Only one country comes close to disrupting U.S. hegemony in global popular culture:

Japan.

But why them?

Because popular culture isn't a subjective art form but an industrial export Japan's military funded for WWII propaganda to defeat Disney.

A 🧵 on industrial pop culture:

Japan.

But why them?

Because popular culture isn't a subjective art form but an industrial export Japan's military funded for WWII propaganda to defeat Disney.

A 🧵 on industrial pop culture:

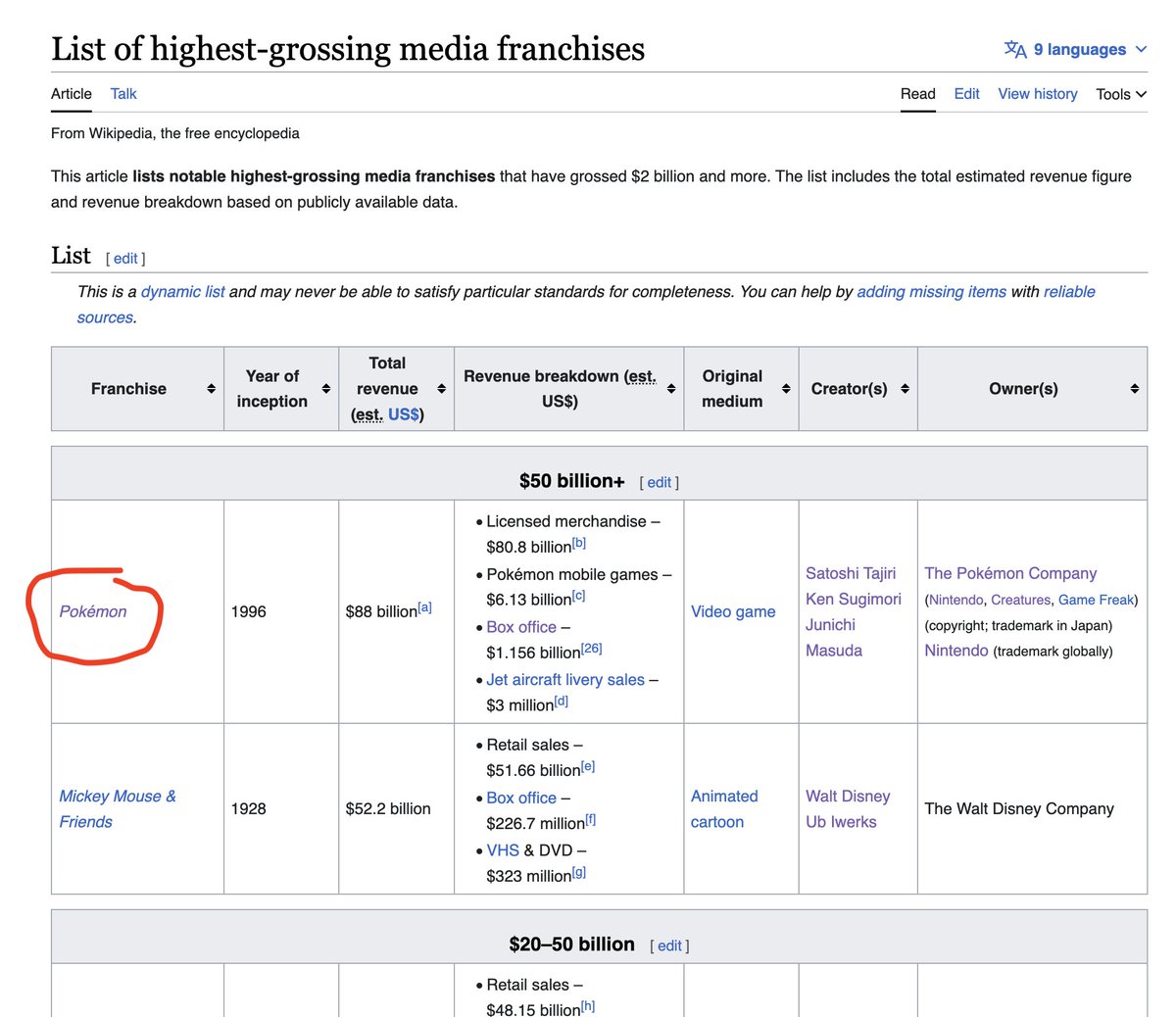

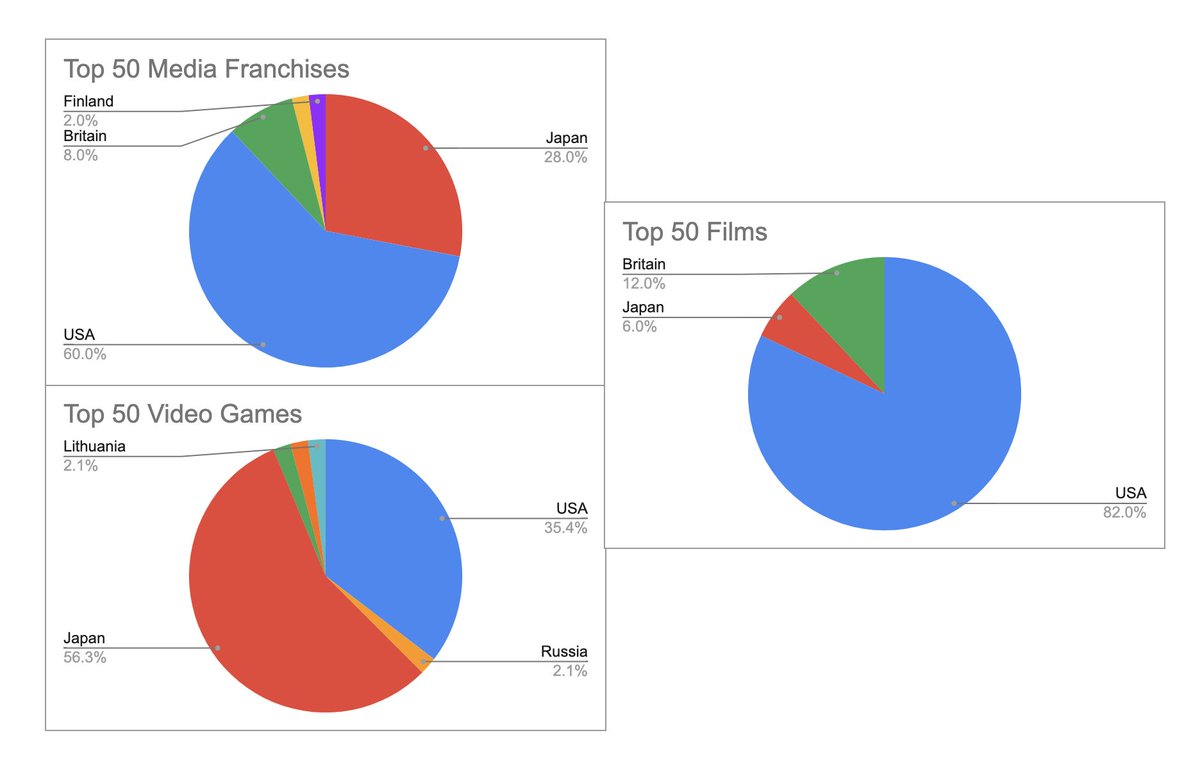

First, the evidence. Of the 50 highest-grossing films ever, 94% are based on U.S./UK intellectual property (IP).

The other 6% are Japanese. No other countries.

Japan is also 56% of the top 50 video games and 28% of the top media franchises, including number one: Pokémon.

The other 6% are Japanese. No other countries.

Japan is also 56% of the top 50 video games and 28% of the top media franchises, including number one: Pokémon.

Why, in fact, is all pop culture from English-speaking countries? Where is Europe? China? Brazil?

Music and books are also almost all U.S. or UK.

Our data sources are definitely hopelessly biased towards the U.S. Yet, even then, Japan alone somehow takes a slice of the pie.

Music and books are also almost all U.S. or UK.

Our data sources are definitely hopelessly biased towards the U.S. Yet, even then, Japan alone somehow takes a slice of the pie.

No theory of population/GDP can explain this.

China and India fail despite population. Germany is non-existent in culture despite its economy. France or Italy have high culture, but nothing in pop culture.

Singapore, Qatar—the richest states are also all cultural wastelands.

China and India fail despite population. Germany is non-existent in culture despite its economy. France or Italy have high culture, but nothing in pop culture.

Singapore, Qatar—the richest states are also all cultural wastelands.

At this point, most default to aesthetic explanations: “Japan just makes uniquely better games/animation. It’s magic oriental spiritism that speaks to the soul.”

We like to believe cultural products win on their intangible aesthetic merits. But history tells a different story.

We like to believe cultural products win on their intangible aesthetic merits. But history tells a different story.

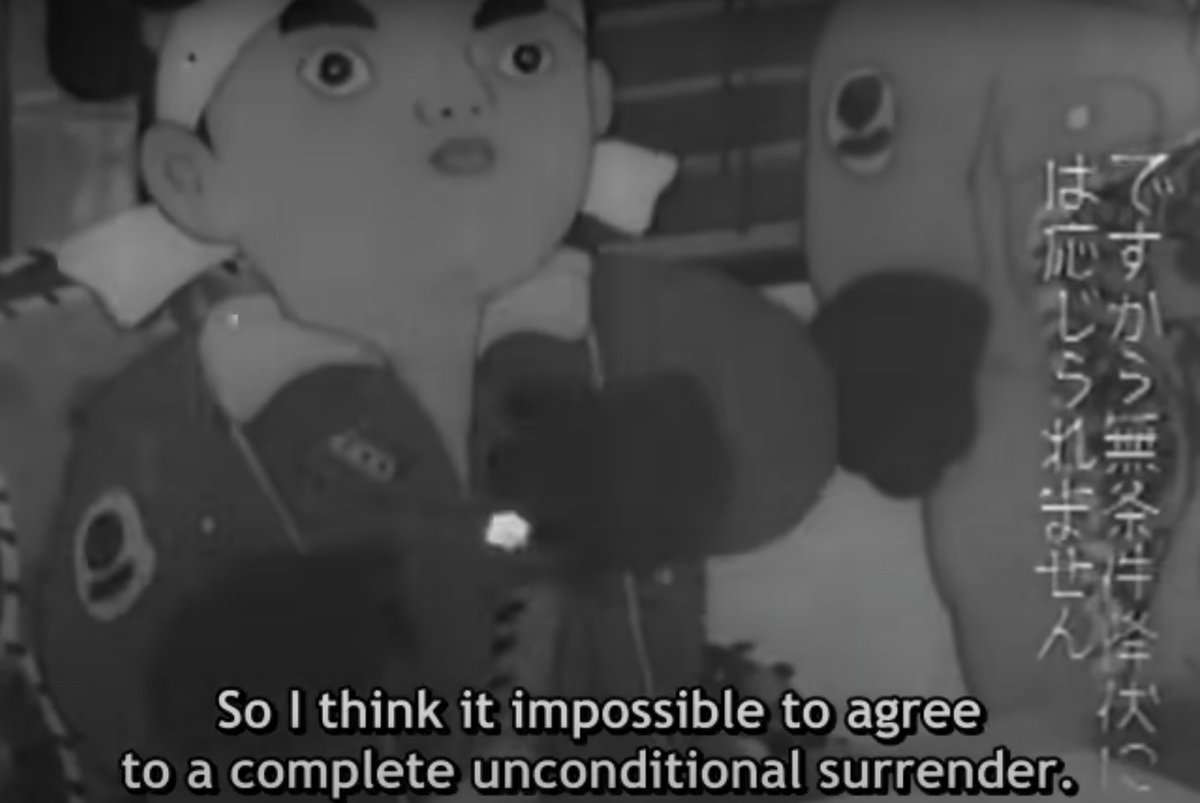

The first feature-length Japanese animated film is Momotaro: Sacred Sailors, released in 1945.

Not after the war ended—before!

It’s about how a cute little Japanese boy and his cute puppy and monkey friends complete naval air training then invade Indonesia to oust the British.

Not after the war ended—before!

It’s about how a cute little Japanese boy and his cute puppy and monkey friends complete naval air training then invade Indonesia to oust the British.

A prequel to this film, released in 1943, is about the same army of cute Japanese animals bombing Pearl Harbor.

This Momotaro 1 was literally the most-viewed film in Japan in 1943. It was an unprecedented box office hit. https://t.co/k8zSZYzmf8

This Momotaro 1 was literally the most-viewed film in Japan in 1943. It was an unprecedented box office hit. https://t.co/k8zSZYzmf8

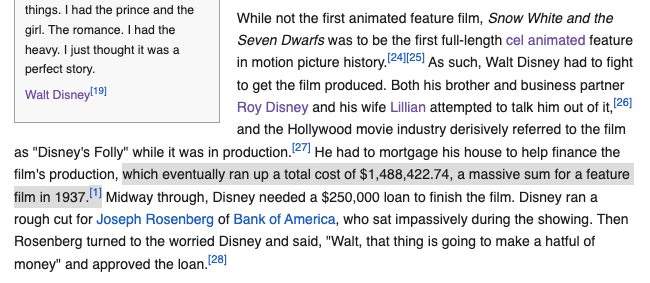

This was huge back then. The first-EVER animated feature film was Walt Disney’s Snow White, only released in 1937.

It blew audiences away worldwide with its quality animation and instantly became the highest-grossing sound film: brief.bismarckanalysis.com/p/disneys-boar…

It blew audiences away worldwide with its quality animation and instantly became the highest-grossing sound film: brief.bismarckanalysis.com/p/disneys-boar…

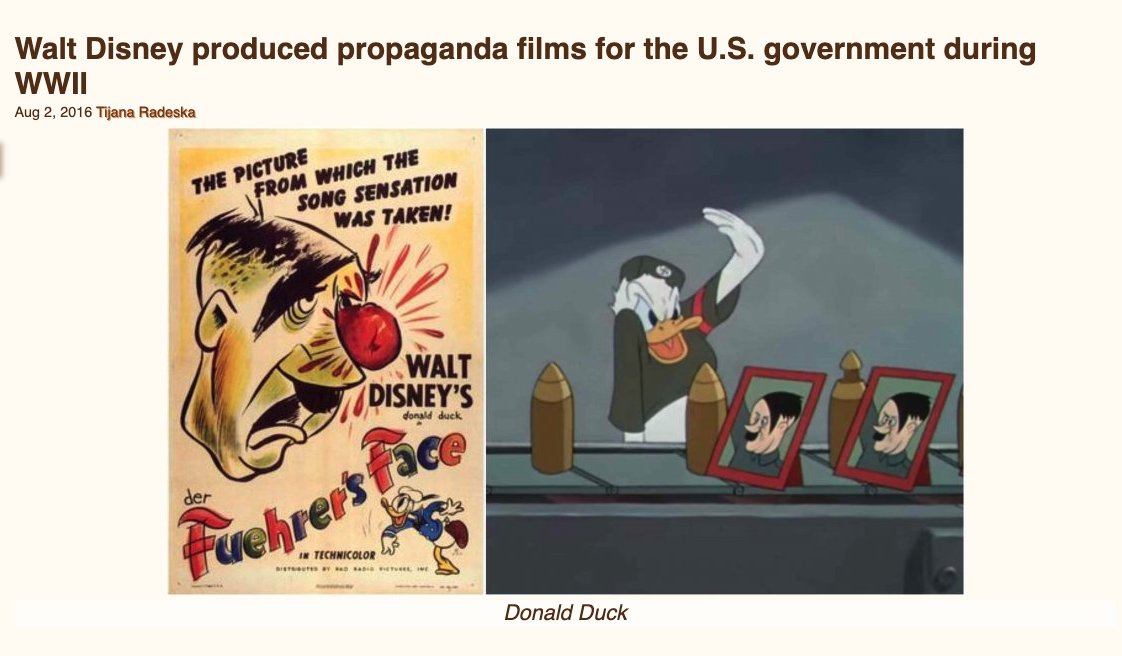

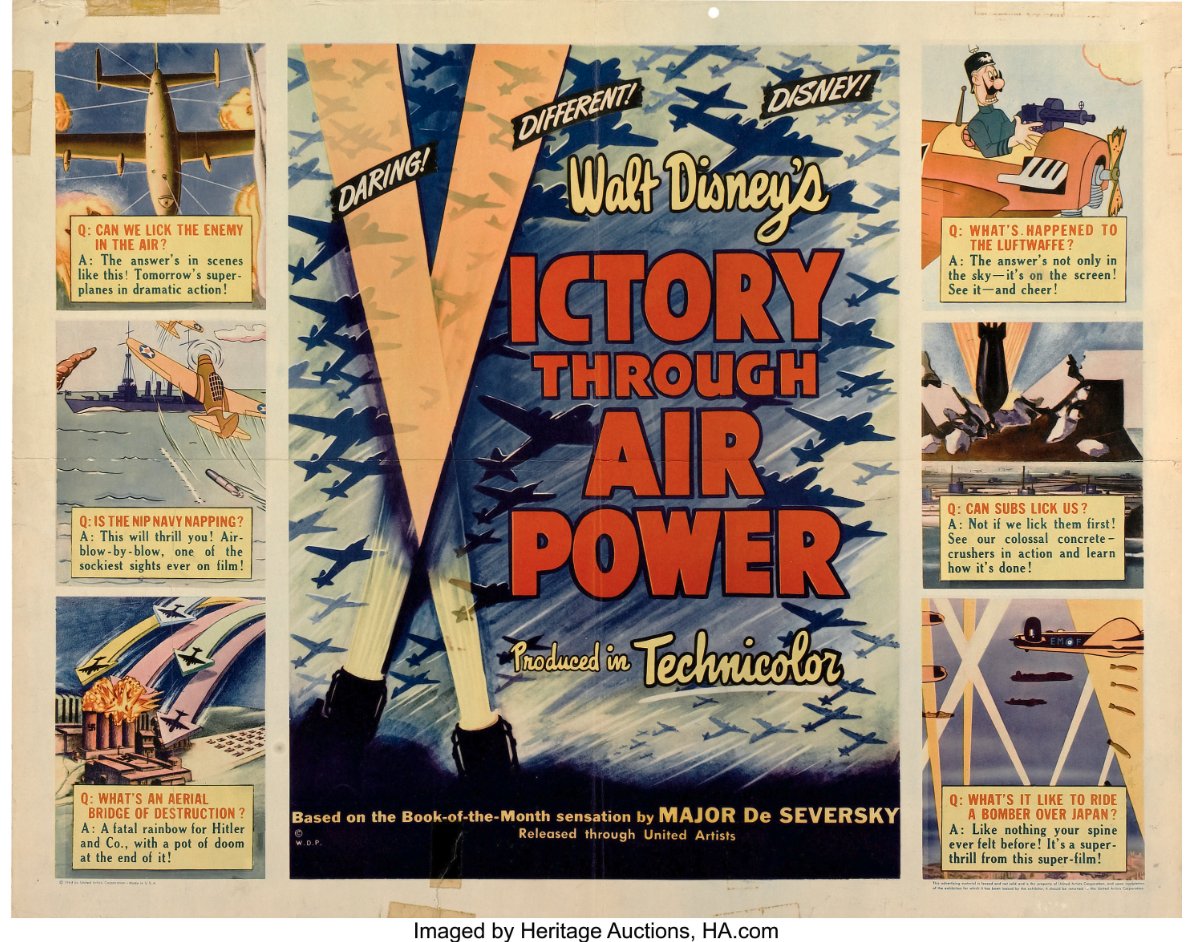

But didn't everyone make animated WWII propaganda? In fact, no. Only two countries succeeded at releasing feature-length animated wartime propaganda films: the United States and Japan.

How come? Because back then…

How come? Because back then…

Animation wasn’t just an art, it was a cutting-edge industrial process requiring specialized equipment and hundreds of skilled laborers to mass-produce frames of animation.

Tens of thousands of frames had to be perfect for a complete film. Animation was high-tech *industry.*

Tens of thousands of frames had to be perfect for a complete film. Animation was high-tech *industry.*

What we think of as animation is Disney’s innovation in “cel” animation i.e. transparent celluloid sheets that made better animation easier, plus other new techniques with camera depth.

Snow White required >250,000 cels and >500,000 photographs of cels.

Snow White required >250,000 cels and >500,000 photographs of cels.

Like any new industry, it was risky, capital-intensive, and only a live player could pull it off.

Walt Disney budgeted 10x a short animated film budget for Snow White, then ended up mortgaging his house and almost bankrupting the company when costs spiraled to 10x of *that.*

Walt Disney budgeted 10x a short animated film budget for Snow White, then ended up mortgaging his house and almost bankrupting the company when costs spiraled to 10x of *that.*

Disney spent 100x the baseline budget for animation on Snow White ($31 million in 2023$).

Hollywood thought him mad. His own wife and brother tried to dissuade him.

But it was a revolutionary technical, cultural, and financial success. Which others tried reverse-engineering…

Hollywood thought him mad. His own wife and brother tried to dissuade him.

But it was a revolutionary technical, cultural, and financial success. Which others tried reverse-engineering…

Like any new industry, there was a shortcut to replicating the live player’s work: state-directed investment as part of industrial policy.

And that’s exactly what the Japanese military did during World War II, when it decided to support, fund, and direct Japanese animation.

And that’s exactly what the Japanese military did during World War II, when it decided to support, fund, and direct Japanese animation.

In 1930s Japan, animation was dominated by foreign films, especially Disney. They had sound/color while Japanese animation was silent and monochrome.

Japanese animators were lone craftsmen with little funds or distribution. Often their work wasn’t even screened in theaters.

Japanese animators were lone craftsmen with little funds or distribution. Often their work wasn’t even screened in theaters.

When WWII started, the Japanese military government decided to change this. American animation was banned.

The government forced small animator ateliers to merge and consolidate into large studios, then directed them to invent a new style of animation with Japanese aesthetics.

The government forced small animator ateliers to merge and consolidate into large studios, then directed them to invent a new style of animation with Japanese aesthetics.

Celluloid was expensive! This deliberate consolidation allowed pooling of resources, larger crews, and division of labor, just like Disney.

This wasn’t coincidental either: they thought Disney animation was military-grade propaganda technology that Japan needed to win WWII.

This wasn’t coincidental either: they thought Disney animation was military-grade propaganda technology that Japan needed to win WWII.

For Momotaro 2, the military paid for a million-dollar production budget that supported 80 staff, and kept the director from being drafted.

They even handled distribution, paying for Momotaro 1 to be screened in 100 cinemas.

Both were unprecedented for Japanese animation.

They even handled distribution, paying for Momotaro 1 to be screened in 100 cinemas.

Both were unprecedented for Japanese animation.

Like the U.S. and Disney, Japan's military commissioned many animated educational films for military training, as well as short propaganda films.

Only wartime governments were willing to invest so much in animation. No private customer was. But this funding built the industry.

Only wartime governments were willing to invest so much in animation. No private customer was. But this funding built the industry.

After the war, this advanced industrial propaganda machine wasn’t destroyed. It was repurposed for civilian uses!

The animators who made Momotaro, including Kenzo Masaoka and Mitsuyo Seo, would immediately in 1945 found what would become Japan’s key post-war animation studio…

The animators who made Momotaro, including Kenzo Masaoka and Mitsuyo Seo, would immediately in 1945 found what would become Japan’s key post-war animation studio…

Toei Animation made the first anime film screened in the U.S. and employed Osamu Tezuka, the “godfather of manga” and creator of the first anime TV series shown in the U.S.

Toei also animated Transformers, Digimon, Dragonball Z, Sailor Moon… & launched Hayao Miyazaki’s career.

Toei also animated Transformers, Digimon, Dragonball Z, Sailor Moon… & launched Hayao Miyazaki’s career.

Tezuka, “Japan’s Walt Disney,” not only worked at Toei. He was inspired to enter animation after he saw Momotaro in 1945 as a boy!

All the later traditions of knowledge in animation can be traced back to this early period of innovation and scale-up under military patronage.

All the later traditions of knowledge in animation can be traced back to this early period of innovation and scale-up under military patronage.

Anime today is 76% of U.S. comic sales. 40 million Americans have a Crunchyroll account (anime streaming).

Yet anime originates in imperial Japanese military funding of an unprecedented proof-of-concept for anti-American war propaganda. It was the Manhattan Project for anime.

Yet anime originates in imperial Japanese military funding of an unprecedented proof-of-concept for anti-American war propaganda. It was the Manhattan Project for anime.

Manga or Japanese cartoons obviously predate anime, but it was exports of anime that drove interest in manga abroad, not the other way around.

Japan’s animated films/series were bought by networks worldwide for a simple reason: it was plentiful, quality, and cheap!

Japan’s animated films/series were bought by networks worldwide for a simple reason: it was plentiful, quality, and cheap!

World War II was a brief window where the new technology of animation lined up with the propaganda needs of governments, but only the U.S. and Japan took the opportunity to invest heavily in the industry.

And so 80 years later, we still watch American or Japanese cartoons.

And so 80 years later, we still watch American or Japanese cartoons.

Japanese success in video games is a cousin, not a son, of its animation.

Nintendo alone saved video game consoles from an early death after Atari and the early 1980s video game bubble.

Part of the story was the aesthetic and business sense of Nintendo’s execs and designers…

Nintendo alone saved video game consoles from an early death after Atari and the early 1980s video game bubble.

Part of the story was the aesthetic and business sense of Nintendo’s execs and designers…

…but the other was simply that Japan was an advanced industrial economy able to manufacture quality cheap electronic components.

Quality cheap electronics were why CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi took Nintendo, originally a toy company, into electronic entertainment in the first place.

Quality cheap electronics were why CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi took Nintendo, originally a toy company, into electronic entertainment in the first place.

This suggests the core reason why some countries have influence in global popular culture today and others do not: early industrialization + persistent industrial policy.

Japan industrialized very early, before WW1. It was thus capable of competing with Disney from the get-go.

Japan industrialized very early, before WW1. It was thus capable of competing with Disney from the get-go.

By the 1980s, Japan was still on the industrial upswing while America and Europe were already stagnating.

Japanese live players were prepared to seize the concept of video games, pairing cheap electronics with their own designers from the manga industry, and make it their own.

Japanese live players were prepared to seize the concept of video games, pairing cheap electronics with their own designers from the manga industry, and make it their own.

Modern popular culture doesn’t follow aesthetic or cultural logic, but the logic of industrial production and export!

This is because popular cultural products are not only aesthetic concepts, but also always technological products mass-produced by industrial institutions.

This is because popular cultural products are not only aesthetic concepts, but also always technological products mass-produced by industrial institutions.

Governments and live players can intervene to fund and build industries that produce and export cultural products, where none existed before, thus altering the global cultural landscape.

If they don’t, or they fail, a less influential cultural industry develops, if at all…

If they don’t, or they fail, a less influential cultural industry develops, if at all…

What about France, Germany, Britain, or the Soviet Union? Weren’t they also industrialized countries? Why don’t they export animation and video games?

The answer is each one failed at a different stage of the industrial policy needed to export pop culture successfully.

The answer is each one failed at a different stage of the industrial policy needed to export pop culture successfully.

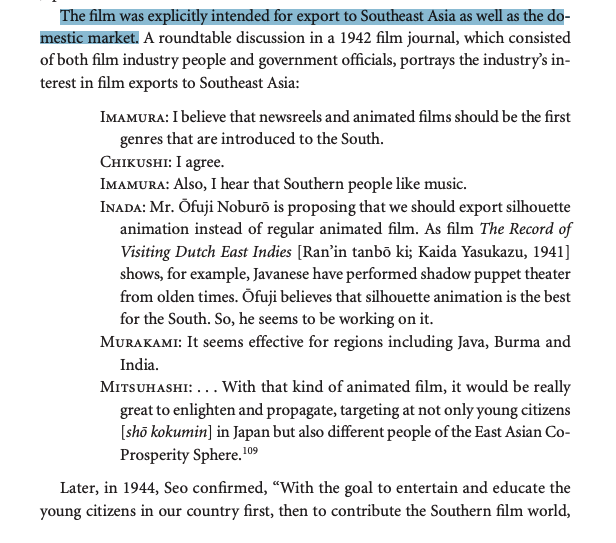

First, these countries never really pursued an export strategy. The Japanese aimed to export their animation to Japan's occupied colonies in Asia from day one.

Even after the war, Toei Animation was capitalized on the basis it would also export to China’s huge audience.

Even after the war, Toei Animation was capitalized on the basis it would also export to China’s huge audience.

The USSR was an exception. Its state animation company, Soyuzmultfilm, exported to the East Bloc.

But like all things Soviet, these were arguably subpar products, and Soviet cartoons never really pierced the Iron Curtain during the Cold War for ideological reasons.

But like all things Soviet, these were arguably subpar products, and Soviet cartoons never really pierced the Iron Curtain during the Cold War for ideological reasons.

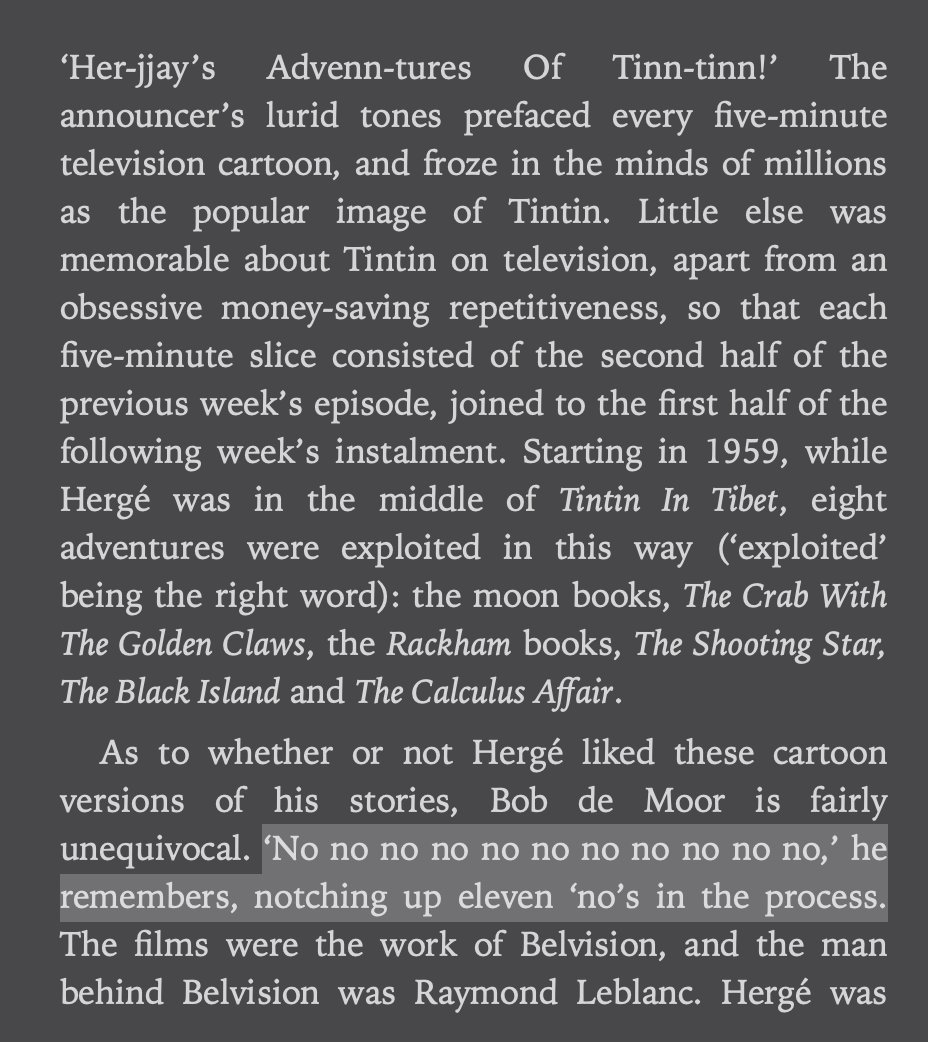

France had a rich tradition in cartoons like Tintin. But France was invaded by Germany three years after Disney released Snow White. No industrial policy after that.

After the war, France’s animation industry was so weak that its attempt at Tintin on TV was a catastrophe.

After the war, France’s animation industry was so weak that its attempt at Tintin on TV was a catastrophe.

In WWII, Germany actually had a state animation company tasked with replicating Disney’s success!

It however started late and failed before the war ended.

The only Disney-style animated film ever made by Nazi Germany is also on YouTube:

It however started late and failed before the war ended.

The only Disney-style animated film ever made by Nazi Germany is also on YouTube:

Britain seemed to have had all the ingredients for success, but simply failed to care about animation at all. Perhaps they just preferred to watch Disney.

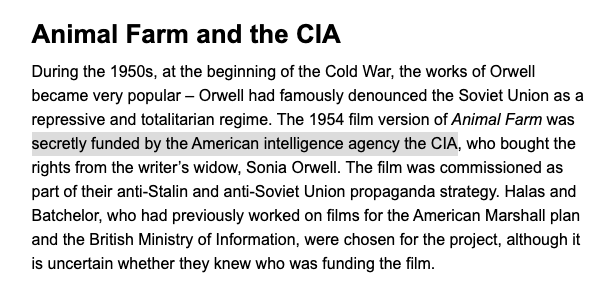

Britain's first animated feature film, 1954’s Animal Farm, was directed and funded by the CIA.

Britain's first animated feature film, 1954’s Animal Farm, was directed and funded by the CIA.

Popular cultural products are powerful because they quietly shape people’s moral values and beliefs, especially as children.

But this means that any strategy to alter popular values through popular culture is necessarily an industrial strategy, not an aesthetic one.

But this means that any strategy to alter popular values through popular culture is necessarily an industrial strategy, not an aesthetic one.

Popular culture or values will never change by critiquing them intellectually or aesthetically, but only by creating new engines of industrial cultural production.

The lesson is: if you don’t control the means of production, you won’t control the means of value formation!

The lesson is: if you don’t control the means of production, you won’t control the means of value formation!

In the future, I predict India will fail to make an impact on global popular culture, due to its lack of industry. China will fail due to ideological incompatibility.

Japan is now stagnating too, along with Europe, though the U.S. and Japan both have incumbent advantage.

Japan is now stagnating too, along with Europe, though the U.S. and Japan both have incumbent advantage.

But I predict South Korea will have a surprising impact on popular culture in the future. It is not ideologically disfavored by the U.S. or Europe and is still a growing center of industry.

We will see more of K-pop, Squid Game, and so on. New popular cultural products as well.

We will see more of K-pop, Squid Game, and so on. New popular cultural products as well.

In conclusion: popular culture is a function of technological/industrial capacity, with deliberate policy by live players or governments to export it.

Japan’s pop culture is influential globally because of industrial policy going back to WWII—not [only] because it’s kawaii.

Japan’s pop culture is influential globally because of industrial policy going back to WWII—not [only] because it’s kawaii.

If you enjoyed this thread, follow me!

And remember to subscribe to @bismarckanlys Brief, where we analyze and investigate similar questions of industry, technology, and institutions.

This thread was inspired by our Brief on Disney: brief.bismarckanalysis.com/p/disneys-boar…

And remember to subscribe to @bismarckanlys Brief, where we analyze and investigate similar questions of industry, technology, and institutions.

This thread was inspired by our Brief on Disney: brief.bismarckanalysis.com/p/disneys-boar…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh