A thread summarising my talk at #rED23 yesterday on the challenges of applying the science of learning in the classroom 🧵

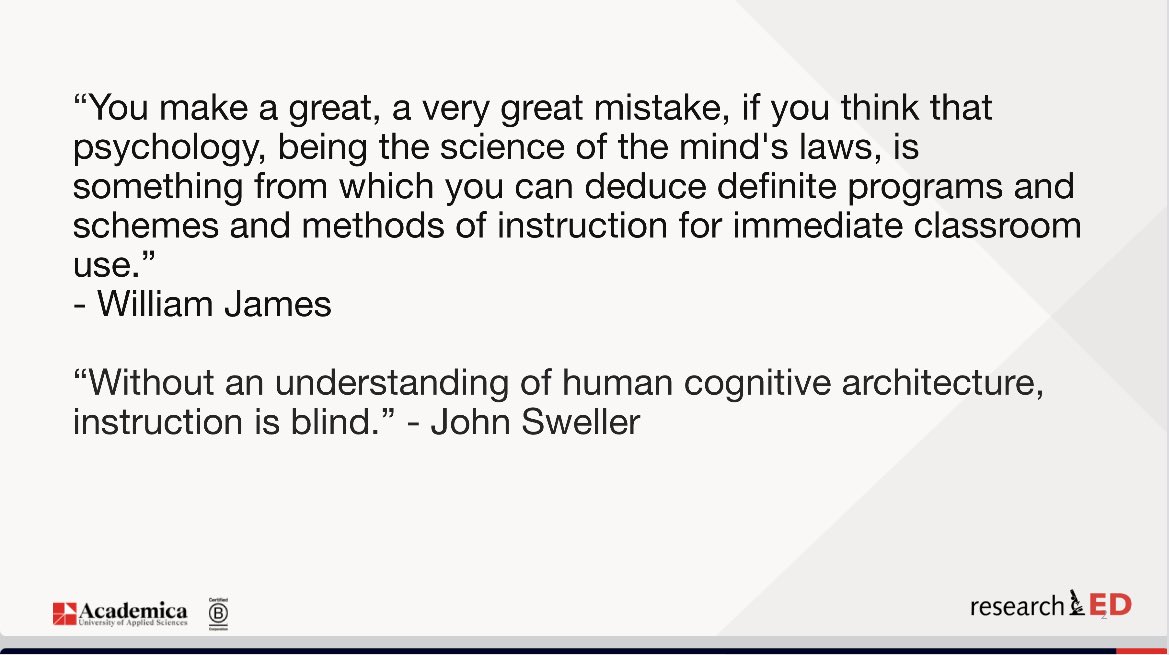

As far back as the 1890s William James cautioned against thinking you can apply the principles of psychology straight into the classroom. However, without an understanding of how the brain learns, planning instruction is suboptimal. I think these two positions encapsulate the interstitial point in which we find ourselves.

What might we mean by an applied science of learning? Here Frederick Reif provides a useful set of principles to consider. (I don’t think we’re anywhere near point 3)

What should an applied science of learning aim to do? It should not only aim to discover how learning happens but more importantly, how to actually use it in the classroom. Donald Stokes notion of Pasteur’s quadrant is a useful way to think about this.

While there may be such thing as a science of learning, we can’t really say there’s such thing as a science of teaching. (Although Mayer would argue there is such thing as a science of instruction.)

Some of the foundational beliefs about how learning happens are not supported by cognitive science and have paved the way for bad ideas in the classroom.

Here are some examples of those bad ideas applied in the classroom courtesy of the brilliant @stoneman_claire’s diabolical time capsule of pedagogical novichok x.com/stoneman_clair…

https://twitter.com/stoneman_claire/status/1520472676795572225

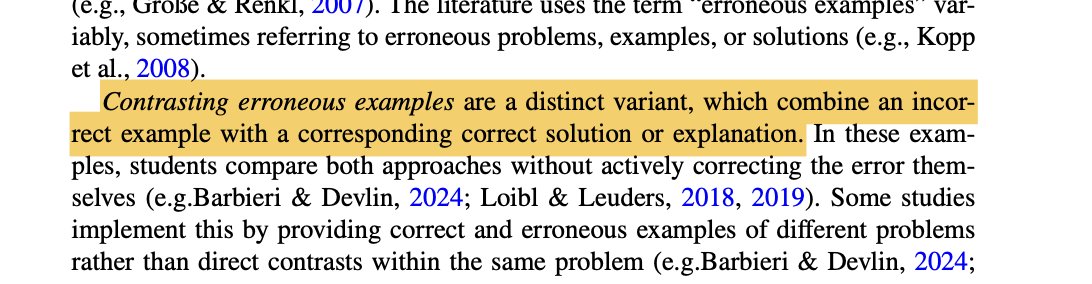

What are some examples of overarching principles of how learning happens? Here I offer some to consider when designing classroom instruction based on cognitive science:

A big challenge is creating a shared understanding of how learning happens. For whatever reason, models of learning based on cognitive science don’t appear to have been a part of many teacher training courses in the past.

Many pseudoscientific beliefs about learning have persisted in the profession. Various studies have shown that as many as 9 out of 10 teachers believe kids learn effectively when content is matched to their learning styles.

A vital challenge now is to create a shared understanding of how learning happens.

A vital challenge now is to create a shared understanding of how learning happens.

As the Perry review (2021) showed, despite a very strong body of evidence from lab settings, a lot of the evidence on cognitive science in practice is not from ecologically valid (realistic) settings.

Thinking more closely about a specific example of applying evidence: Instead of mandating retrieval practice every lesson, subject leaders should be considering implementation in a domain/stage specific way. Among the questions we can ask are:

Applying the science of learning needs careful consideration lest it become a lethal mutation. It shouldn’t be a new form of prescription, robbing teachers of professional agency.

An analogy: It’s not so much paining by numbers as pointillism where instead of simplistic broad brush approach, teachers make much more refined decisions moment to moment based on a sound knowledge of how learning happens.

An analogy: It’s not so much paining by numbers as pointillism where instead of simplistic broad brush approach, teachers make much more refined decisions moment to moment based on a sound knowledge of how learning happens.

Frederick Reif has been asking this question for over 50 years. There is now an ethical imperative for every teacher to have a sound knowledge of how learning happens.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh