The Byzantine Empire experienced both eddying heights & devastating catastrophes in the 11th century, what is the reason for this?

The inability to solve the security predicament of their geopolitical situation.

Was this rise & fall inevitable or could it have been prevented?

The inability to solve the security predicament of their geopolitical situation.

Was this rise & fall inevitable or could it have been prevented?

With the fading of Arab raids in the 10th century, the Byzantines conquered the Muslim Emirates near their borders. This was a strategic imperative to make the core of the empire safe & now possible with the breakdown of the Caliphate.

Early attempts were slow & produced mixed results until Nikephoros Phokas ramped up the professionalization of the military, making it more suited for offensive action. Results were immediate & Nikephoros swept aside all the remaining Emirates that had preyed on the Byzantines.

This offensive army grew in size & importance with the campaigns of John Tzimiskes & Basil II in wars of conquest, particularly in Armenia, Syria, & Bulgaria. These armies were eminently capable & doubled the size of the Empire, bringing the Byzantine Empire to its medieval peak.

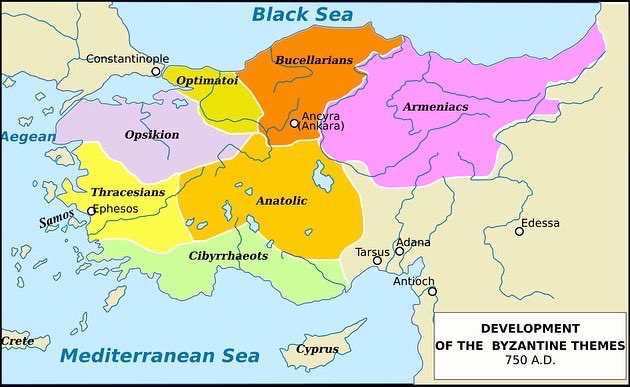

However, constant campaigning meant these soldiers needed to be full-time troops & without enemy incursions to necessitate militiamen, the themes decayed. Military obligations were transformed into taxes to maintain the professional army.

An earlier thread expounds on this transformation & its military/political consequences, go give it a read. Basically; militias are good at defense & professionals are better at offense, you don’t want one when you need the other.

https://twitter.com/varangian_tagma/status/1668619053404147712

Also, this professionalization was accompanied by centralization. Basil II, after facing two military revolts lead by the military elite of Cappadocia decided to break them. No longer would these military families be able to challenge the imperial government.

Basil promoted new men & families to military posts, ensuring their loyalty by preventing those with regional power bases from taking charge of the military as well.

The themesmen who once were paid through their governor & followed him into battle now paid tax to Constantinople or were paid professionals in the direct employ of Basil’s army. Local power was diffused & a threat to central power neutralized.

After Basil, the decadent imperial government drained the treasury & slowly degraded the professional army as a cost-saving measure. When strong foreign armies arrived at the borders they burst through the brittle remains of the professionals & found a docile populace.

There is much finger-pointing on the blame for this catastrophe, but was this the inevitable result of the professionalization needed to secure the borders in the 10th century?

All states fall, perhaps Byzantine decisions were mostly sound & hindsight is clouding our assessment.

All states fall, perhaps Byzantine decisions were mostly sound & hindsight is clouding our assessment.

Basil’s breaking of the Cappadocian Clique allowed the Constantinoplitan elite to rule without serious provincial revolts for decades. However, this robbed C. Anatolia of warlike men grounded in local communities that could repel invasions like they had for centuries.

Had Basil not suppressed them they may have remained a pool of military talent that could take the reigns of government during times of trouble & throw invaders back from Anatolia’s interior. However, they may have also caused frequent civil wars & loosened Constantinople’s grip.

It is also not a guarantee these men would have remained warlike. As raids subsided there would’ve been little combat for the men of Cappadocia. These men could have simply become a decadent elite, lording over serfs from their palaces, no better able to resist invasion.

In reality the landed elite created both the disastrous Doukids & the brilliant Komnenoi. It appears that the Byzantines were able to produce great men equal to the challenges of their day, but not always able to arrest decadence & corruption before disaster.

So what could have prevented collapse? Systematically, stronger ducates on the borders with intact militias & professional detachments. This would maintain a militarized elite & population in the borderlands, better able to fend off attacks.

This could be coupled with an annual campaign season for which men across the empire are conscripted, maintaining a healthy mix of professional & militiamen in the army & investing the citizens in the political & military success of the Empire.

However, this raises issues. The military elite of the ducates could still become an issue for the central government & ruling over foreign peoples might have established their own kingdoms or shattered centralized control.

Transforming the Empire into a monstrosity resembling the later HRE was unlikely to solve problems & rather encourage dissolution. However, the unique power of Constantinople relative to the provinces had always encouraged centralization, only when lost did Byzantium fracture.

It’s impossible to know for sure, but the lifecycle of Empire means that victory bears the seeds of defeat. It is clear however that state collapse need not mean the collapse of a nation.

The frivolity of imperial governance & demilitarization of Anatolians encouraged this latter phenomenon. Had local institutions remained stronger & more popular, Byzantine attempts to roll back Turkish invasions like those of the Arabs may have proved fruitful.

Had this occurred Anatolia may not have been transformed into the cradle of the modern Turkish nation. When Heraclius settled the armies into the provinces, establishing what would become the Theme System, he localized defense & saved Anatolia from the fate of Egypt & the Levant.

Had, say, Isaac Komnenos relocalized defense the Byzantines would have likely lost some peripheral conquests due to diminished offensive capacities & retreated to the natural barriers of the Haemus & Taurus Mountains. (Not unlike earlier abandonments of Dacia & Mesopotamia)

It’s possible Romanos could have snatched victory from the jaws of defeat by doing the same in the wake of Manzikert & empowered governors in Antioch, Cilicia, & Trebizond who rose up to take charge of local defense with mixed success. However, the Doukids had other plans.

Civil war shattered this possibility & the Komnenoi found many in the Anatolian interior unenthusiastic about a return to Byzantine rule, as well as personally cautious for fear of creating rivals through expansion.

What do you think?

What do you think?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh