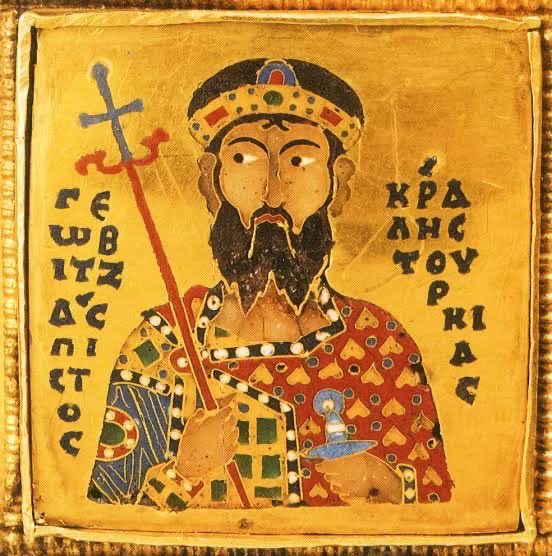

The Byzantine Empire before Manzikert was a superpower; but, this single battlefield defeat & infighting led to collapse.

Byzantium had been through worse & was known for stubborn resistance.

What changed & how is this a warning to governments tempted to take a similar path?

Byzantium had been through worse & was known for stubborn resistance.

What changed & how is this a warning to governments tempted to take a similar path?

Byzantine cultural & economic output during this period is huge; however, dynastic difficulties & corrupt imperial courts drained the treasury & enacted unsound policies. We’ll focus on the downstream effects of this which made the famously resilient Byzantine military so brittle

In the 1060s it’s clear, even with a lack of sources, that Doukid mismanagement had cost Byzantium much strength. But what about earlier? Historians seem split, especially regarding Constantine Monomachos.

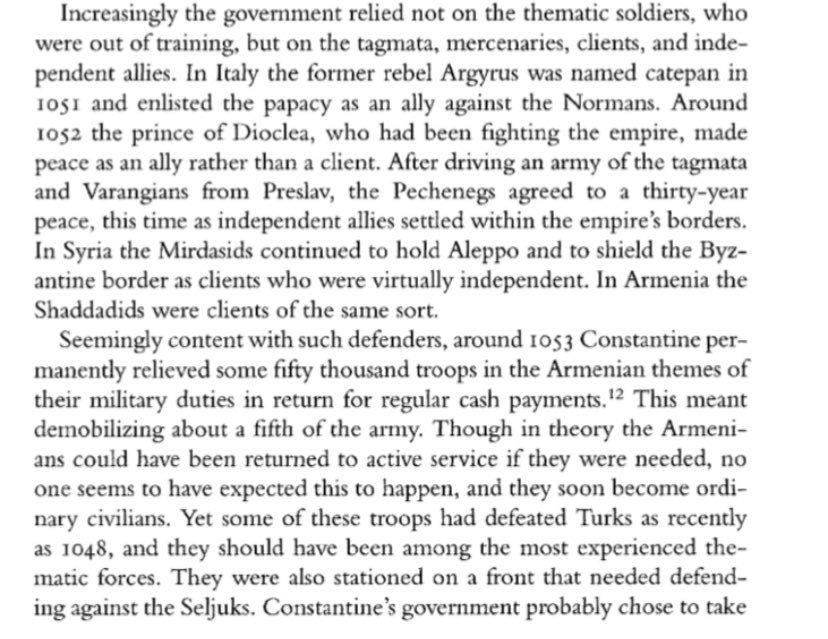

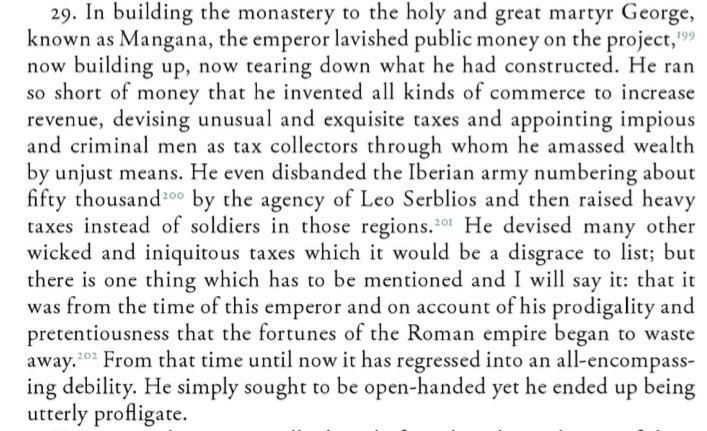

Warren Treadgold emphasizes Monomachos’s reliance on disloyal foreign “allies” militarily. This is drawn from Skylitzes who argues that this cost saving measure was used to budget for other priorities & personal projects.

Byzantine thematic units were disbanded in favor of foreign soldiery & professional troops, the quality of part-time soldiers is alleged to have declined so much as to make this necessary.

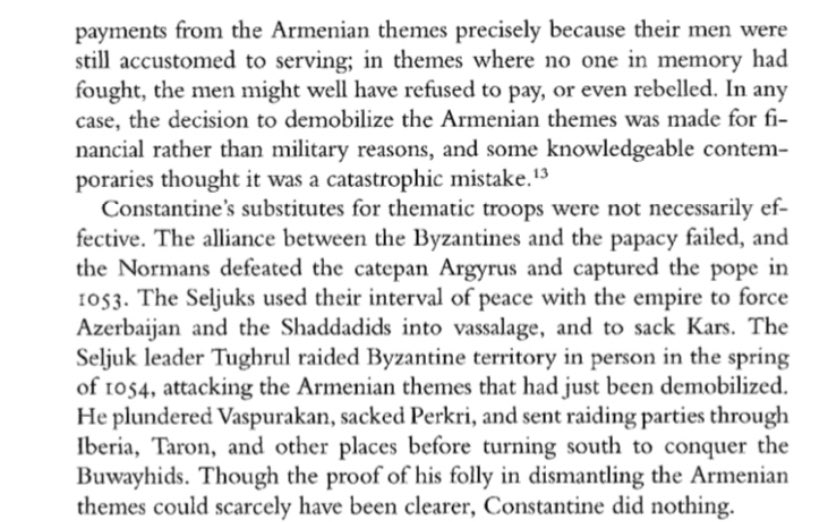

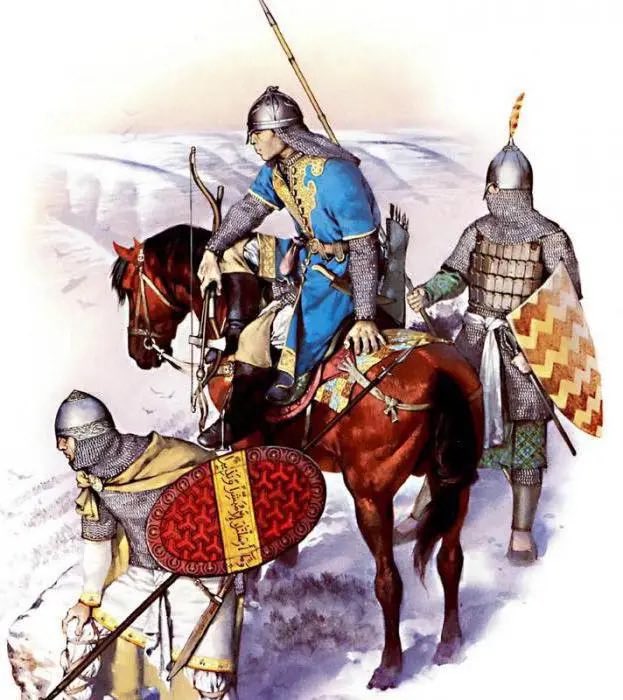

Skylitzes claims military obligations were fully transformed into taxes in Armenia leading to the discharge of an eye-watering 50,000 soldiers in the early 1050s. During this time Seljuk raids had begun to ravage the eastern borderlands, making this an unbelievable decision.

John Worley suggests similar policies were enacted in the Balkans. The Pechenegs were pacified & saddled with military burdens. This encouraged the disbanding of Byzantine formations as a cost-saving measure, leading to military revolts.

But is this really the case? Worley himself questions the scale, validity, & effect of these policies. Is hindsight projecting issues farther into the past than warranted? Kaldellis believes so & praises Monomachos for adequate management of serious & novel threats to the Empire.

Although Pecheneg & Seljuk attacks were serious issues for the Byzantines, Kaldellis argues they were met adequately & no major downgrade of the military can be inferred. Psellos hints that the military suffered from neglect under the Doukids.

It’s possible Skylitzes, writing during the reign of Alexios Komnenos didn’t wish to denigrate the family of his patrons & preferred to end his history before the Doukids take power, projecting the issues back onto the previous dynasty.

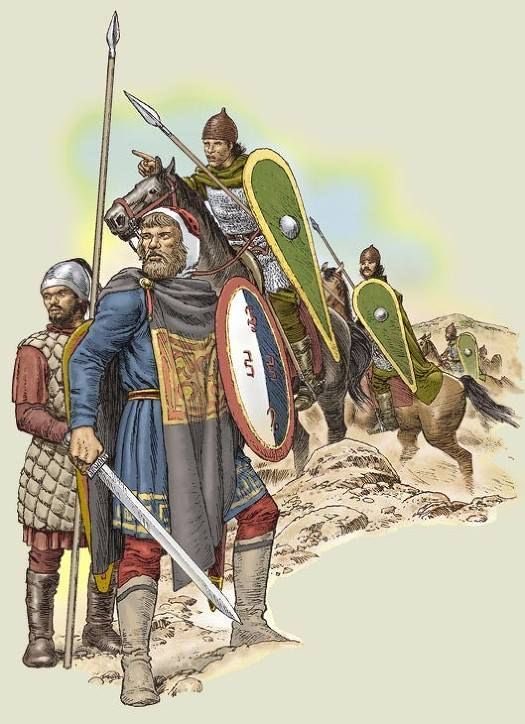

The transformation of the Byzantine military from a dispersed, part-time, defensive organization to a professional & often offensive standing army was a slow process from the days of Nikephoros Phokas until its culmination under Manuel Komnenos.

I believe this transformation made Byzantine resistance to invaders brittle. As Arab raids faded the thematic troops began to soften & seem unnecessary. Taxes were accepted rather than military service & funds used to pay for professional soldiers.

These changes began in the core areas of the Empire & slowly radiated toward the borderlands as threats receded. The professional replacements provided the force projection & military power of the Byzantine Reconquista begun by Nikephoros Phokas.

However, professionals are more expensive & in far more limited supply. Military defeats & budget cuts more rapidly degraded a professional Byzantine army than those of the old Theme system.

As new enemies appeared on the borders & the treasury drained after Basil II, the military began to slowly degrade. However, the Byzantine military remained an effective fighting machine, seeing off many enemies & winning battles.

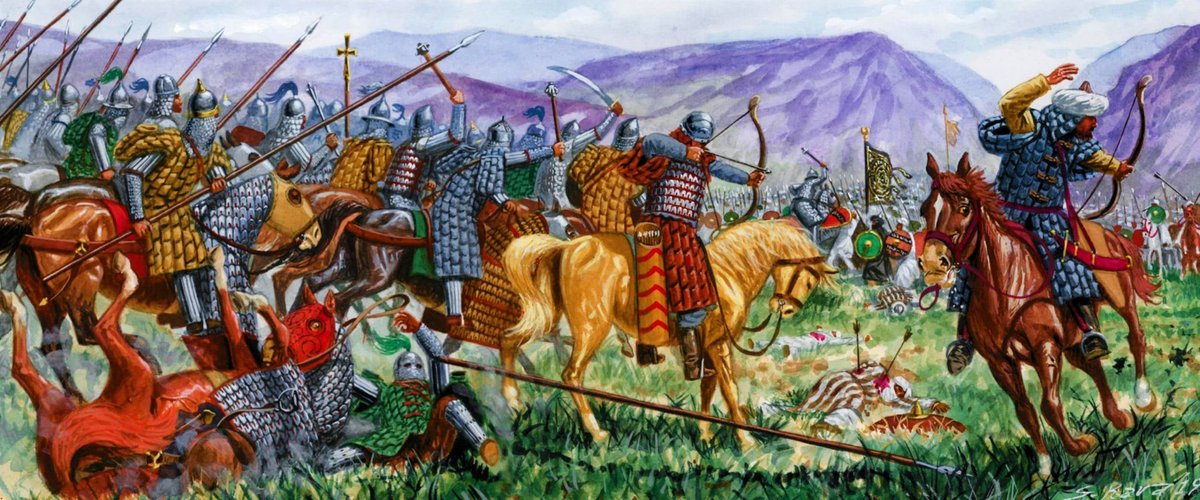

At closer examination much of this success is due to units of professional soldiers stationed on the frontier. When we hear of the successful repulsion of the Seljuks in 1054 and otherwise it is Varangian & Frankish units, not local militias, that are given the credit.

It’s possible Monomachos monetized the army obligations to be rid of ineffective soldiers. (did they refuse muster? Were they unreliable or unskilled in battle?) Whatever the case, Monomachos stationed enough professionals in these lands to see off threats.

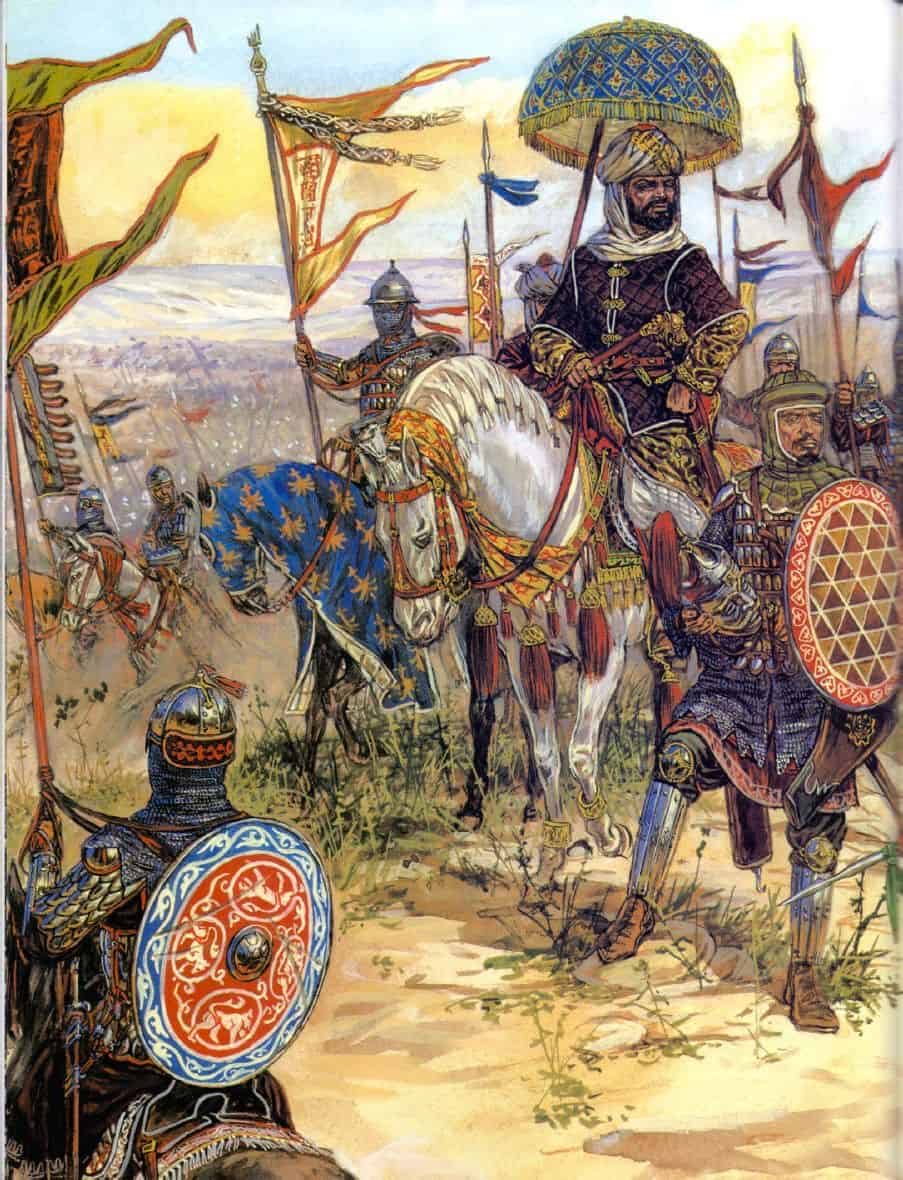

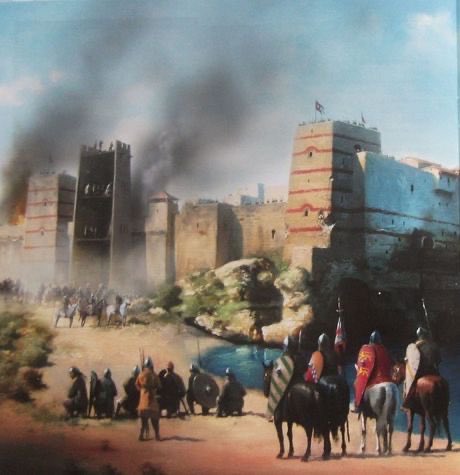

As the Doukids allowed the professional force to wither, problems mounted. Especially as their enemies were gaining strength. As the frontier units dissolved, Seljuk raids penetrated deeper & more destructively into Byzantine territory, sacking Ani in 1064 & Caesarea in 1067.

It’s clear that the Byzantine military remained capable & large enough for Romanos’s semi-successful campaigns up to Manzikert. However, Romanos was forced to scrape together all the men he could & race around the frontier, furiously trying to plug the gaps.

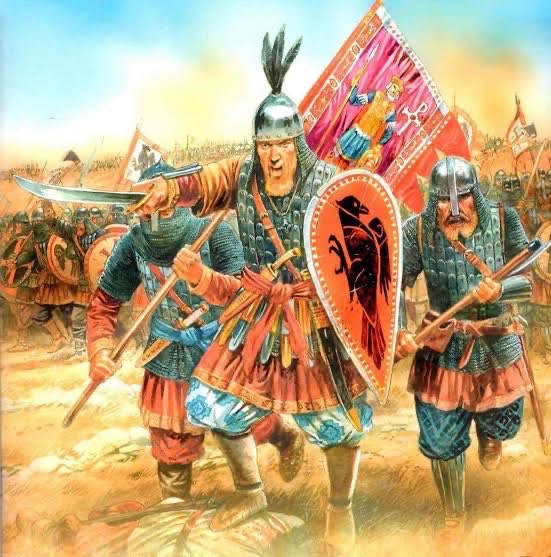

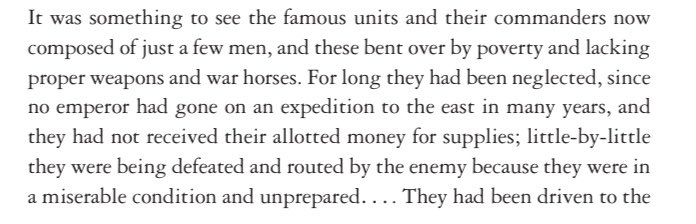

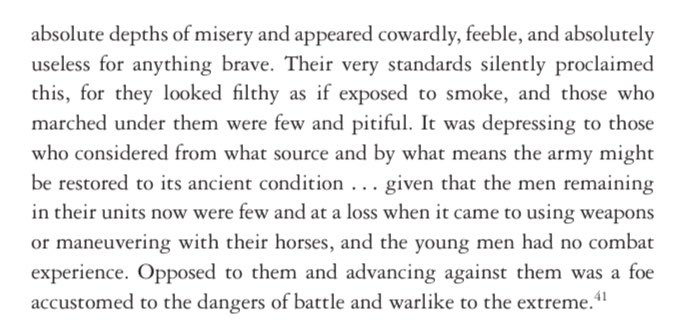

Psellos, with his typical flare for the dramatic, captured the desperate & neglected state of the once great Anatolikon Theme when Romanos called them to muster. Clearly the themes had withered & with many professionals dismissed by the Doukids, Romanos faced a real problem.

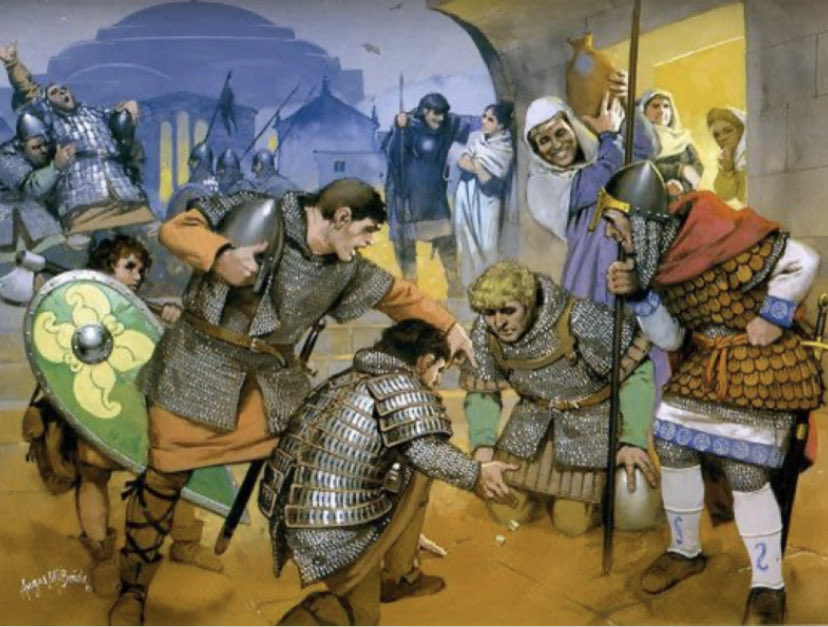

Sadly, the remaining professionals of Romanos’s army were shredded in the civil wars of the 1070s. The situation became so dire that the Byzantines relied heavily on foreign soldiers until late in Alexios Komnenos’s reign whether Normans, Turks, Varangians, Franks, or others.

Another key weakness from the transformation of military obligations to taxes was that a collapse in the professional military would mean capitulation of the civilian population.

Unaccustomed to self-defense, finding the invaders offered a lower tax burden, or cowed by their viciousness, local communities accepted foreign rule with little resistance, most notably during the Seljuk invasions of Anatolia.

There is no better military defense than a militia of freemen, guarding their communities. However, they are largely ineffective in offensive action, a professional army is more suited for this. The founding of the Tagmata, professional units, were in part a response to this.

The Byzantine military trade-off in the 10th century allowed for stunning conquests but also underlying vulnerability.

What do you think? Do you agree with Professor Treadgold or Professor Kaldellis? Are there any other examples of this phenomena you can think of?

What do you think? Do you agree with Professor Treadgold or Professor Kaldellis? Are there any other examples of this phenomena you can think of?

Enjoy the thread? Sign up for the Substack! New article will be published this week!

varangianchronicler.substack.com

varangianchronicler.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter