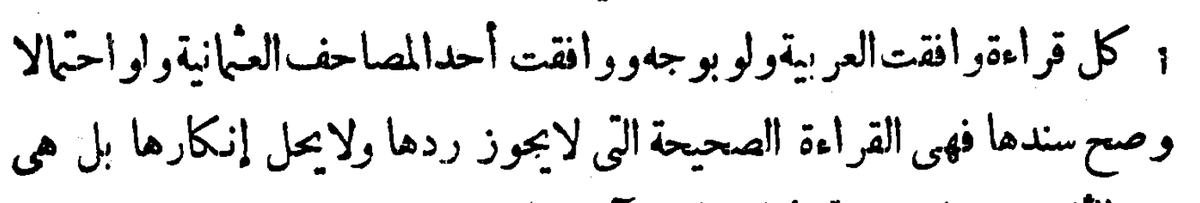

The Arabic letter rāʾ is a bit of a puzzle. In the Islamic era, and even in the centuries leading up to the Islamci Era, the shape of the rāʾ is clearly distinct from the dāl...

But this was not always the case!

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

But this was not always the case!

#ArabicLetterofTheWeek

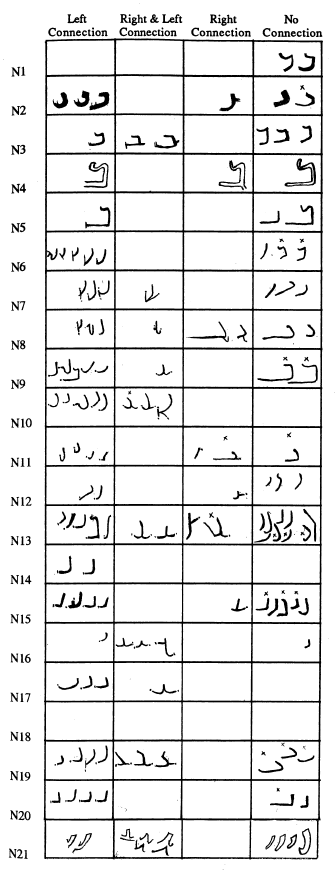

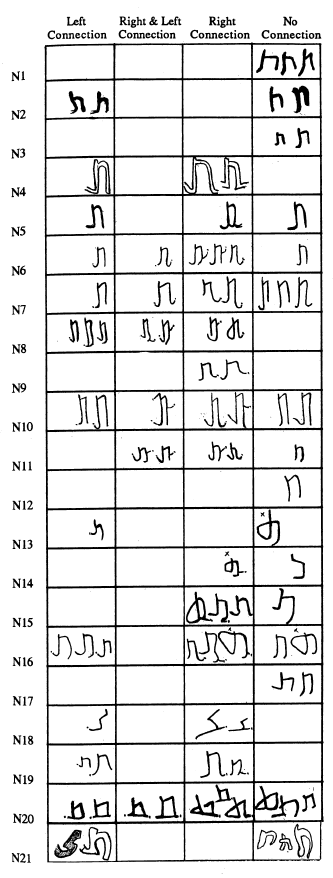

In the Aramaic script (and by extension the Nabataean Aramaic script -- the ancestor of the Arabic script) the <d> and <r> signs have always been quite similar, but were originally distinct. This is also the reason why the Hebrew script's ד <d> and ר <r> look so damn similar.

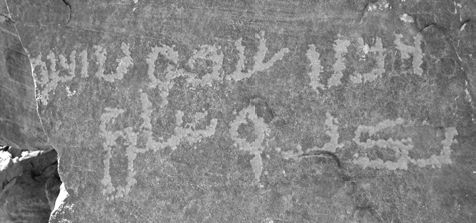

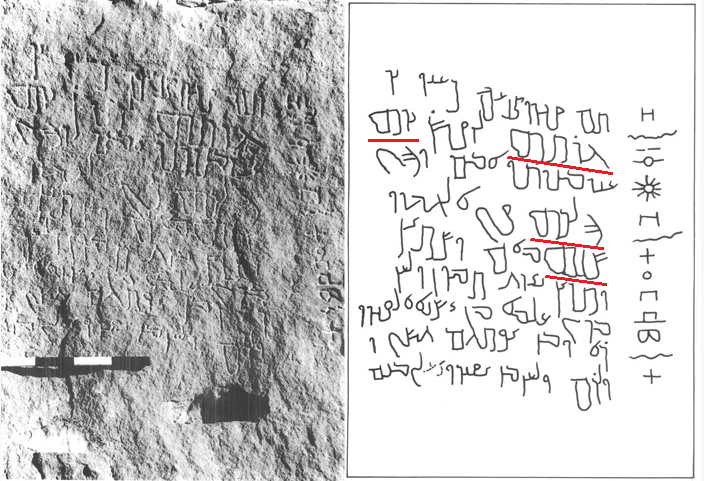

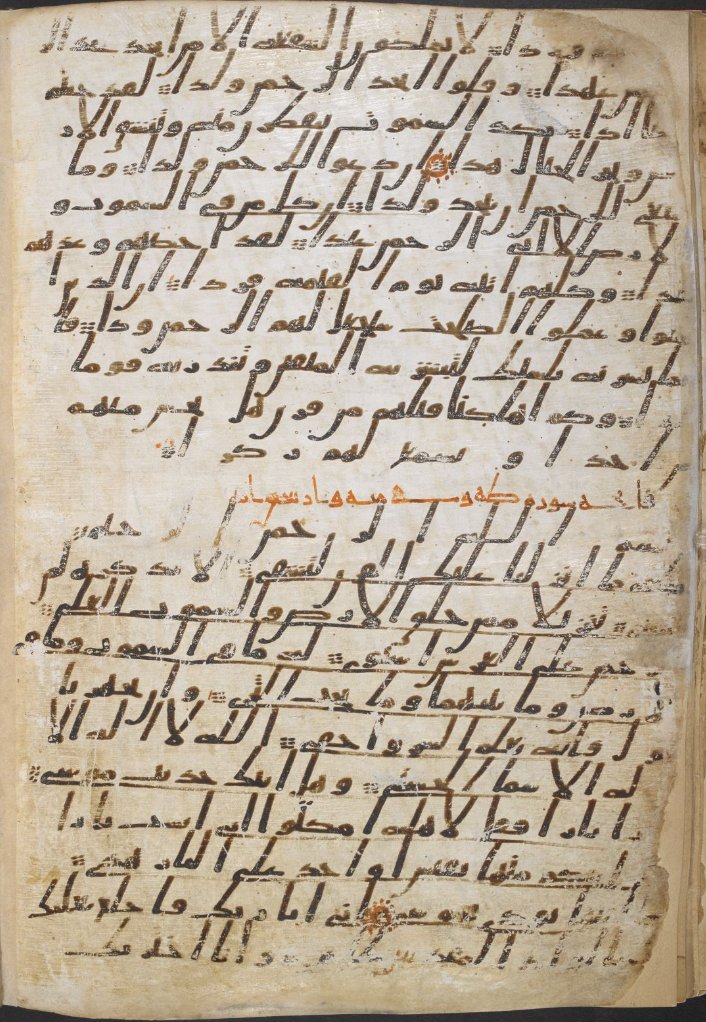

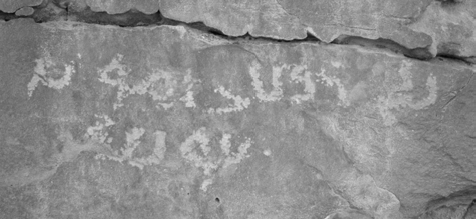

But in Nabataean Aramaic proper, even from its very earliest stage, these two signs are basically indistinguishable. For example this inscription reads

<qbrʾ dnh> "this grave", but as you can see the d and r are simply the same straight line with a little u at the top.

<qbrʾ dnh> "this grave", but as you can see the d and r are simply the same straight line with a little u at the top.

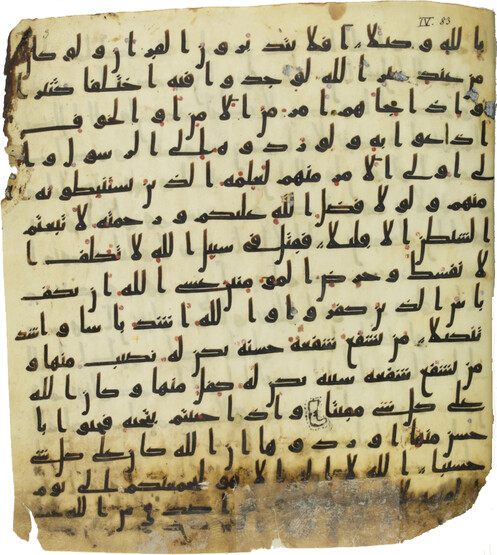

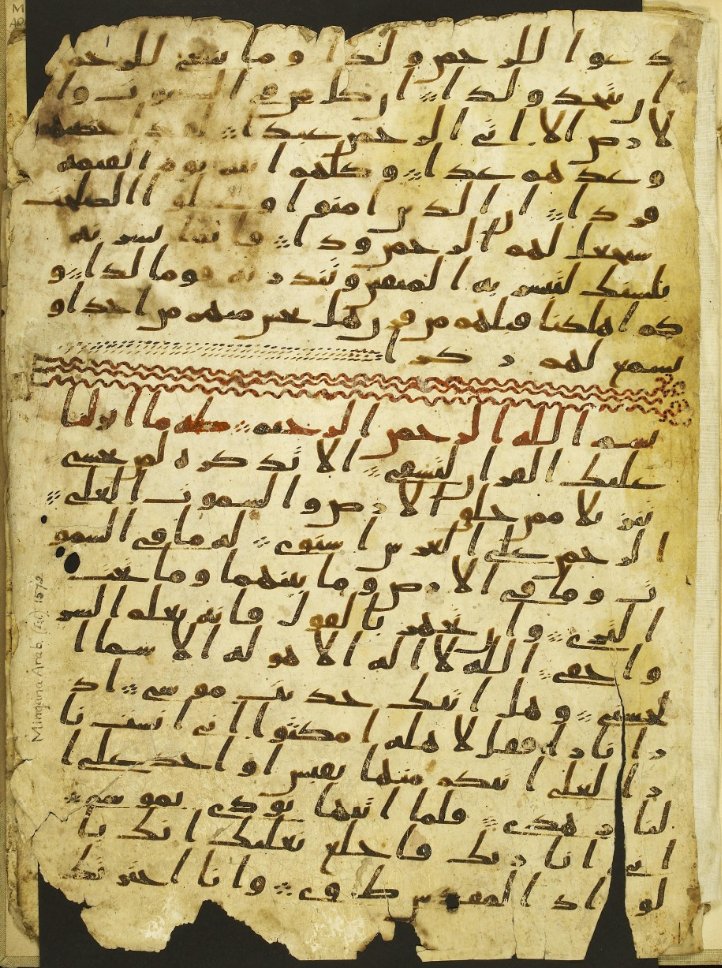

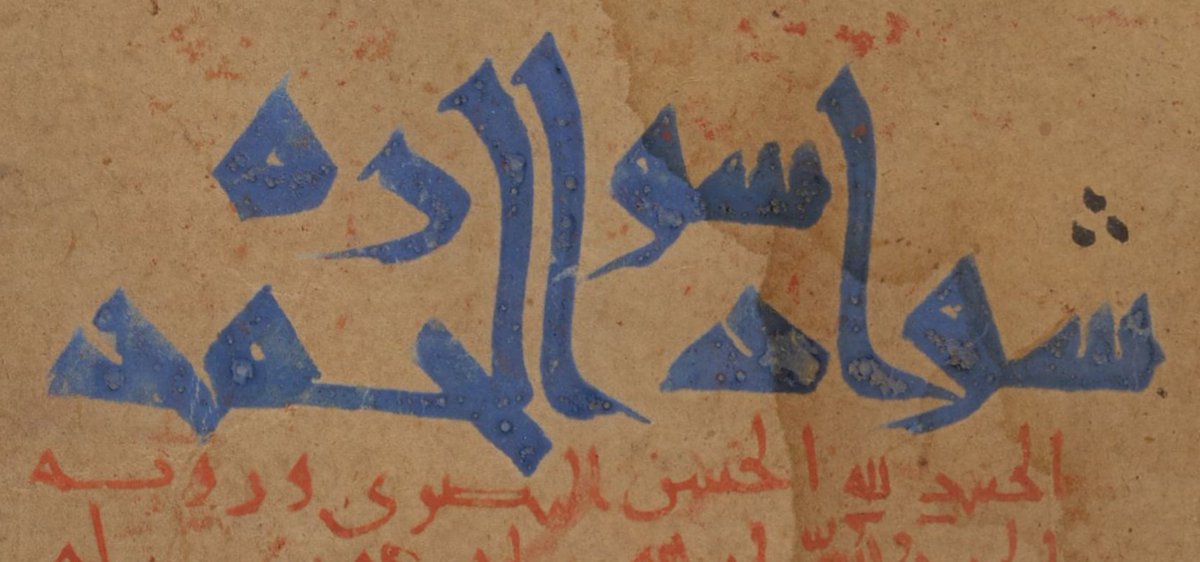

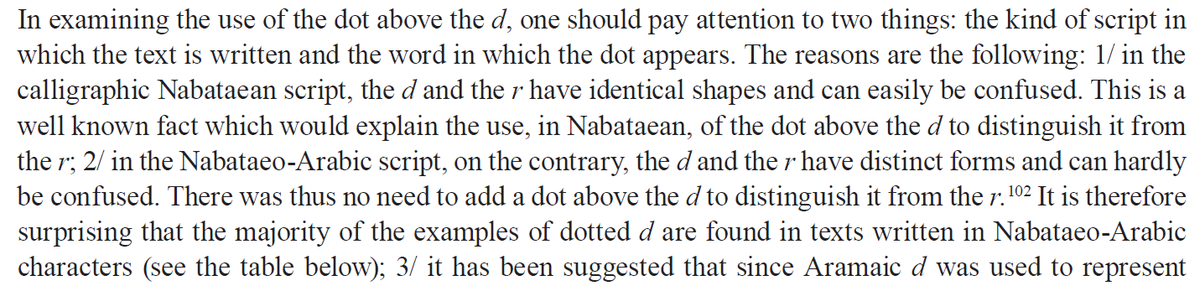

This is very annoying, of course. So at some point the Nabataean writers came to agree, and decided to place a dot on top of the dāl to distinguish it from the rāʾ, surprisingly we see this most in inscriptions where the <d> and <r> actually have distinct shapes!

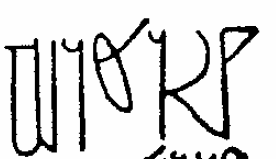

<bly dkyr ...>

<bly dkyr ...>

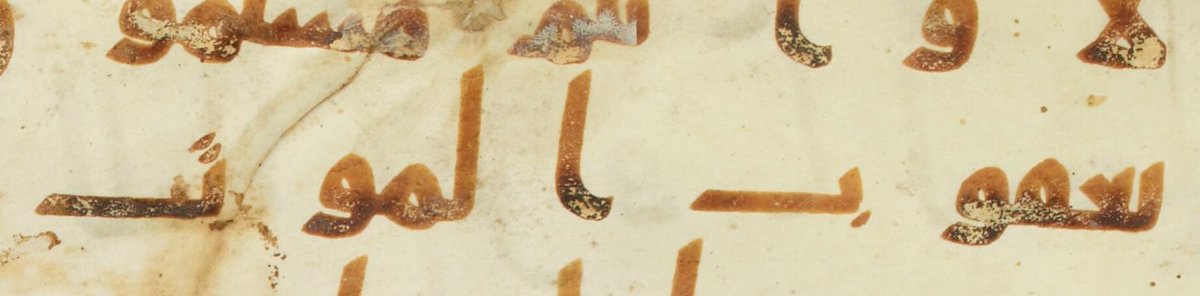

And that is the real mystery: Somewhere in the history of the Nabataean script, the shape of the <r> and <d> demerge. They really seem to have been indistinguishable, but in the centuries leading up to Islam, become distinguished again.

This is especially striking because the overall trend of the Nabataean script in this period is to merge more and more shapes with one:

<q> with <f>

<n> with <b>

<y> with <t>

But <r/d> splits into <r> and <d>. Why? and How? I don't think anyone has a satisfying answer yet.

<q> with <f>

<n> with <b>

<y> with <t>

But <r/d> splits into <r> and <d>. Why? and How? I don't think anyone has a satisfying answer yet.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter