

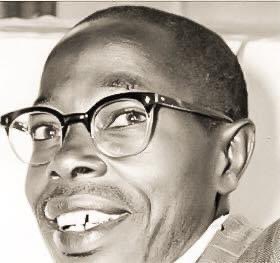

From September 1952, colonial chief of the Agikuyu in Kiambu, Waruhiu Kung’u - seen here addressing his last public rally at Kirigiti on 25th August of the same year, began transferring property to his wife and children.

📷:NMG

________

From September 1952, colonial chief of the Agikuyu in Kiambu, Waruhiu Kung’u - seen here addressing his last public rally at Kirigiti on 25th August of the same year, began transferring property to his wife and children.

📷:NMG

The Kirigiti rally had been organized by local (Kiambu) and Kenya Africa Union (KAU) leaders led by Waruhiu and Jomo Kenyatta respectively, to denounce Mau Mau.

In the run up to the address, there had been an increasing spate of violence meted out on collaborators, notably crown witnesses or police informers, church leaders, headmen and chiefs.

As Mau Mau fighters continued carrying out macabre killings, Waruhiu’s wives and close kin became concerned about his safety. Indeed, Waruhiu had himself received a number of death threats.

Some of them were handwritten notes that when not placed along paths leading to his homestead, were tucked in bodies of badly mutilated or decapitated dogs or cats found close to his home in Kiambu.

On 18th August 1952, which was exactly a week before the Kirigiti rally, he called on Kiambu District Commissioner Mr. Noel F. Kennaway and informed him that he feared for his life.

When the DC offered Waruhiu a bodyguard, the chief turned the proposal down, saying that he did not want to create an impression that he was scared of Mau Mau.

It was then that the DC directed the head of the local police division to issue Waruhiu with a .38 Smith & Wesson revolver and ammunition for his protection.

Waruhiu also took other measures. Occasionally he would spend the night in the home of the leader of the local settler community, Hugh T. Wells, at his farm in Cianda. He also avoided dining with strangers, or using the same road twice on any day.

On the day of the Kirigiti rally, which was attended by an estimated 30,000 people, anti-riot police from Nairobi were deployed to back up local Kiambu police. The colonial administration also seconded a film unit from the African Information Service to record the rally.

On this day, Jomo Kenyatta was not even a star attraction. The “keynote speaker” was none other than Chief Waruhiu, who was “dressed impeccably as always in a Western suit”, as Harry Thuku would later describe his appearance.

Other leaders who spoke at the rally included Kenyatta, Chief Josiah Njonjo, Chief Muhoho and Chief Koinange.

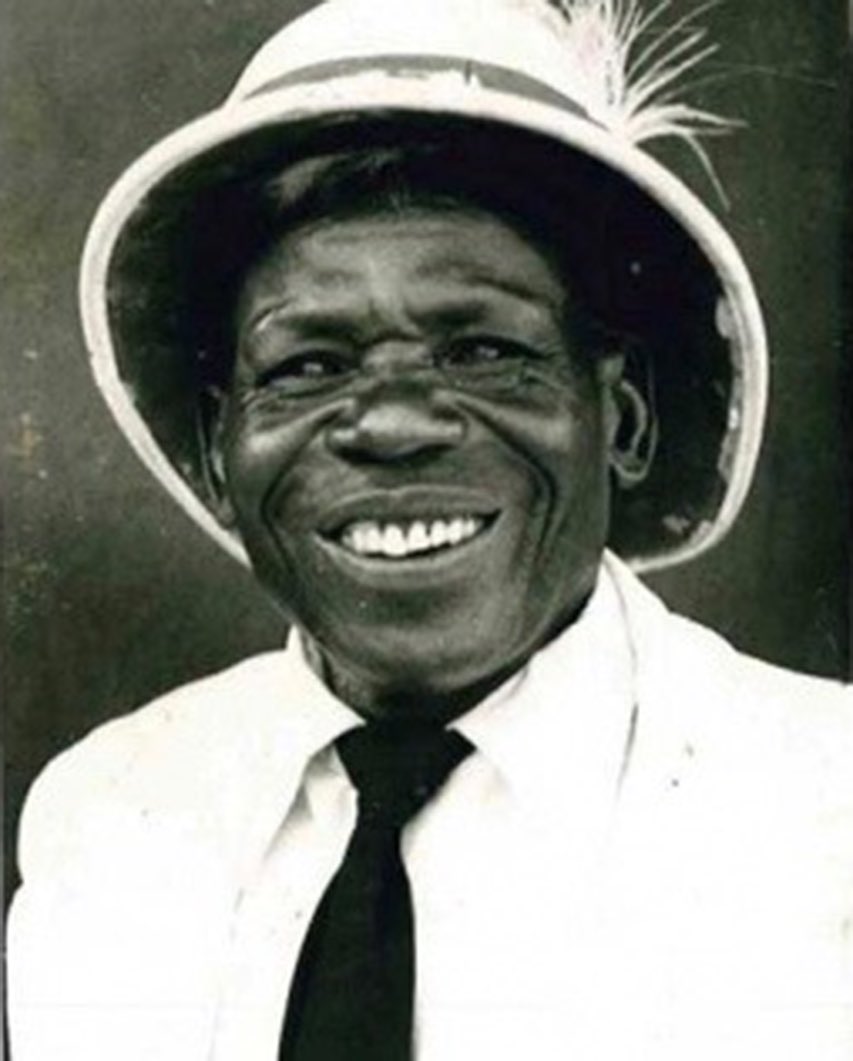

Leaders at the rally. L-R: James Gichuru, Waruhiu, Koinange, Eliud Mathu, Kenyatta, Njonjo and Muhoho.

When he rose to speak, Waruhiu, who looked pensive throughout the rally, held out a tuft of reeds and showed it off to the crowd.

“The Kikuyu country is like this grass, blowing this way and that way in the breeze of Mau Mau”, he began. “We denounce this Movement and declare that we do not want it”, he added.

He then held a solid stem of a wooden pole and said “by having nothing to do with Mau Mau, our country will be as steady as this pole”.

All leaders who spoke denounced #MauMau.

On his part, Kenyatta disclaimed any association between KAU and Mau Mau.

At one point, the rally nearly turned riotous. Chief Njonjo was angrily heckled when he said Africans were not ready for self-government as they “did not know how to manage their own affairs…”.

At one point, the rally nearly turned riotous. Chief Njonjo was angrily heckled when he said Africans were not ready for self-government as they “did not know how to manage their own affairs…”.

A section of the crowd walked out of the rally and it took Kenyatta’s charm to calm matters down and restore the meeting to order.

Weeks after the rally, and amid a rise in threats on his life, Waruhiu began allocating his vast estate to his wives and children. He seemed to have accepted that the threats on his life were real, and that his demise was around the corner.

⚠️Graphic images in the following tweets.

As he braced for the unknown, Mau Mau violence went on unabated. Chief Muhoya and his counterpart Chief Ignatio Ndung’u of Murang’a survived assassination attempts.

There were many cases of cattle belonging to loyalists or settler farmers having been maimed or disemboweled.

There were many cases of cattle belonging to loyalists or settler farmers having been maimed or disemboweled.

In September of 1952, Limuru Headman Nderu vanished without trace, never to be seen again. On 7th October 1952, unknown individuals ambushed Waruhiu as he rode in a car and shot him dead.

Even in his death, he was resplendently dressed.

Less than two weeks later, the colonial government, shocked by the killing, declared a State of Emergency. Mau Mau were undaunted. Three days later, they hacked Chief Nderi to death. There were similar macabre deaths of collaborators in Murang’a, Nyeri, Kirinyaga, Meru and Embu.

In concluding, these are the scenes from Waruhiu’s burial. Among the mourners was Jomo Kenyatta, who just weeks before stood alongside Waruhiu to condemn Mau Mau.

Strangely, Jomo Kenyatta was days after the burial arrested, and subsequently framed, for “managing Mau Mau”.

The murders of Chiefs Waruhiu, Nderi and Nderu featured prominently in a lead story on the Mau Mau in the globally acclaimed LIFE magazine.

Describing the fear with which settler farmers in central Kenya lived among Mau Mau, the magazine also featured the photo of a Thomson’s Falls white settler, John Wellings, bathing, his revolver placed on the soap dish as a safety precaution.

These stories are prepared by volunteers. If you enjoy them, kindly send a donation to MPESA Paybill 222 111 and Account No. 1947944.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter