Did you know The Last Samurai is based on a true story?

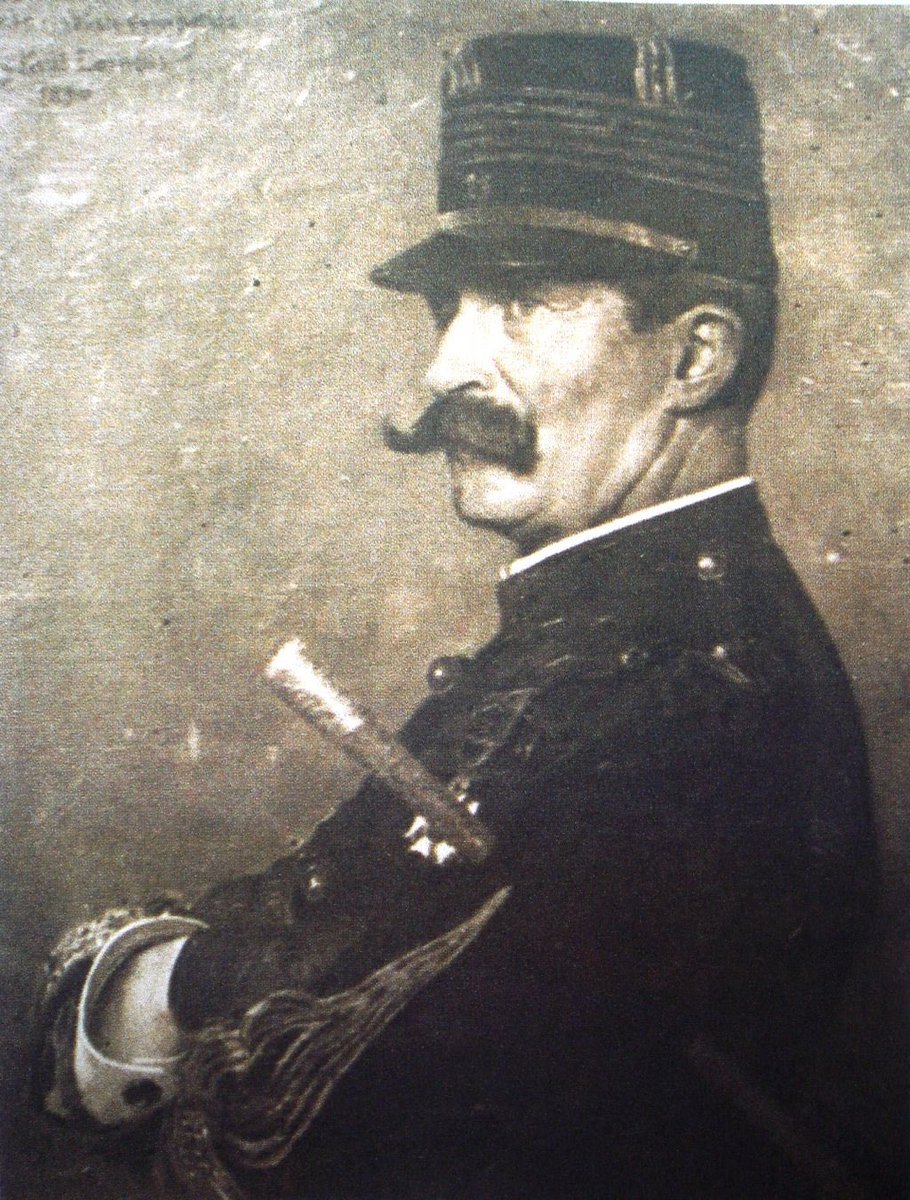

A thread on the incredible life & adventures of the real “Last Samurai;” Jules Brunet.

A thread on the incredible life & adventures of the real “Last Samurai;” Jules Brunet.

Jules Brunet was born in Alsace, France in 1838. His father was a veterinary doctor in the army. Jules followed in his father’s footsteps & joined the French Army in 1855, attending the prestigious Saint-Cyr & École Polytechnique.

Although a middling student, Jules excelled at his training as an artilleryman, graduating fourth in his class. Soon after graduating from his artillery course in 1861 he was sent to the war in Mexico. Jules served with distinction as a sub-Lieutenant in the mounted artillery.

Jules fought with valor at the Siege of Puebla & was recognized with the Cross of the Légion d’honneur. In 1866, France resolved to send advisors to the Shogun to modernize his army. Jules was an obvious choice as the artillery advisor with his impressive academic & combat record

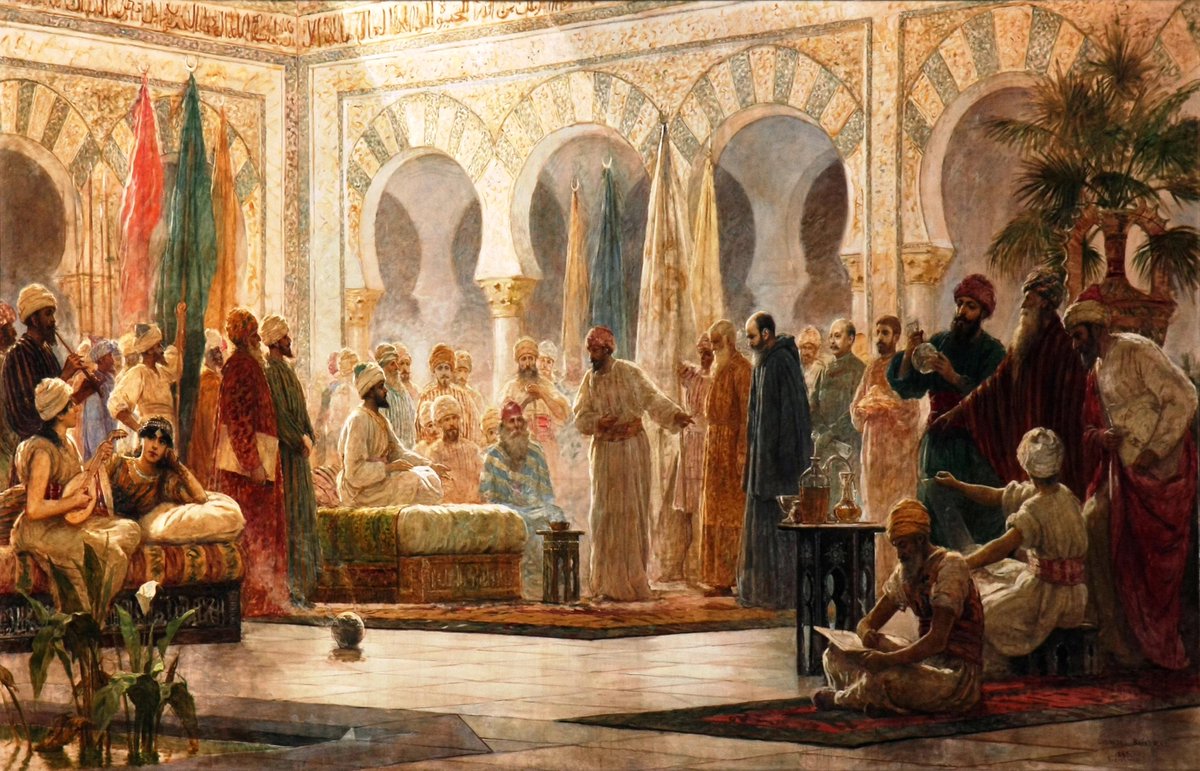

Jules expressed his “most great desire” to participate & at 28 was the mission’s youngest officer. Jules & the French Mission arrived in January 1867 & spent a year training the Japanese military. Japan only recently reopened to the world after centuries of self-imposed isolation

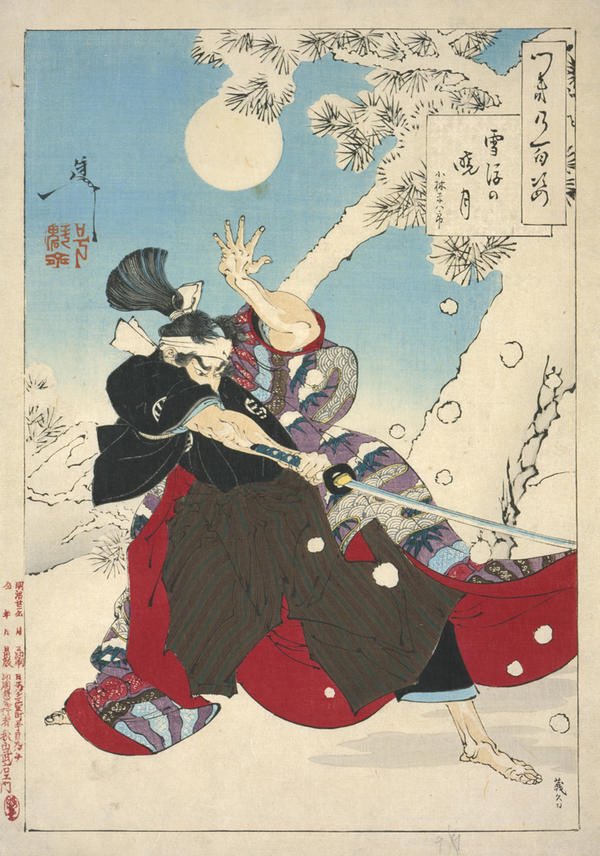

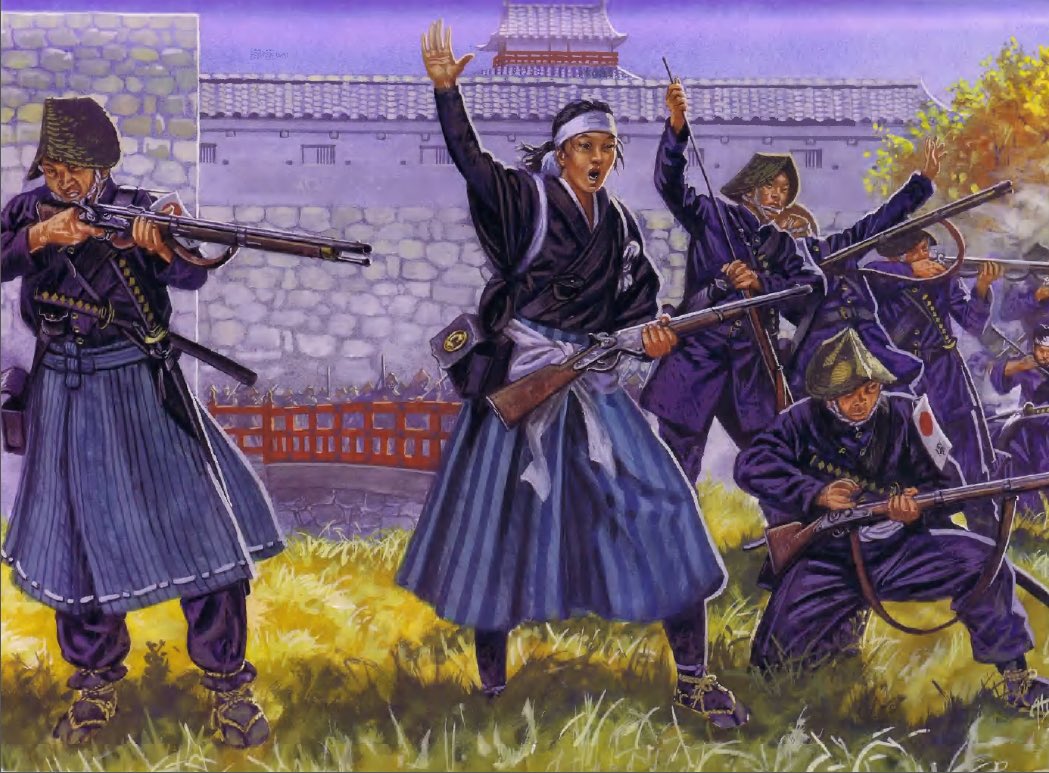

The army that welcomed Jules was still dominated by the Samurai. Although muskets now prevailed, the Shogunate’s equipment was seriously antiquated. Katanas were still ubiquitous & matchlocks, even pikes and bows, were not unheard of among the more traditional groups of warriors.

The French quickly began training an elite force for the Shogun. This was called the Denshūtai & was composed of 800 men in French-style uniforms & equipped with state-of-the-art equipment. This formation was intended to train & augment the Shogun’s less-modernized troops.

Western arms were flooding into Japan as clans & rivals jockeyed for power & Western governments vied for influence. Breech-loading artillery, modern rifles, & Gatling Guns soon made their way into the arsenals of Japanese warbands & the Imperial Army.

Jules’ knowledge of artillery gained the trust & confidence of the Shogun’s men. Jules himself became attached to the Samurai & their Bushido code. After a year with the Samurai, Jules felt bound to his new brothers in arms, especially as power struggles reached a fever pitch.

Japan’s forced entry into the modern world wasn’t easy. Many groups saw modernization as a way to grab more power, while others saw the changes as a threat to their way of life & political control. The struggle between the now-symbolic emperor & Shogun concentrated these forces.

Tension broke into open warfare in January 1868 when the 15 year old Emperor Meiji, supported by Choshu & Satsuma forces, declared his restoration to full power & resignation of the Shogun; Tokugawa Yoshinobi. Skirmishes broke out in & around Tokyo.

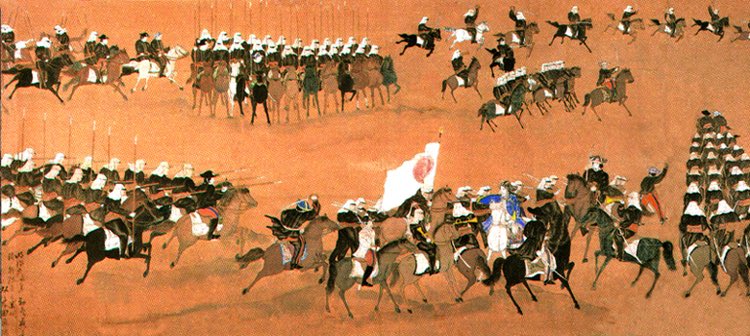

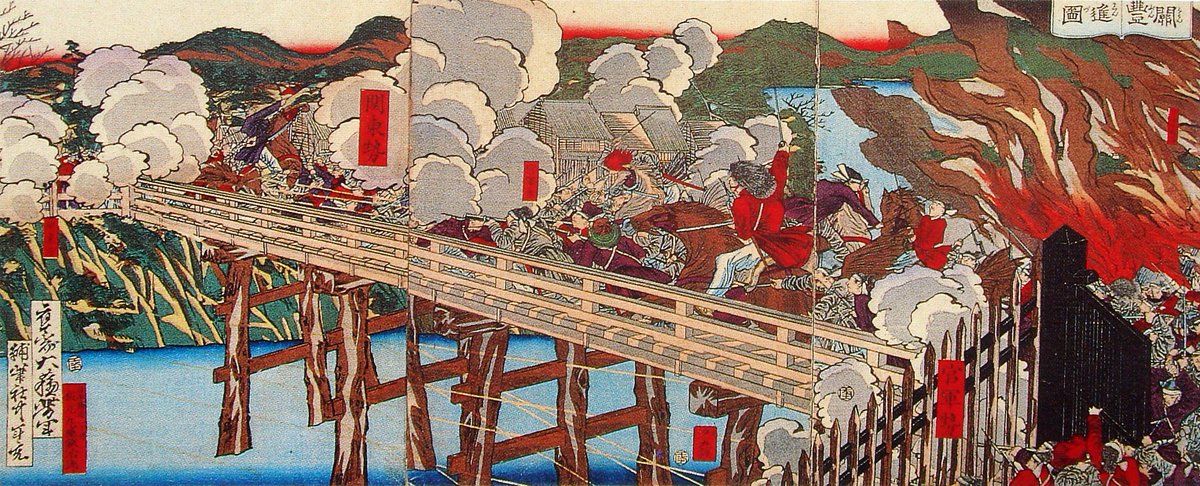

Jules marched with the Shogun’s army to Kyoto, where they planned to protest the Shogun & his supporters’ fall from power. They were met near Toba & Fushimi by the forces of Choshu & Satsuma. The Shogun’s 15,000 men outnumbered the opposing forces 3:1.

However, the Choshu & Satsuma forces had modern weapons; many of the Shogun’s men still used muskets & even the traditional katanas & pikes of the Samurai. As the battle progressed, the Shogun’s forces were devastated by the accurate rifle & artillery fire of the imperials.

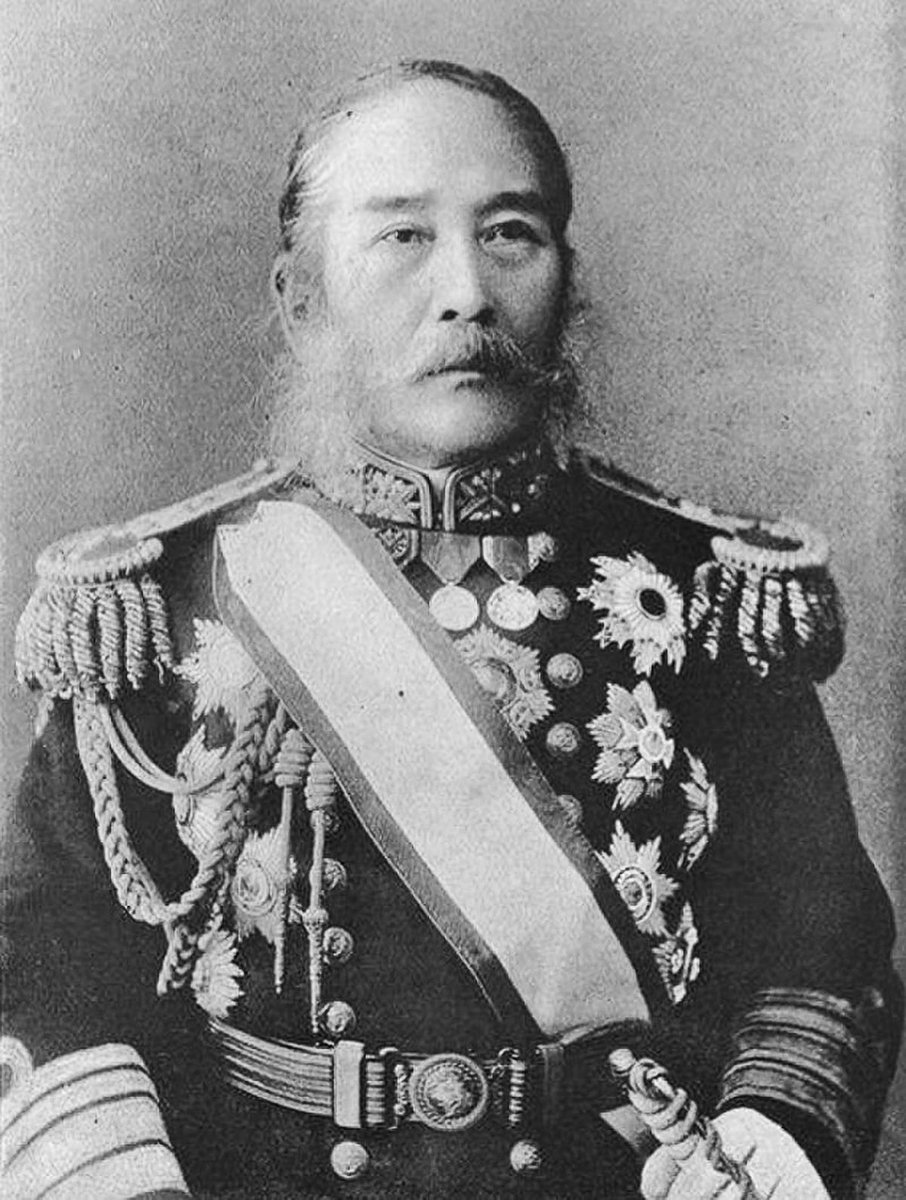

Defections also hampered the Shogun’s forces, and although casualties were fairly light, the Shogun’s retreat convinced many to throw in their lot with the Emperor. Jules & the men he trained were present at the battle & he followed the Shogun’s admiral, Enomoto, to Tokyo.

The Imperial forces surrounded Tokyo & crushed the forces of the Shogun, who surrendered & retired in disgrace. The Emperor ordered the French military advisors to leave the country, due to their role in training the Shogun’s men. Jules refused & resigned from the French military

Knowing his actions would be deemed treasonous or insane he wrote to Emperor Napoleon III, “A revolution is forcing the Military Mission to return...The Daimyos of the North have offered me to be its soul. I have accepted… I can direct the 50,000 men of the confederation.”

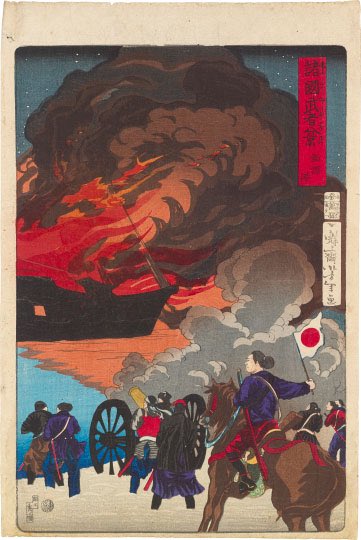

Jules went to Sendai where their forces were regrouping. The army here was more numerous than their imperial foes but woefully under-equipped. The fighting was fierce & the Shogunate fought desperately; building wood & rope cannons to fire stone projectiles.

In the end, the mechanical efficiency of modern weaponry proved too strong & Sendai fell.

Jules, ever-faithful, went with the shattered remnants of the army to Hokkaido. Led by Enomoto, the Shogunate forces formed a government, the Republic of Ezo, on the island.

Jules, ever-faithful, went with the shattered remnants of the army to Hokkaido. Led by Enomoto, the Shogunate forces formed a government, the Republic of Ezo, on the island.

Ezo was based off the American model & Japan’s only republic in its storied history. Jules took the role of its Foreign Minister & second-in-command of its army. Jules made contact with foreign governments, seeking recognition & aid. Ezo’s army had been divided into four brigades

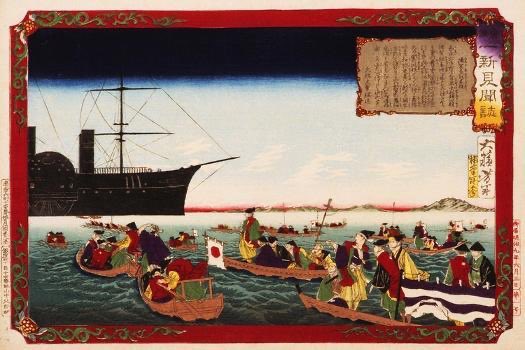

Each were commanded by a Frenchman. Two others, Collache & Nichol, were in charge of fortifying southern Hokkaido & the Navy. By Spring 1869, Imperial naval forces had defeated the Ezo’s depleted navy and landed 7,000 soldiers on Hokkaido to oppose Ezo’s 3,000 men.

Over the course of several months the Imperials ground down Ezo’s defenses around Hakodate. Just before Enomoto offered his surrender, the French soldiers escaped the Imperial besiegers and boarded a French naval vessel in Hakodate Bay.

Ezo had lost close to half their men & most of their ships by the time they had surrendered on June 27th. The Japanese government demanded Jules & his comrades be punished; however, his actions had gained widespread approval in France & the request was denied.

Jules rejoined the French Army with a slight reduction in rank after a six month suspension. Jules went on to serve during the Franco-Prussian War with distinction & rose through the ranks of the French army in the following decades.

Jules’ friend, Enomoto later became the Minister of the Imperial Navy & through his influence Jules was rehabilitated in Japan & showered with awards.

Jules’ career of high adventure, bravery, & boldness are hardly captured by the Last Samurai. To see a Frenchman in his bright uniform commanding a battery of Samurai with their rope & wood cannons is a sight that goes to show history is stranger, more fascinating, than fiction.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter