How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/2020348532440592801Recently enacted policies like RPS now mandate a minimum amount of renewables-source power for heavy industry.

https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1943569358170787929

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1997351102954586128(1) Robin's chart doesn't have a source, and I don't know how he's calculating 65%.

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1991004398093545600

Gini coefficient for wages peaked in 2008.

Gini coefficient for wages peaked in 2008.https://twitter.com/glennluk/status/1837929183541866563

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1984619928649875737To prove his "transshipment" hypothesis at this level, Robin needs to provide more than just unsupported assertions.

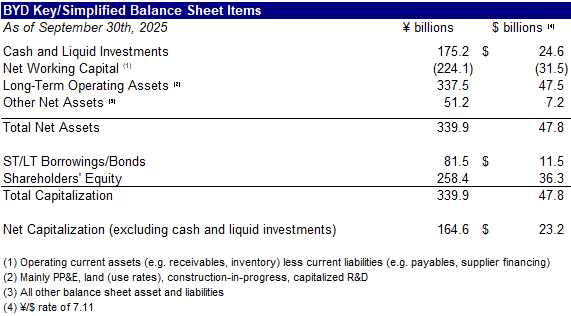

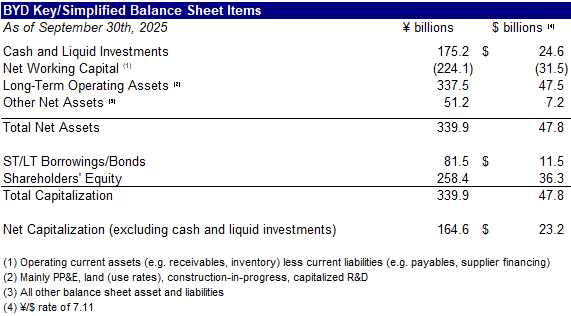

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1983939382156443991A better approach is to consider how much long-term capital the company has raised an compare it to the scale of operating capacity that capital has enabled.

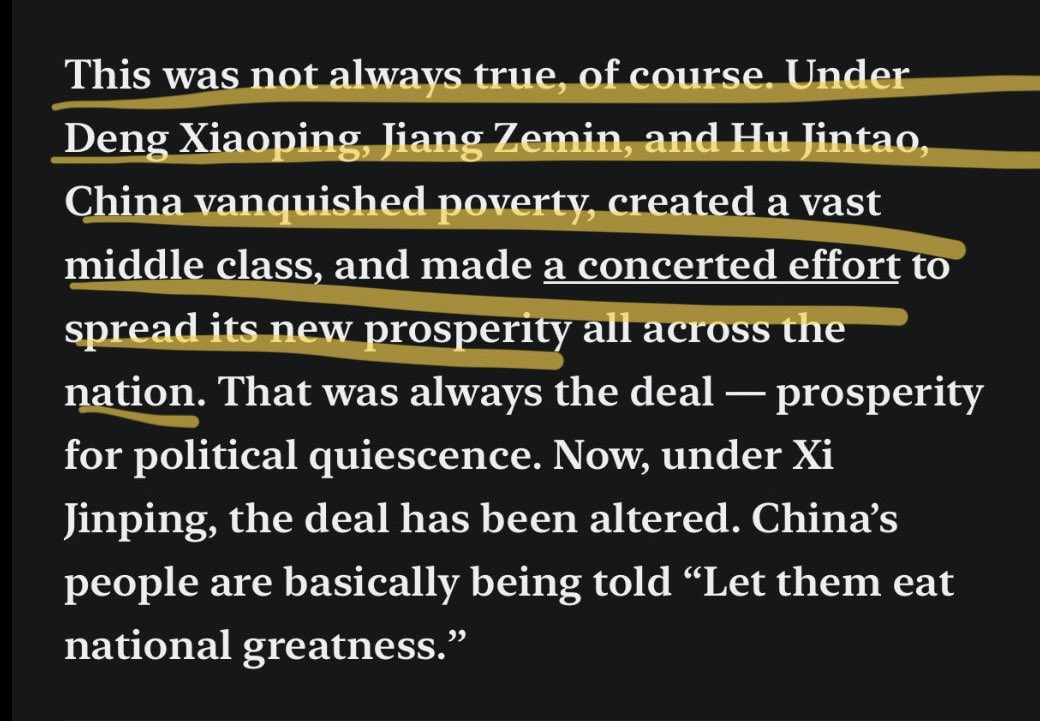

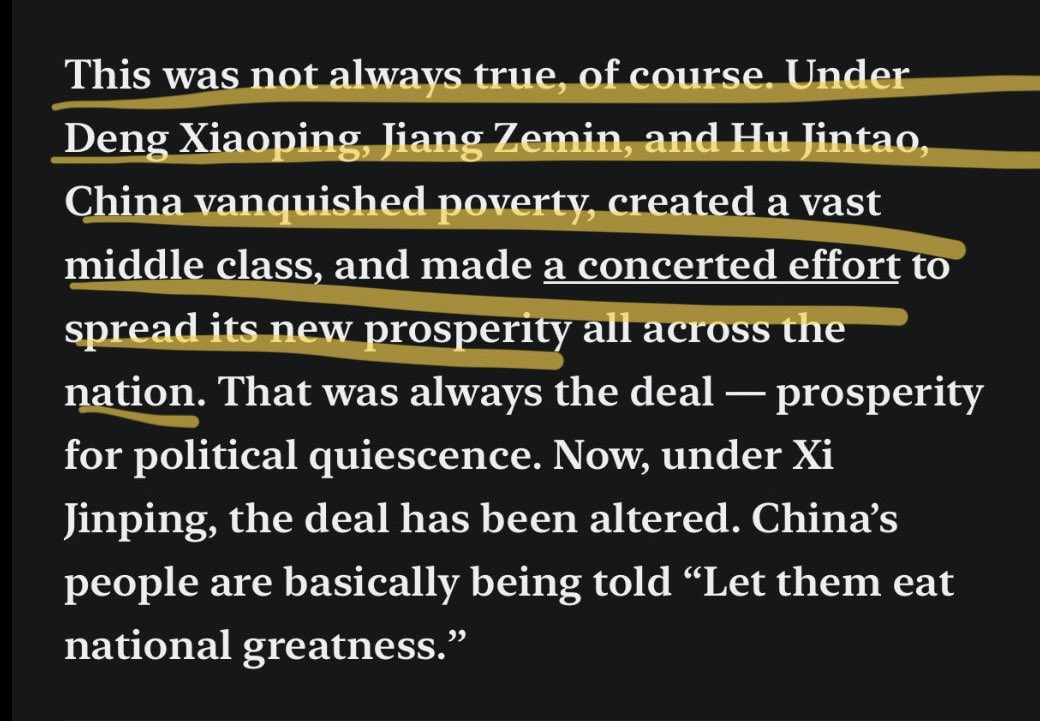

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1983788230538600474The problem with the "China does not spend enough on social welfare" narrative-pushers is in part a data one.

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1803110717748355172

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1981365280895861126Property and infrastructure development were two of the key economic development priorities from the mid-2000s to the early 2020s.

https://twitter.com/wstv_lizzi/status/1981297175813345745This is important because there is a group of people that insist on confusing/conflating demand with consumption in the China context.

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1765053195527610863

https://twitter.com/TheStalwart/status/1980926499177017677That China does not license IP is not an "indictment", it's a statistical quirk that requires some deeper understanding of the BoP and how it maps against real-world trade and investment realities.

https://x.com/stevehou0/status/1980963750489587850

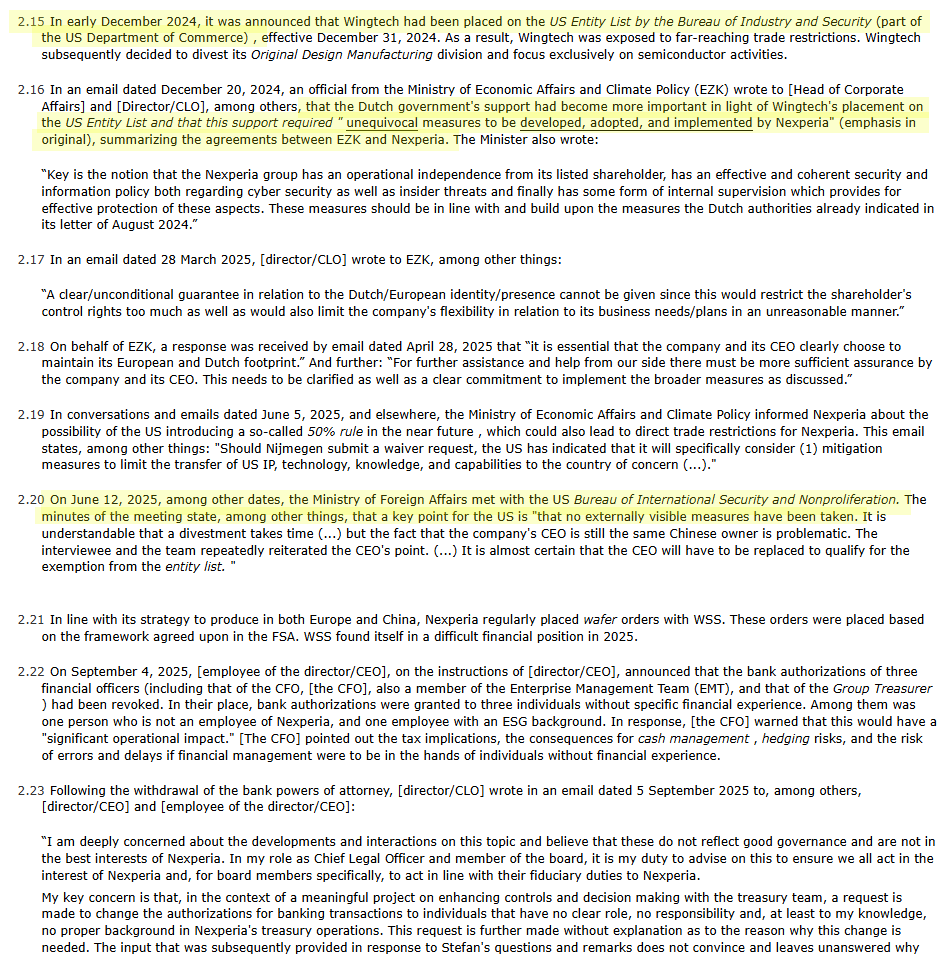

A detailed timeline of the events described in the legal brief clearly show that the entire series of events were instigated by the addition of Wingtech, which indirectly owned/controlled 100% of Nexperia, to the Entity List.

A detailed timeline of the events described in the legal brief clearly show that the entire series of events were instigated by the addition of Wingtech, which indirectly owned/controlled 100% of Nexperia, to the Entity List.

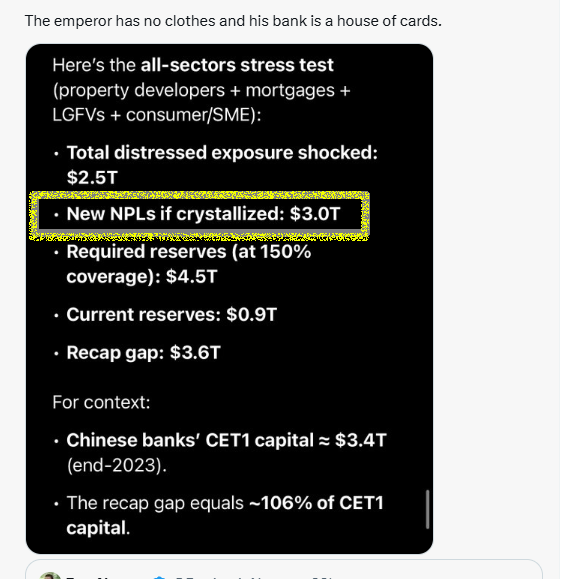

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/19780702951570968081⃣ Systemic risk from the property and LGFV sector have been contained

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1959701156235550929

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1657792283490545665

This number (which tends to range from 100 to 150) is actually derived from brands — ostensibly pulled out of the CAAM** database. Depending on how high the number is, it could include defunct, retired brands.

This number (which tends to range from 100 to 150) is actually derived from brands — ostensibly pulled out of the CAAM** database. Depending on how high the number is, it could include defunct, retired brands.

https://twitter.com/AndrewYNg/status/1971312147654377823Up to this point, China's semiconductor progress was halting, at best.

https://x.com/GlennLuk/status/1050758527617310722