One of the most important findings in the recent IPCC report is that we ultimately determine how much warming will occur.

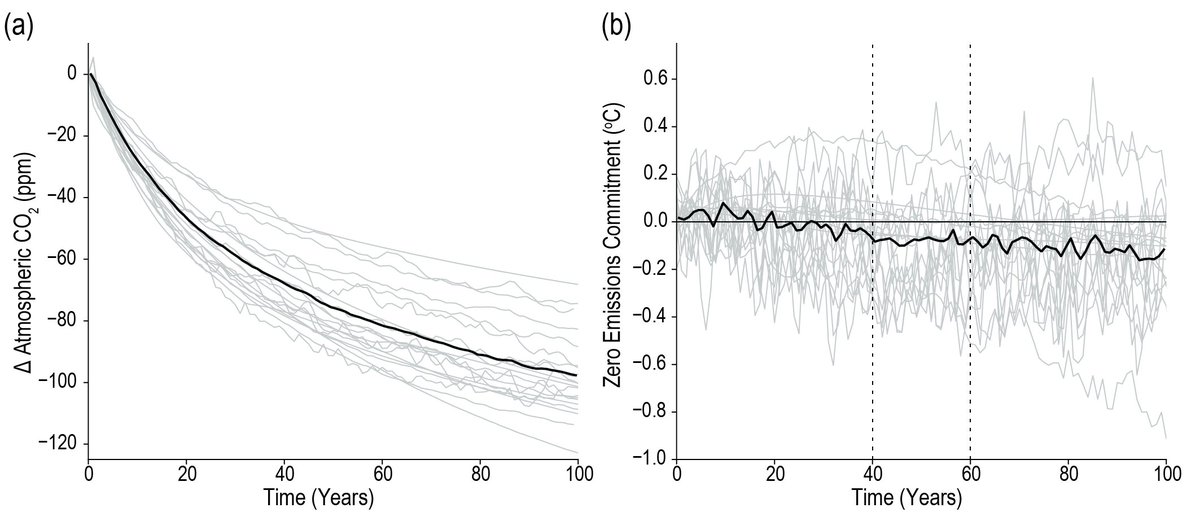

There is likely no warming "in the pipeline" once emissions get to zero. Rather, CO2 concentrations fall and temperatures stabilize https://t.co/SQl5waLZtRcarbonbrief.org/explainer-will…

There is likely no warming "in the pipeline" once emissions get to zero. Rather, CO2 concentrations fall and temperatures stabilize https://t.co/SQl5waLZtRcarbonbrief.org/explainer-will…

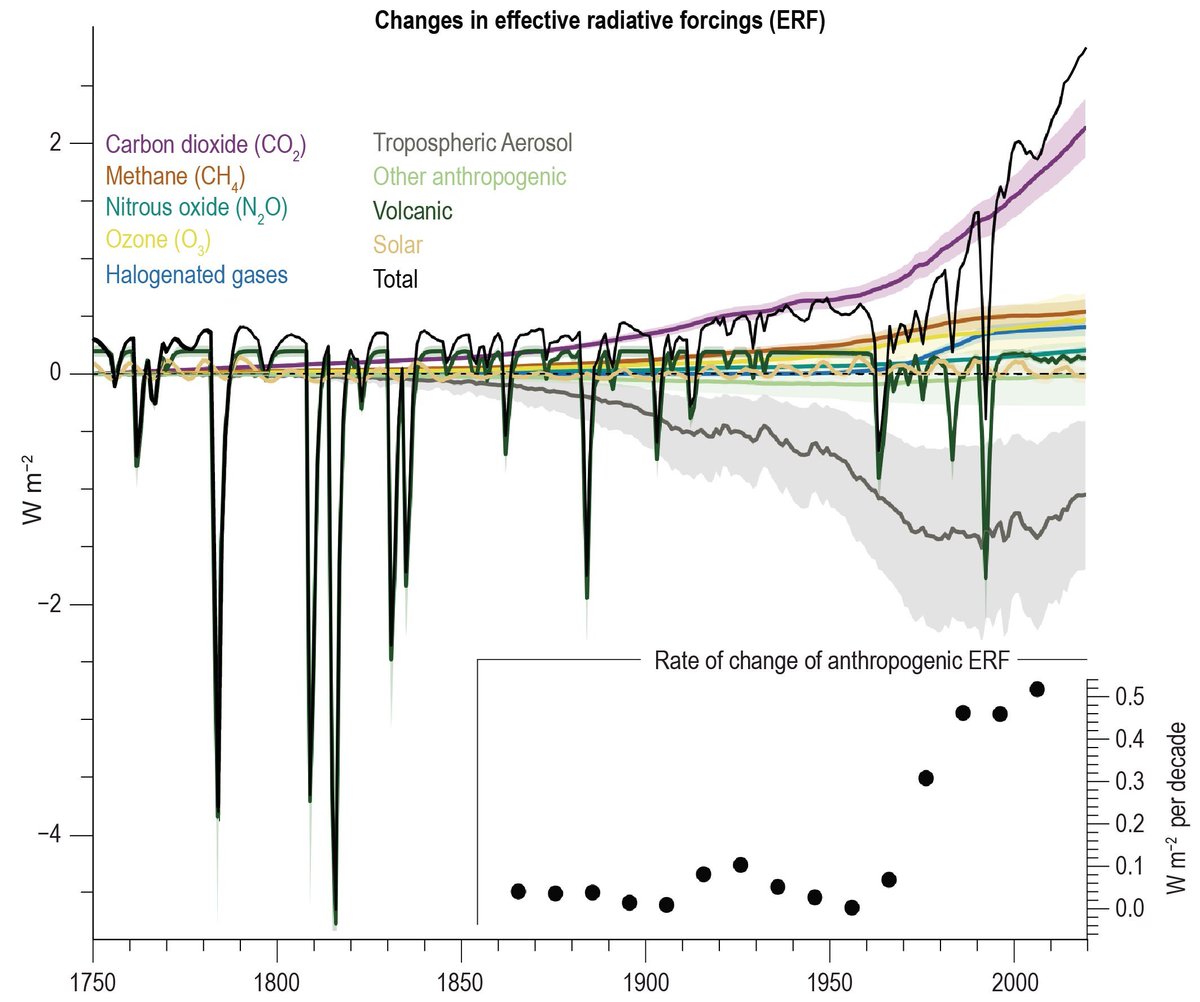

Why does this happen? As emissions fall, land and ocean carbon sinks start taking up more CO2 than we emit, as they work through a backlog of our past emissions. This causes atmospheric CO2 to fall and (all things being equal) would cause cooling. bg.copernicus.org/articles/17/29…

At the same time, the oceans are continuing to absorb heat trapped by greenhouse gases, and their slow warming reduces ocean heat uptake from the atmosphere and warms the surface. It turns out that these two factors largely cancel each other out over time:

Of course, there are some caveats. The zero emissions commitment has some uncertainty (+/- 0.3C) across models. Adding in non-CO2 GHGs complicates the picture. And most scenarios examined focus on limiting warming to ~2C at net zero; higher warming might trigger more feedbacks.

But the takeaway is this: the warming the world will experience this century depends on our emissions. Its not too late, large amounts of future warming are not inevitable, but if we don't start reducing emissions soon we will lock in dangerous warming for centuries to come.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter