Prospect Theory's famous “S-shaped” value function is a cornerstone of behavioural economics. Surprisingly, more than 40 years after its inception, there seem to be a lot of remaining puzzles about it.

Or... perhaps not anymore. A 🧵that may change your view on Prospect Theory.

Or... perhaps not anymore. A 🧵that may change your view on Prospect Theory.

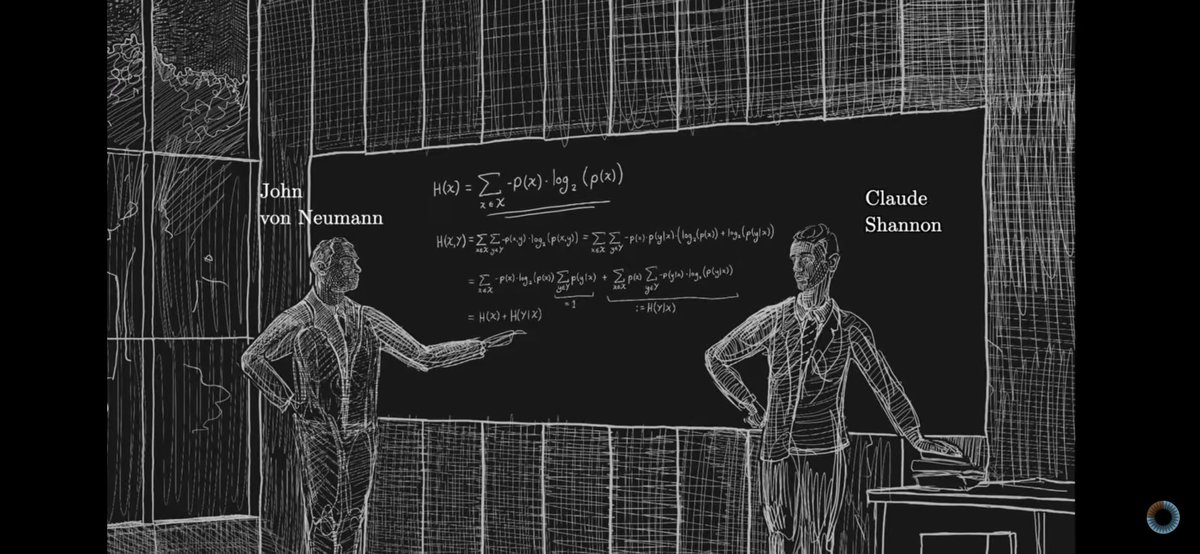

Since its publication in 1979, "Prospect Theory" by Kahneman and Tversky has become the most cited article in economics. One of its key ideas is that people value what they have by considering it as a gain or a loss relative to a subjective "reference point".

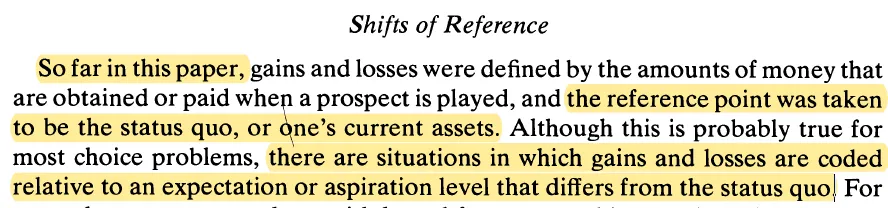

What is this reference point? Kahneman and Tversky did not propose a strict definition. It could be the status quo (what you have), expectations (what you think you'll get), or aspirations (what you would want to get).

https://t.co/55HZx44x8mjstor.org/stable/1914185

https://t.co/55HZx44x8mjstor.org/stable/1914185

Since then, “the question of what is the reference point has been a major topic in the literature” (O’Donoghue and Sprenger, 2018).

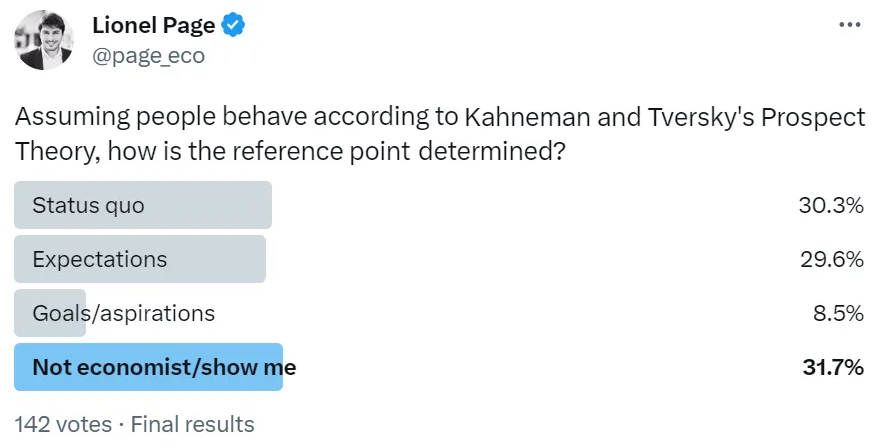

I asked economists on Twitter what they thought. Answers were split:

I asked economists on Twitter what they thought. Answers were split:

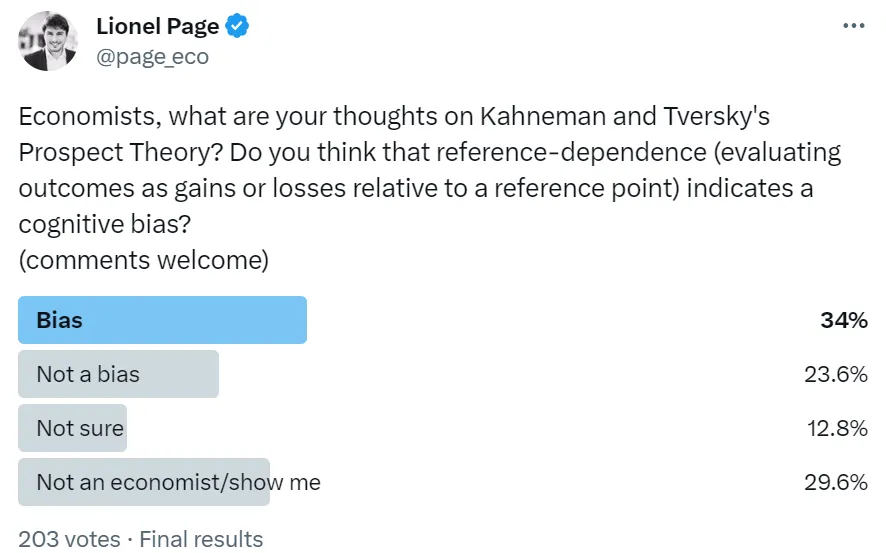

Another question is whether these "reference-dependent" preferences are a cognitive flaw. Kahneman and Tversky seemed to suggest so, pointing out that economic rationality is more in line with satisfaction being a function of absolute outcomes. Here again, I asked economists:

So what are the answers to these questions?

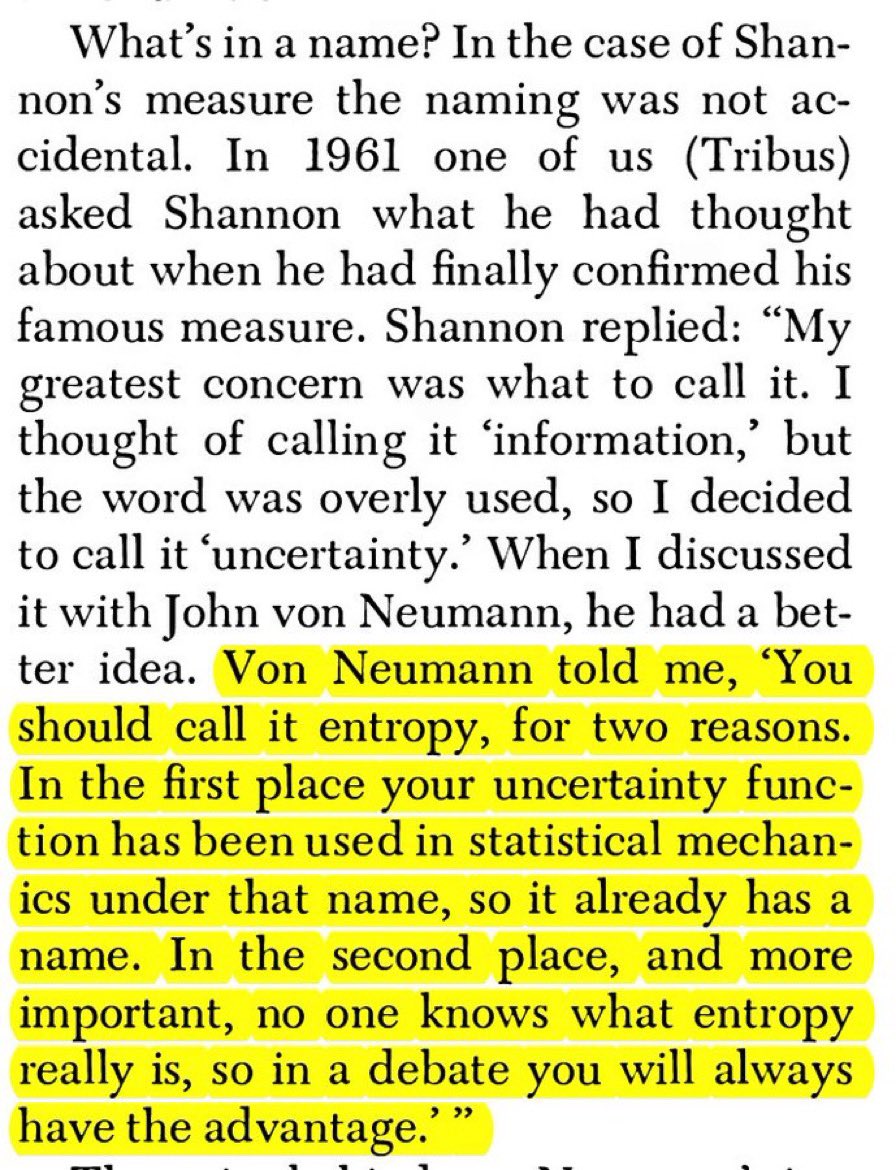

Unbeknownst to many people interested in behavioural economics, there is a simple and compelling theory that explains the origin and the features of the S-shaped value function.

Unbeknownst to many people interested in behavioural economics, there is a simple and compelling theory that explains the origin and the features of the S-shaped value function.

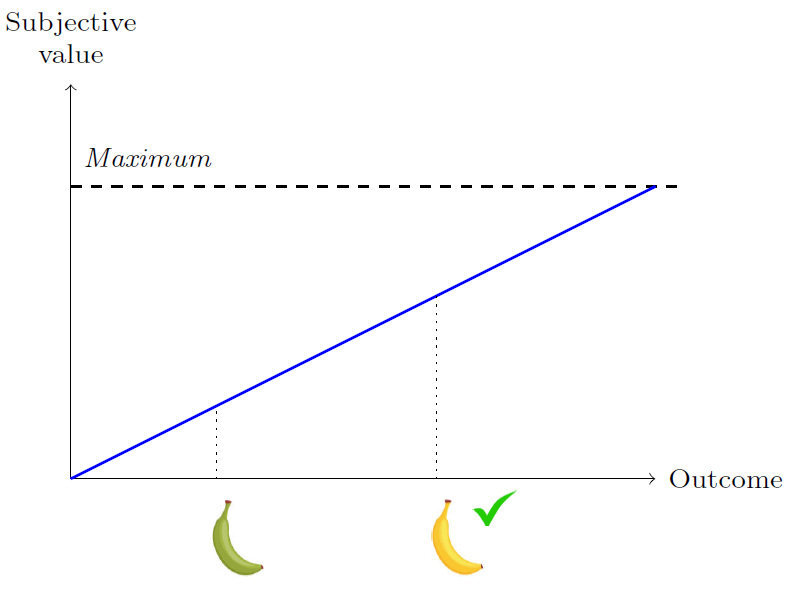

This theory can be explained simply. First, you have to consider what subjective satisfaction really is. A reasonable answer is that it is a way to encode the values of the options we face to guide our decisions toward good things and away from bad things.

Let's consider the choice between two options. Subjective satisfaction can be seen as an informative signal that helps us identify the best option.

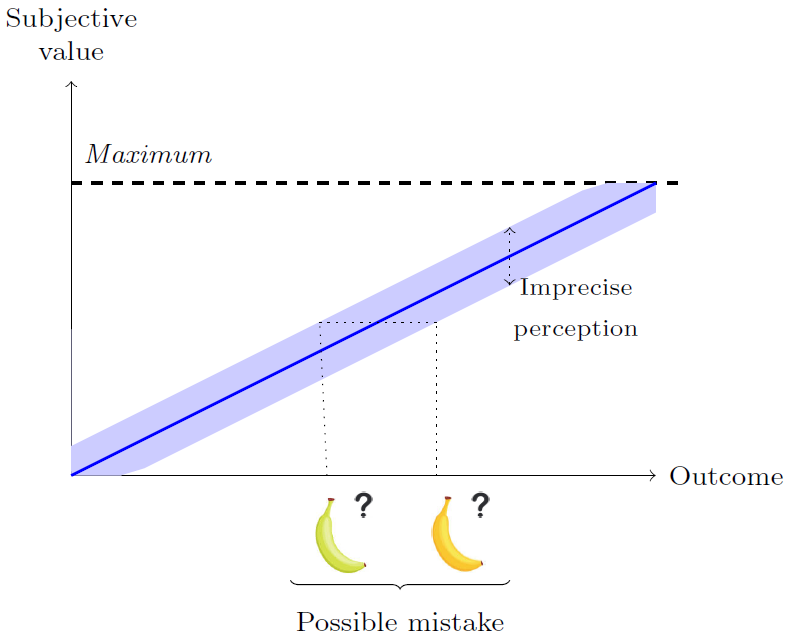

But our neuronal processes face biological constraints when generating signals of satisfaction. Let's consider two of them:

1) These signals must be bounded (limited number of neurons)

2) They can't be perfectly precise

Consequence: you can make mistakes when options are close.

1) These signals must be bounded (limited number of neurons)

2) They can't be perfectly precise

Consequence: you can make mistakes when options are close.

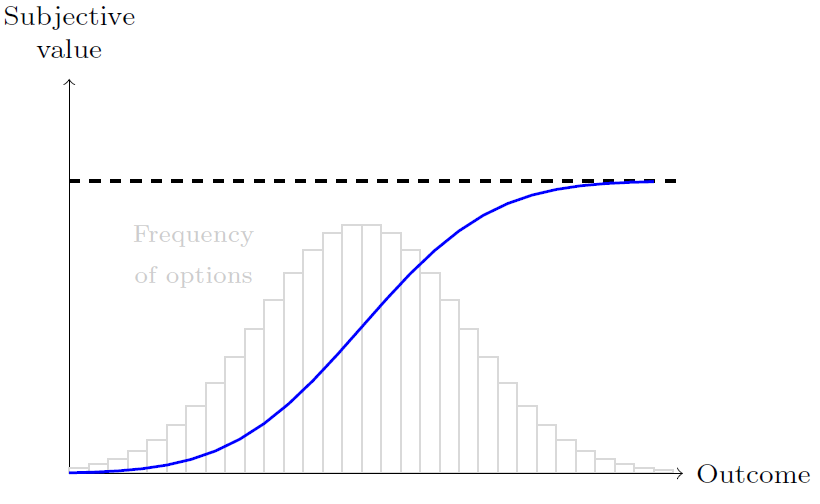

Can your system of perception be improved to reduce mistakes? Yes, it can be. When the slope of subjective satisfaction increases, it reduces mistakes between options that are close.

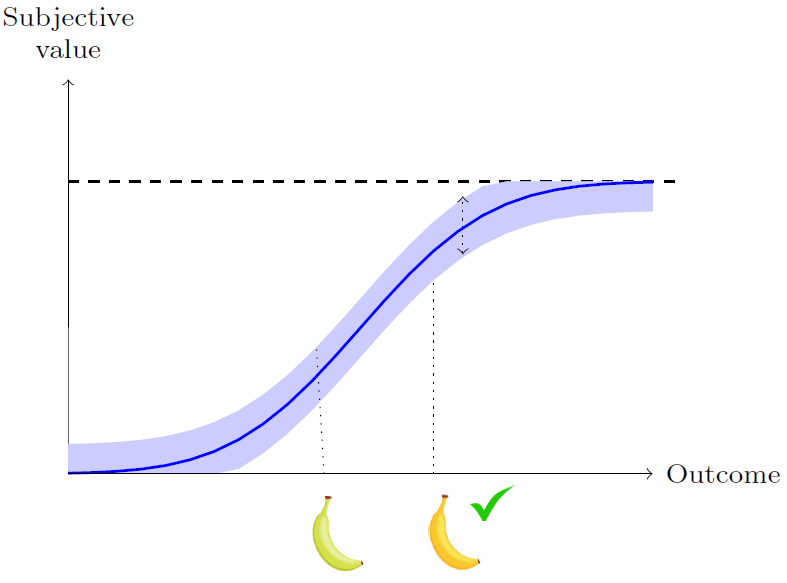

Since satisfaction is bounded, it can't be steep everywhere. The question is then: "Where should the slope of subjective satisfaction be steeper to limit mistakes?"

The optimal solution is that it should be steeper where you are more likely to face options to choose from!

The optimal solution is that it should be steeper where you are more likely to face options to choose from!

This formal result was established in complementary articles by Arthur Robson (Journal of Economic Literature, 2001), Luis Rayo and Gary Becker (Journal of Political Economy, 2007), and Nick Netzer (American Economic Review, 2009).

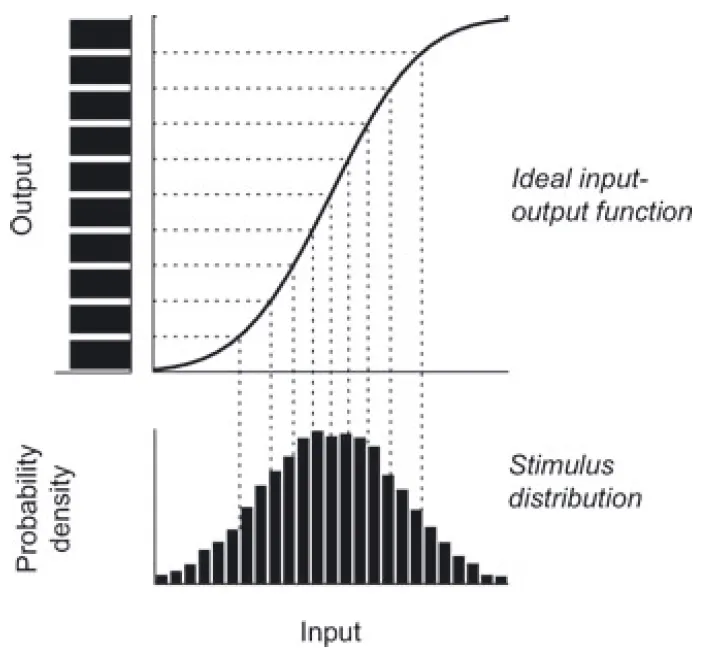

Beyond economics, this explanation is supported by results from neuroscience indicating that sensory systems respond to stimuli by following their distribution, an idea called "efficient coding". (Figure from Louie and Glimcher 2012)

This explanation solves many of the puzzles around "reference dependent preferences". First, these are not a flaw of human cognition. They are an optimal solution, under irreducible biological constraints faced by our perceptual systems.

Second, this explanation gives a straightforward answer to the question "what is the reference point?" If we identify the reference point as the centre of the S-shaped curve (assuming a symmetric distribution of options), then it is your *expectation*.

But expectations can vary. Often these are the status quo (you expect today the same as yesterday), and sometimes they differ from the status quo (like your expected higher income after you graduate from university).

Surprisingly, this simple and elegant explanation is currently largely unreferenced in behavioural economic texts. Even Dahmi's excellent and exhaustive "Foundations of Behavioural Economic Analysis" doesn't mention it in its 1799 (!) pages.

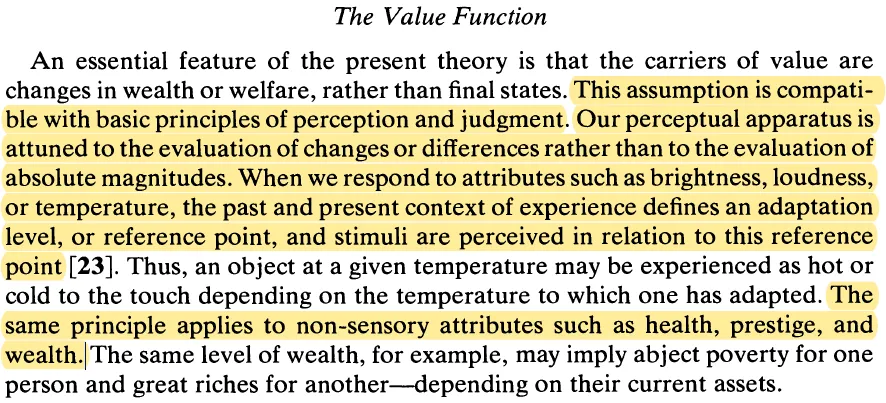

Noticeably, Kahneman and Tversky had seen the link with the features of perception in their 1979 paper. Behavioural economics simply did not explore this path extensively afterwards.

With the progressive integration of economics and neuroscience in the study of decision-making we are likely to see a growing interest in this explanation of reference-dependent preferences.

End/

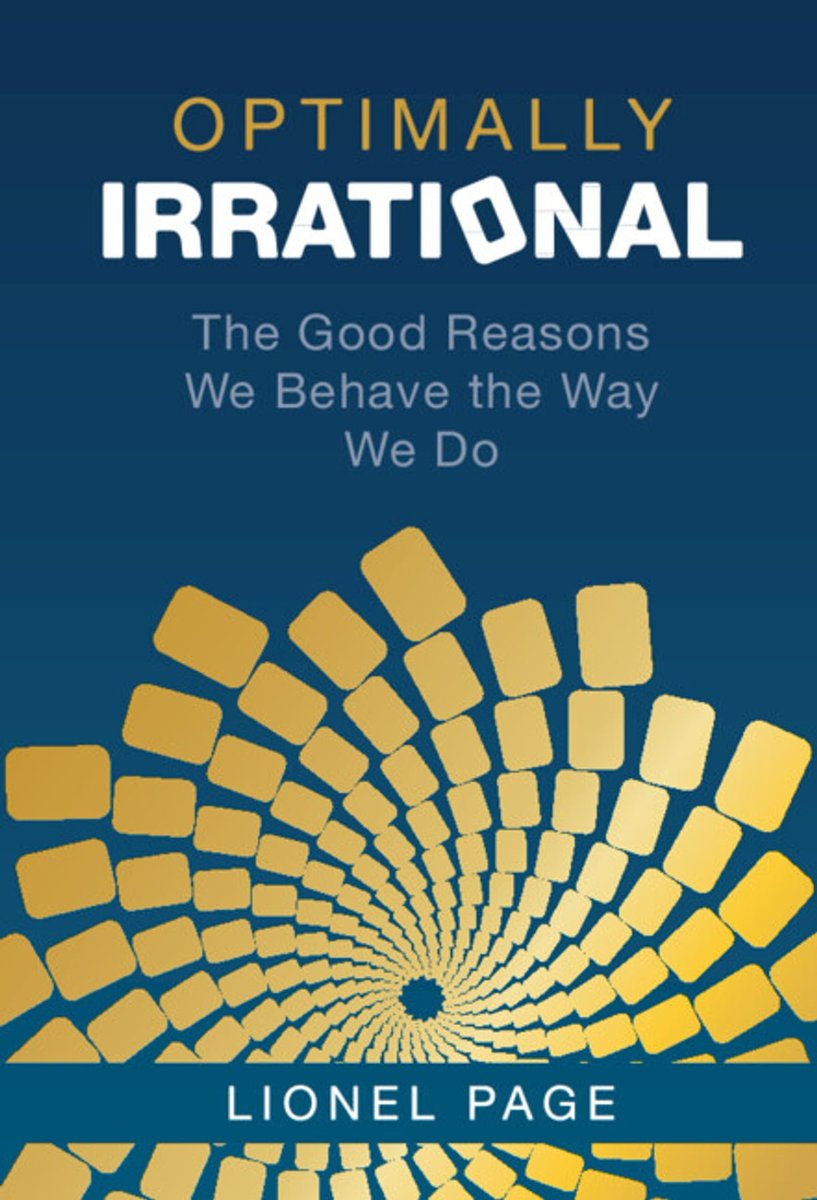

The ideas and references from this thread are included in this post which is the third of a series on widely known behavioural "biases". The next series of posts will be on game theory and how it unexpectedly explains a range of real-world phenomena.

https://t.co/kLsKKTFOwstinyurl.com/2wuu45wu

The ideas and references from this thread are included in this post which is the third of a series on widely known behavioural "biases". The next series of posts will be on game theory and how it unexpectedly explains a range of real-world phenomena.

https://t.co/kLsKKTFOwstinyurl.com/2wuu45wu

Final note: this thread did not mention "loss aversion". Indeed, loss aversion is... for another post.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter