Must-read case study on how we went from discovering key enabling technologies to being behind in the battery race.

Some key takeaways …

Some key takeaways …

https://twitter.com/gablova/status/1666781014511820800

▪️ We have a world-class university system that can consistently make breakthrough discoveries

Driven by ability to attract talented immigrants

Our scientific and research capabilities at the university-level are second to none

Driven by ability to attract talented immigrants

Our scientific and research capabilities at the university-level are second to none

▪️ We are not world-class at commercialization

China is relentless at commercialization

Who is our MITI?

China is relentless at commercialization

Who is our MITI?

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1665788282087649281

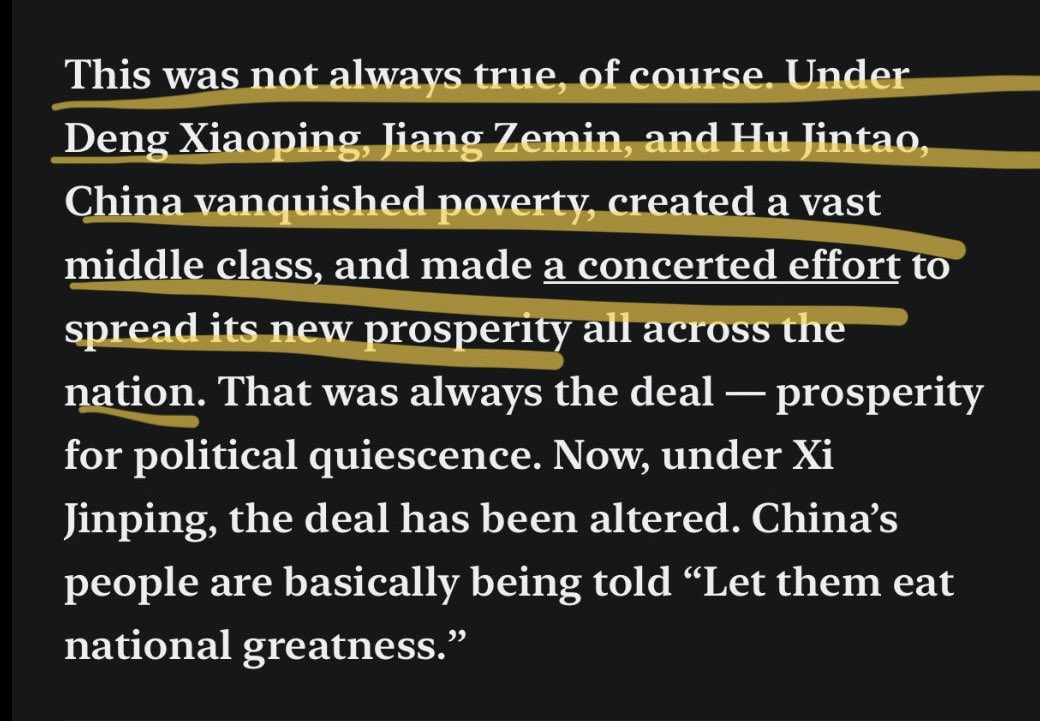

This has proven to be extremely shortsighted.

IBM "I think there's a world market for maybe five computers” vibes

IBM "I think there's a world market for maybe five computers” vibes

Are polarized politics going to get in the way, again?

Both sides are at fault here!

Both sides are at fault here!

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1666485498053812246

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh