This piece at @WorksInProgMag on the sources of the baby boom is fascinating, but, I think, incorrect, or at least quite incomplete.

They argue that technology innovation (washing machines, antibiotics) caused the baby boom. This, I think, is wrong. worksinprogress.co/issue/understa…

They argue that technology innovation (washing machines, antibiotics) caused the baby boom. This, I think, is wrong. worksinprogress.co/issue/understa…

To start with, note that there are some cases where antibiotics definitely DID cause baby booms. Mongolia under the Soviet antibiotic revolution is a paradigmatic case: demographic-research.org/articles/volum…

In Mongolia's case, widespread venereal disease caused widespread childlessness. Antibiotics fixed the venereal disease, fertility jumped up. Straightforward story, I don't think anybody really contests this at this point in time.

But is that what happened in America?

To some extent, yes! Syphillis case incidence fell DRAMATICALLY 1943-2000.

cdc.gov/std/statistics…

To some extent, yes! Syphillis case incidence fell DRAMATICALLY 1943-2000.

cdc.gov/std/statistics…

However, syphilis incidence actually *rose* 1941-1943. Here's Massachusetts share of deaths of syphilis 1842-2000. As you can see, there was a big INCREASE in syphilis deaths deaths 1934-1943, the EXACT PERIOD the baby boom was kicking off.

Had a long interruption, back now!

So, it doesn't *seem* to me like antibiotic prevalence in the US increased before/during the baby boom kickoff. It looks like they really got going *after* the kickoff. Maybe made it a bigger boom, but didn't launch it.

So, it doesn't *seem* to me like antibiotic prevalence in the US increased before/during the baby boom kickoff. It looks like they really got going *after* the kickoff. Maybe made it a bigger boom, but didn't launch it.

Moreover, their specific argument is that maternal mortality fell more in STATES with bigger baby booms.

Okay, more-or-less true.

But it doesn't hold up across countries. A lot of countries with much bigger declines in maternal mortality had smaller baby booms.

Okay, more-or-less true.

But it doesn't hold up across countries. A lot of countries with much bigger declines in maternal mortality had smaller baby booms.

Within demography generally one observed fact has been that Baby Boom Size is proportional to Time Since Transition; i.e. booms were smaller and later in countries with more RECENT fertility transitions. This empirical trend has invited culturalist accounts.

Basically the argument being something cultural motivated a baby boom, but places with recent memories of undesirably high fertility were less responsive to that ideational shock.

I don't necessarily buy it, but it's a better cross-country explanation than the antibiotic story.

I don't necessarily buy it, but it's a better cross-country explanation than the antibiotic story.

Now, a key piece of evidence marshalled is that Amish fertility 1930-1960 follows a similar general trend as non-Amish, and the Amish shared in the antibiotic revolution despite general primitivism.

But this evidence is actually unconvincing, because....

But this evidence is actually unconvincing, because....

I've done a lot of work on Amish demography and, spoiler, Amish fertility rates boom/bust in tandem with general American fertility rates throughout the 20th century, even in the last 20 years.

https://twitter.com/lymanstoneky/status/1435724686663557120?s=20

Also, I want to empirically contest the "Amish baby boom" argument in general. There's considerable debate on this, but the best evidence is maybe a gradual increase across the 1900-1950 Amish birth cohorts, not a baby boom like we see for non-Amish.

More generally, the best quasi-experimental evidence we have ACTUALLY links household appliances to women's work outside the home, NOT fertility. Families bought appliances as part of the transition into the workforce for women. sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

While some people used their washing machines to subsidize more babies, saw the potential to buy household chore completion at a suddenly much cheaper rate as a good reason for the wife to enter the workforce which, spoiler, is not typically pronatal.

What we actually know is that by reducing labor demand at home by automating home tasks, households shifted into non-home labor, NOT expanding the scope of at-home tasks.

In general, I think this piece involves a lot of hopeful thinking about technology, and relies on a lot of now-somewhat-dated publications that over time have not so much been shown to be wrong, but have been shown to be incomplete.

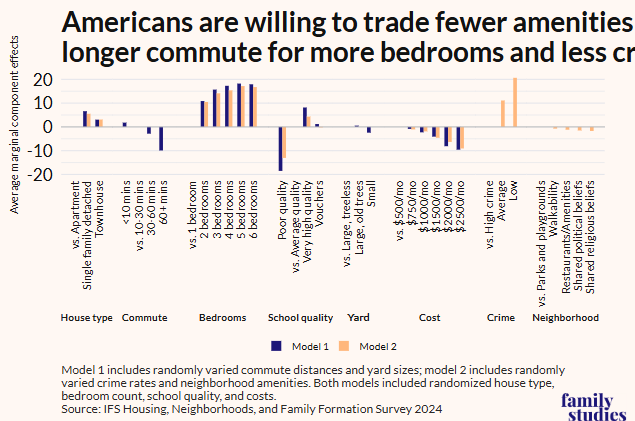

Now the one explanation offered that I 100% buy is the housing one. The Baby Boom absolutely was coextensive and pretty well explained by massive shocks to housing supply and to corresponding household formation. And we have solid empirical evidence of housing-fertility links...

... across innumerable countries, timespans, variables to model housing, etc. Housing is clearly an intimate part of fertility, as literally everybody knows, and the huge postwar housing boom definitely caused part of the Baby Boom. Postwar housing was not just abundant but good!

A lot of people who grew up in housing stock built 1870-1910, i.e. before widespread electrification and universal indoor plumbing, suddenly could suddenly buy houses that are still quality-competitive *today*. It wasn't just housing unit numbers, it was unit size and quality.

The new houses were bigger and better, whole new residential concepts (the car-centric suburban neighborhood!) almost instantaneously became dominant in many places. This was indisputably pronatal.

Finally, besides housing, my personally preferred Baby Boom explanation is this one from @BastienCF @gobbi_paula which suggests cohort accumulated experiences of economic *volatility* impact risk preferences and thus fertility. drive.google.com/file/d/1_aSX9i…

I like this explanation because 1) in efforts to replicate it in other contexts ex-US it has seemed to me to be a pretty good fit, even in contemporary cohorts, 2) it has very clear microfoundations that are well-supported in demography in terms of fertility motivations

So my view of the Baby Boom is that yes perhaps household appliances and antibiotics had a role to play in boosting it a bit, but the major determining factors were economic. Huge housing improvements + large shifts in experienced economic volatility have huge effects.

HT @salimfurth for sharing the article with me, blame him for this thread of Mongolian syphilis content

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh