Military ethics, for when soldiers are asked to do something legal under the Law of Armed Conflict but morally disastrous.

They don't really exist - they're certainly not codified and enforced properly in any force I know of - but they should.

Thread ⬇️

They don't really exist - they're certainly not codified and enforced properly in any force I know of - but they should.

Thread ⬇️

But Major Warlord, you say - the US military has ethical requirements!

Yes, it does. They're the same government-employee ethics any civilian bureaucrat has to adhere to. Don't accept lavish gifts, don't make your subordinates run errands, don't commute in government vehicles.

Yes, it does. They're the same government-employee ethics any civilian bureaucrat has to adhere to. Don't accept lavish gifts, don't make your subordinates run errands, don't commute in government vehicles.

I'm talking about actual professional ethics for soldiers, which I have been told ad nauseum is a real profession but which lacks a key characteristic of such - an ethical code dealing with the profession's actual duties.

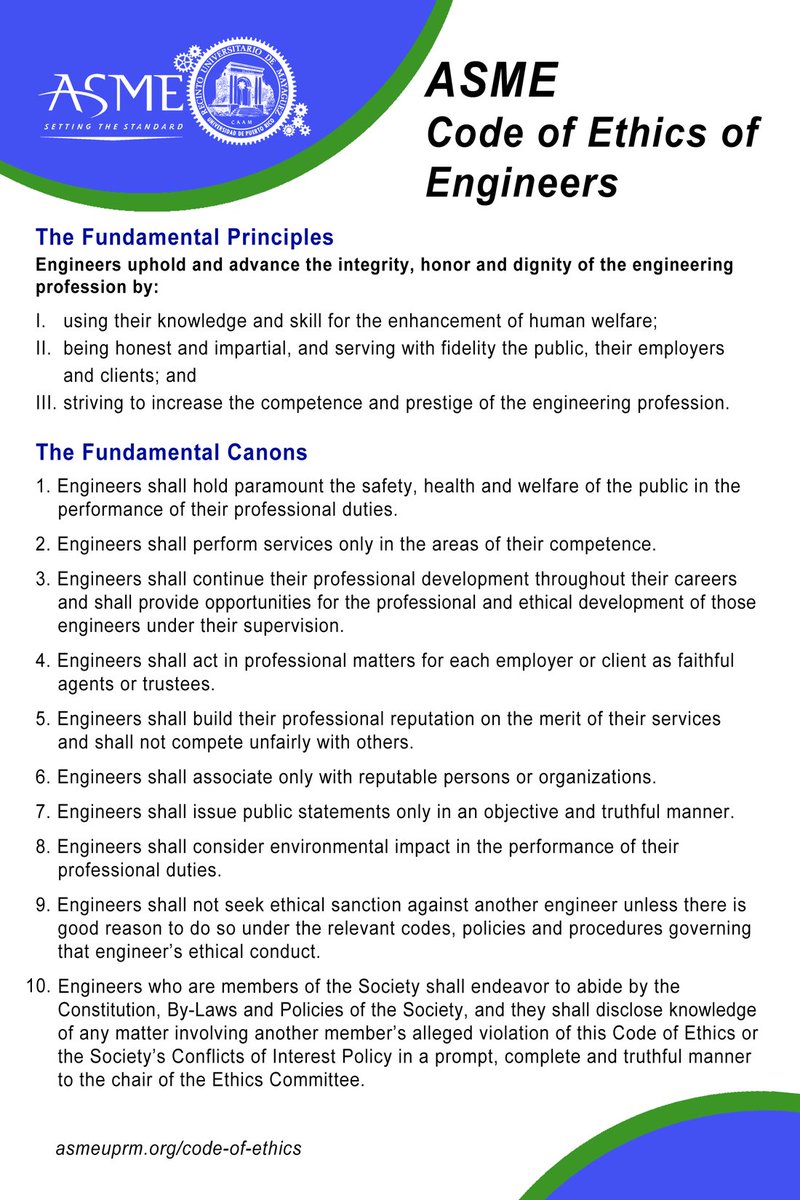

Lawyers, doctors and engineers all have ethical codes.

Lawyers, doctors and engineers all have ethical codes.

This is distinct from a soldier's legal responsibilities, as is the case with any profession. Military law and the law of armed conflict are well-developed fields.

However, it doesn't take much imagination to see that many things that are legal can be deeply unethical.

However, it doesn't take much imagination to see that many things that are legal can be deeply unethical.

The Geneva and Hague Conventions were designed to prevent savagery - not stupidity or venality. They are also focused on what is permissible to do to the enemy rather than how a military should be running its own business.

So allow me to propose three ethical rules to start.

So allow me to propose three ethical rules to start.

Rule 1. Do not fight pointlessly, whether in victory or defeat. You're getting people killed for no reason.

History is filled with last stands that were ordered out of pride (see the graphic), but I have an entirely different example in mind.

History is filled with last stands that were ordered out of pride (see the graphic), but I have an entirely different example in mind.

After the Armistice of Compiègne was signed in the early morning of November 11th, 1918, ending the First World War, it was set to come into effect at 1100 hours that day - approximately six hours later.

News of this was quickly communicated to the armies in the field.

News of this was quickly communicated to the armies in the field.

Most commanders told their men to stand down.

John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, ordered the offensive to continue until the clock struck eleven. There were some 3500 American casualties AFTER the armistice was signed.

Clearly this was unethical.

John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, ordered the offensive to continue until the clock struck eleven. There were some 3500 American casualties AFTER the armistice was signed.

Clearly this was unethical.

2. Do not fight a battle - or refrain from fighting one - for purely domestic political reasons.

This is the corollary of civilian control over the military - sometimes civilian politicians will abuse that authority and issue arbitrary orders that cost lives.

This is the corollary of civilian control over the military - sometimes civilian politicians will abuse that authority and issue arbitrary orders that cost lives.

The most salient example that springs to mind is the fact there were two Battles of Fallujah.

After four American PMCs were ambushed, tortured, and burned alive in the city of Fallujah in March 2004, the US Marines were sent in to secure the city and capture those responsible.

After four American PMCs were ambushed, tortured, and burned alive in the city of Fallujah in March 2004, the US Marines were sent in to secure the city and capture those responsible.

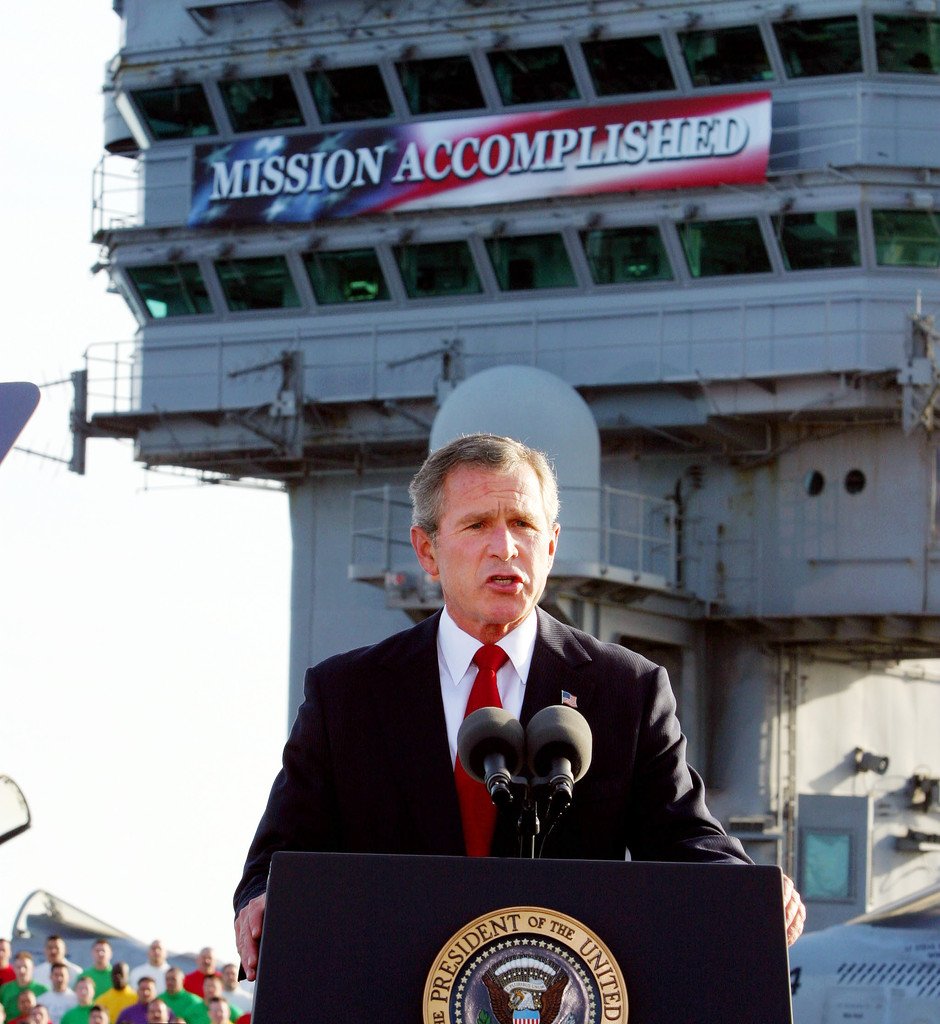

George W. Bush was, however, running for reelection then, and a key part of that reelection campaign was maintaining the illusion to voters at home that the Iraq War was over and the situation was under control.

A large battle with many American casualties would shatter it.

A large battle with many American casualties would shatter it.

So three weeks later, with American losses mounting, an order appears to have been issued from the top. Shut down the battle.

American commanders pulled back the Marines and sent in a local force, the "Fallujah Brigade," to "keep order." They of course defected immediately.

American commanders pulled back the Marines and sent in a local force, the "Fallujah Brigade," to "keep order." They of course defected immediately.

American troops simply cordoned off Fallujah and let the insurgents dig in for the next six months until - less than a week after Dubya won reelection that November - they went back in to do the job properly.

Dozens of Americans were killed and hundreds wounded in the fighting.

Dozens of Americans were killed and hundreds wounded in the fighting.

Clearly this was unethical - if the etremely suspcious timeline is anything to go by, George W. Bush was directing US forces in Iraq not based on any real military considerations but to bolster his reelection bid.

The generals went along with it.

The generals went along with it.

3. The lives of your allies should be as important to you as your own soldiers.

This can be seen in the rather blasé manner American commanders have treated casualties among "local" allies over the years. Let's look at the example of the Afghan National Security Forces.

This can be seen in the rather blasé manner American commanders have treated casualties among "local" allies over the years. Let's look at the example of the Afghan National Security Forces.

The Afghan government's security forces - the army and police - were not remotely trained, equipped, or led in such a manner as to remotely be comparable to NATO forces, despite the fact we had a generation to build capacity.

They were expected to compensate with their lives.

They were expected to compensate with their lives.

It was well known for years after the war was "Afghanized" with the withdrawal of most NATO forces that the Afghan forces that were supposed to have "stepped up" to maintain security were taking unsustainable casualties trying to do so.

(Taliban troops pictured)

(Taliban troops pictured)

For every Coalition soldier killed in action, twenty Afghan government soldiers died.

TWENTY.

And nobody advising this force - or even commenting on the matter - seems to have had the slightest concern for this beyond noting that attrition was an obstacle to force growth.

TWENTY.

And nobody advising this force - or even commenting on the matter - seems to have had the slightest concern for this beyond noting that attrition was an obstacle to force growth.

Clearly this was unethical, we were treating our local allies as expendable.

Of course not every partner force is going to be particularly capable, but the answer should never be to simply accept casualties, particularly among people who placed their faith and trust in the US.

Of course not every partner force is going to be particularly capable, but the answer should never be to simply accept casualties, particularly among people who placed their faith and trust in the US.

I could go on - a friend suggested looking past allied criminality, something that also corrupted the Afghan war effort. You do, however, get my point - none of this was illegal, but none of it should have been tolerated.

Hence the need for real military professional ethics.

Hence the need for real military professional ethics.

As a final note, I used high-level examples intentionally. I didn't want to tell stories out of my own personal experience dealing with much more banal versions of these dilemmas. Principles 1 and 3 can be readily adapted at any level, as can Principle 2 in some circumstances.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh