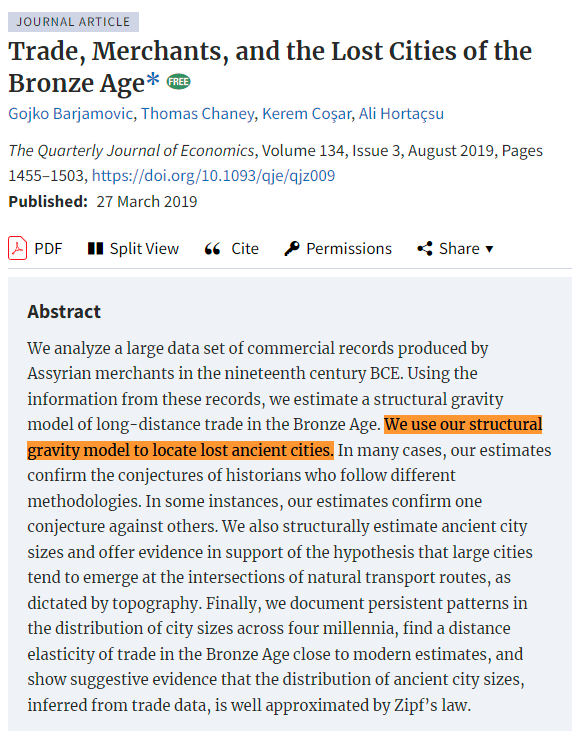

Remember that time economists used a gravity model to find ancient lost cities from the Bronze Age?

If you do or you don't, check out this thread🧵

If you do or you don't, check out this thread🧵

The authors gained access to a collection of almost 12,000 deciphered and edited texts that were excavated primarily at the archaeological site of Kültepe, ancient Kaneš.

The ruins (pictured) are located in central Turkey, in the province of Kayseri.

The ruins (pictured) are located in central Turkey, in the province of Kayseri.

The texts look like this.

They were inscribed on clay tablets in the Old Assyrian dialect of Akkadian in cuneiform by ancient Assyrian merchants, business partners, and their family members.

This tablet is dated to between 1930 and 1775 B.C.

They were inscribed on clay tablets in the Old Assyrian dialect of Akkadian in cuneiform by ancient Assyrian merchants, business partners, and their family members.

This tablet is dated to between 1930 and 1775 B.C.

The tablets were all from between 1930 and 1775 B.C., and 90% of the sample came from just one generation of traders, between 1895 and 1865 B.C.

The reason is that Kaneš experienced a major fire in 1840 B.C. and the commercial archives in the city were sealed off.

The reason is that Kaneš experienced a major fire in 1840 B.C. and the commercial archives in the city were sealed off.

Tablets were largely business letters, shipment documents, accounting records, seals, and contracts.

A typical shipment document or expense account in which a merchant would inform partners about their cargo and expenses would read like this:

A typical shipment document or expense account in which a merchant would inform partners about their cargo and expenses would read like this:

The tablets are spread across the world in museums and institutions, but many have been transcribed.

The transcribed ones mentioned 79 cities distributed across modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey and 2,806 mentioned at least two Anatolian city names simultaneously, like so:

The transcribed ones mentioned 79 cities distributed across modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey and 2,806 mentioned at least two Anatolian city names simultaneously, like so:

That tablet identified three shipments: Durhumit to Kaneš, Kaneš to Wahšušana, and Durhumit to Wahšušana.

So the itinerary is A→B→C, and there were 227 of these, with 391 examples of travel between city pairs.

Specifically, 25 city pairs: 15 known (gray), 10 lost (black).

So the itinerary is A→B→C, and there were 227 of these, with 391 examples of travel between city pairs.

Specifically, 25 city pairs: 15 known (gray), 10 lost (black).

Using trade among known cities, they estimated the distance elasticity of trade (how sensitive trade btwn cities is to the distance btwn them), so they could estimate the prbblity of shipments from city i to city j given their distance

Thus, probable locations for 10 lost cities

Thus, probable locations for 10 lost cities

These estimates largely concurred with those of historians, and since the historians' conjectures weren't used in the model, this suggests people should start pursuing those estimations.

In fact, this modeling exercise might help to decide among the different proposals made by historians.

But the authors weren't done. They supplemented their analysis with data from merchant itineraries. For example, consider this letter:

That letter was submitted to the Assyrian port authorities at Kaneš from emissaries in Wahšušana, and it described how missives would travel through two different routes:

Wahšušana→Ulama→Purušhaddum

W→Šalatuwar→P

But only Wahšušana, Ulama, and Šalatuwar are known cities.

Wahšušana→Ulama→Purušhaddum

W→Šalatuwar→P

But only Wahšušana, Ulama, and Šalatuwar are known cities.

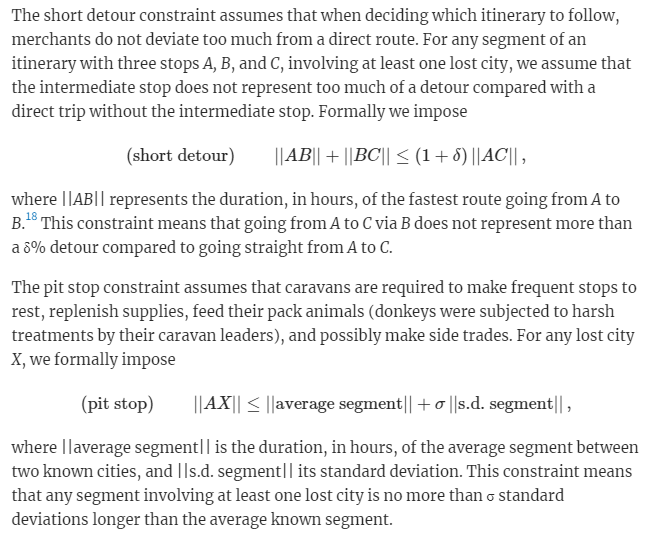

Using every multistop itinerary, a model with just two constraints offers a lot of info. The constraints are simple:

1. When deciding itineraries, merchants like direct routes.

2. Caravans have to make stops to rest, replenish supplies, feed pack animals, and make side trades.

1. When deciding itineraries, merchants like direct routes.

2. Caravans have to make stops to rest, replenish supplies, feed pack animals, and make side trades.

With estimates constrained to regions that are admissible given those constraints (dashed lines), the locations of the newly-identified lost cities are now more certain!

With the exception of Purušhaddum.

With the exception of Purušhaddum.

But how do we know this method works?

Easy! Just lose known cities and see if the method rediscovers them.

As the picture shows, the average distance between estimated and known city locations wasn't huge. In fact, estimates were a median of 33km away (mean = 40km).

Easy! Just lose known cities and see if the method rediscovers them.

As the picture shows, the average distance between estimated and known city locations wasn't huge. In fact, estimates were a median of 33km away (mean = 40km).

This method also helps to identify the names of sites that people have continued living in, like Kırşehir Kalehöyük, which might have been located under where the Alaaddin Mosque and a high school were later built.

There are other interesting findings here, too.

Consider this: geography has deep and persistent impacts on the economy of the area, and cities tend to show up where there are "natural roads".

Consider this: geography has deep and persistent impacts on the economy of the area, and cities tend to show up where there are "natural roads".

And, modern cities are larger when nearby ancient cities were estimated to be larger as well.

The deep geographic reasons for cities to crop up in certain locations are still powerful forces today!

The deep geographic reasons for cities to crop up in certain locations are still powerful forces today!

There you have it: economists might have discovered the locations of ancient lost cities from the Bronze Age, and supported a number of other fun facts while they were at it.

Only time will tell if these discoveries end up being true 🤞

Only time will tell if these discoveries end up being true 🤞

Link:

The model the authors used was the gravity model: the workhorse model of trade.

Just as all roads lead to Rome, many trade theorists have derived the gravity equation for trade: academic.oup.com/qje/article/13…

cepr.org/voxeu/columns/…

The model the authors used was the gravity model: the workhorse model of trade.

Just as all roads lead to Rome, many trade theorists have derived the gravity equation for trade: academic.oup.com/qje/article/13…

cepr.org/voxeu/columns/…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh