Dad | Professor of applied sciences @AcademicaUoAS | PhD @KingsCollegeLon | UNESCO SoL editorial board | Dubliner | Keats devotee | persecuted by an integer

5 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

In 'Sciences of the Artificial', Herbert Simon described an ant's complex, winding path across a beach.

In 'Sciences of the Artificial', Herbert Simon described an ant's complex, winding path across a beach.

A “pattern” isn’t a recipe. It’s a constraint that, if violated, makes the design fail no matter how pretty the surface is. A room can be any style, but violate “Light on Two Sides” and it will feel gloomy anyway.

A “pattern” isn’t a recipe. It’s a constraint that, if violated, makes the design fail no matter how pretty the surface is. A room can be any style, but violate “Light on Two Sides” and it will feel gloomy anyway.

As a general rule, knowledge that's central to the discipline should be retrieved.

As a general rule, knowledge that's central to the discipline should be retrieved.

There are, broadly speaking, two Vygotskys.

There are, broadly speaking, two Vygotskys.

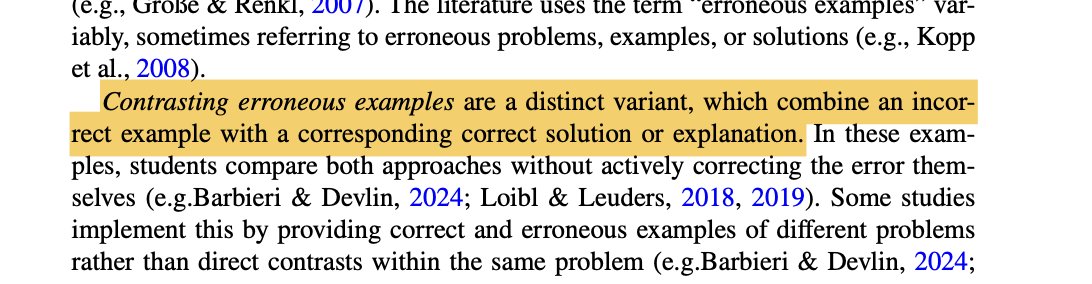

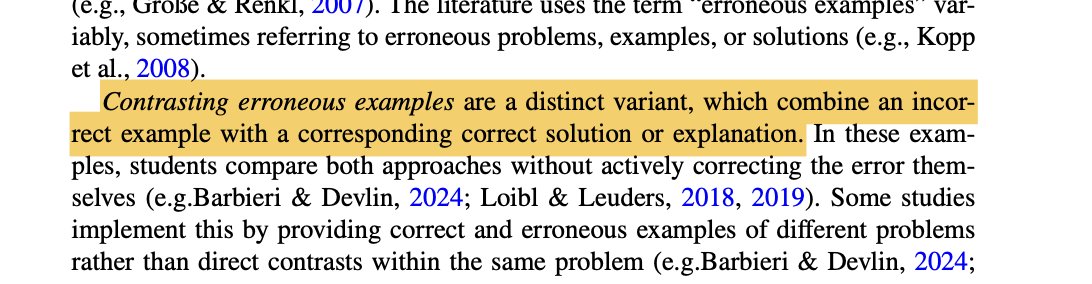

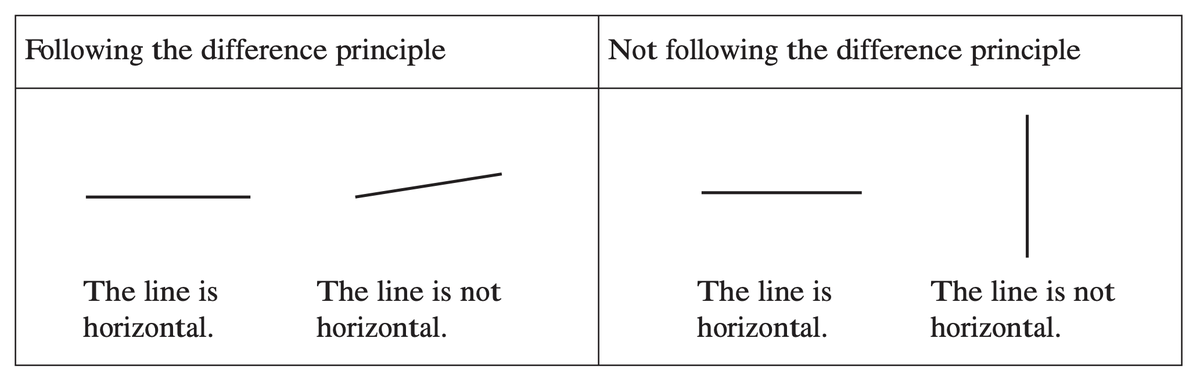

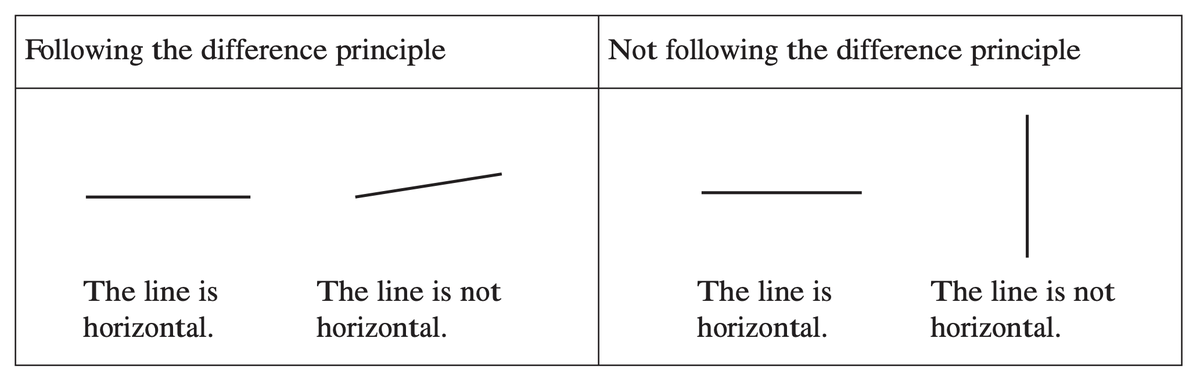

Again I'm reminded of Theory of Instruction here and the idea that we learn what something is by contrasting it with what it isn't.

Again I'm reminded of Theory of Instruction here and the idea that we learn what something is by contrasting it with what it isn't.

Chi’s research revealed that misconceptions are not just small knowledge deficits; they are often coherent yet incorrect frameworks of understanding.

Chi’s research revealed that misconceptions are not just small knowledge deficits; they are often coherent yet incorrect frameworks of understanding.

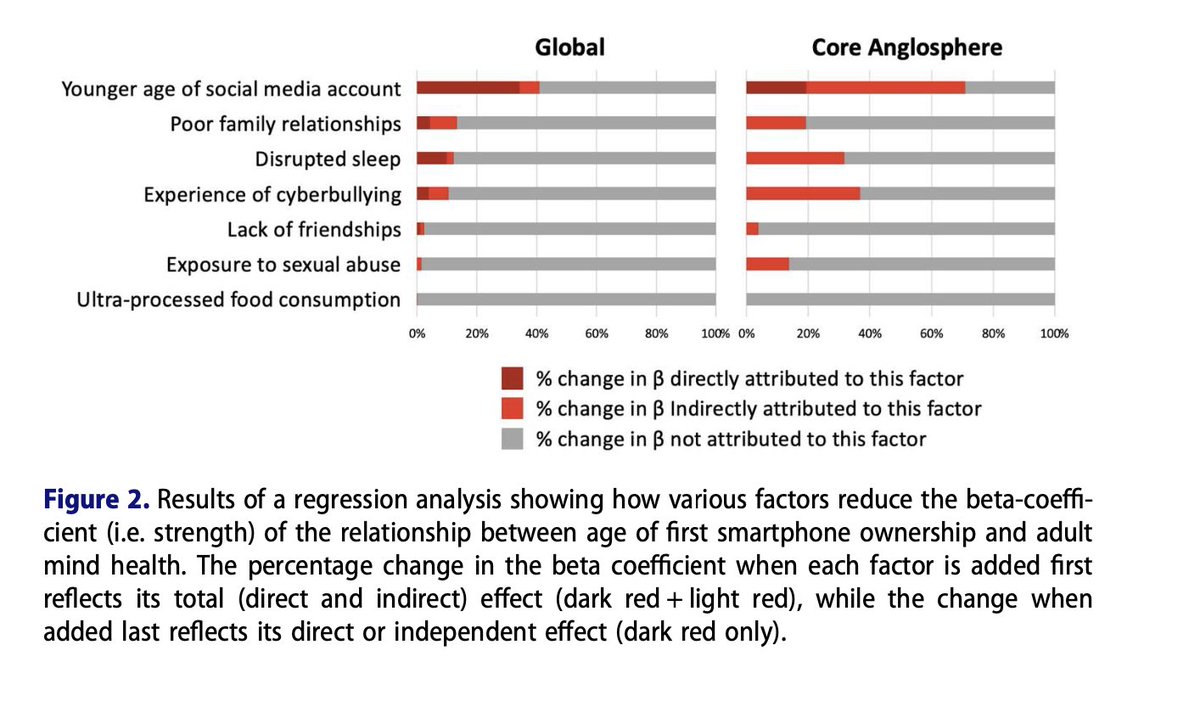

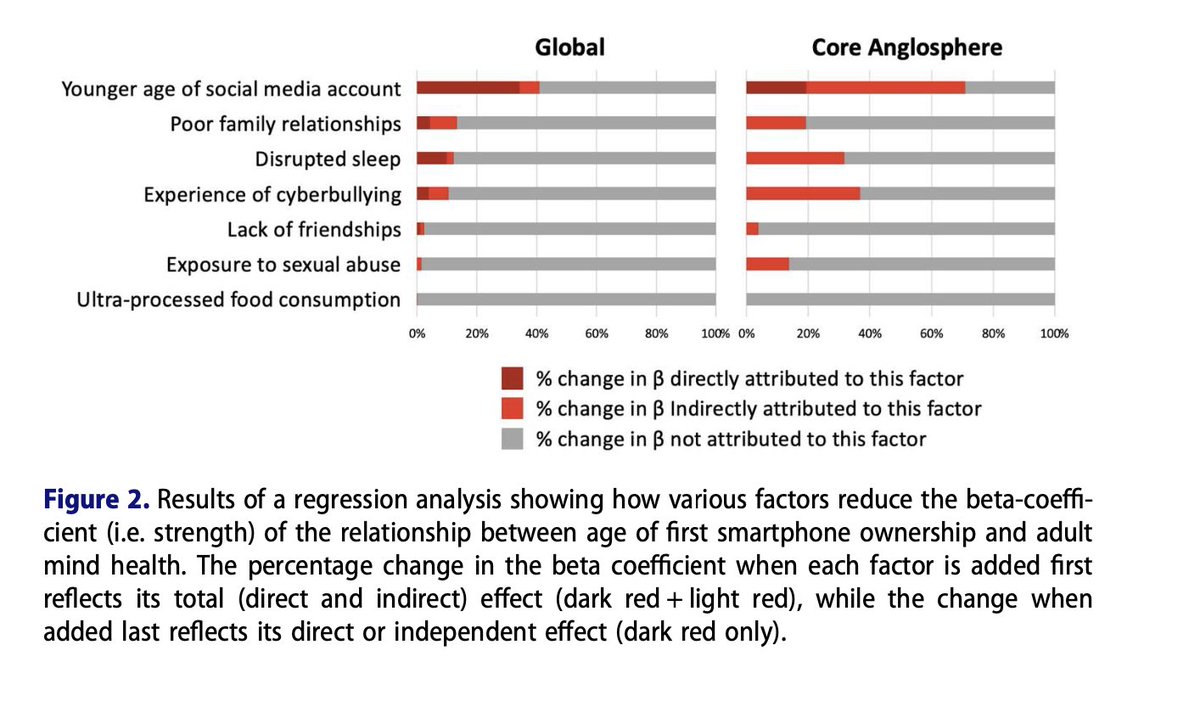

A new global study of over 100,000 young adults found that receiving a smartphone before age 13 is associated with significantly poorer mental health outcomes in early adulthood, particularly increased suicidal thoughts and diminished emotional regulation, with effects primarily mediated through early social media access.

A new global study of over 100,000 young adults found that receiving a smartphone before age 13 is associated with significantly poorer mental health outcomes in early adulthood, particularly increased suicidal thoughts and diminished emotional regulation, with effects primarily mediated through early social media access.

https://twitter.com/lennysan/status/1947810003169292371For whatever reason, the idea of knowing stuff has become unfashionable. We’ve absorbed the idea that facts are “mere” details, that skills and dispositions matter more, and that technology makes memory unnecessary.

The intervention was 10 minutes of students taking an unexpected, closed-notes practice test consisting of:

The intervention was 10 minutes of students taking an unexpected, closed-notes practice test consisting of:

What is interleaving and how does it work? Essentially it's really about a kind of discrimination: when learners encounter different items back-to-back, they must pay attention to what distinguishes one from the next. This strengthens their ability to categorise and apply the right rule or strategy.

What is interleaving and how does it work? Essentially it's really about a kind of discrimination: when learners encounter different items back-to-back, they must pay attention to what distinguishes one from the next. This strengthens their ability to categorise and apply the right rule or strategy.

9 out of 10 teachers still believe in the myth despite being thoroughly debunked by cognitive science. We've known this for 10 years. This to me is the most sobering aspect of all this and again, shows the pressing need for teachers to get proper training on how learning happens.

9 out of 10 teachers still believe in the myth despite being thoroughly debunked by cognitive science. We've known this for 10 years. This to me is the most sobering aspect of all this and again, shows the pressing need for teachers to get proper training on how learning happens.

I see a lot of training where school leaders use Ebbinghaus as a vehicle to talk about retrieval practice. While the basic premise is important, I don't think it's particularly useful for teachers because it's not really how learning happens in authentic learning situations.

I see a lot of training where school leaders use Ebbinghaus as a vehicle to talk about retrieval practice. While the basic premise is important, I don't think it's particularly useful for teachers because it's not really how learning happens in authentic learning situations.

Dominant motivation theories are valuable but underspecified. The paper acknowledges that current theories have "provided tremendous advancements in the understanding of motivation" and led to successful interventions, but argues they don't adequately explain how motivation actually works at a mechanistic level.

Dominant motivation theories are valuable but underspecified. The paper acknowledges that current theories have "provided tremendous advancements in the understanding of motivation" and led to successful interventions, but argues they don't adequately explain how motivation actually works at a mechanistic level.

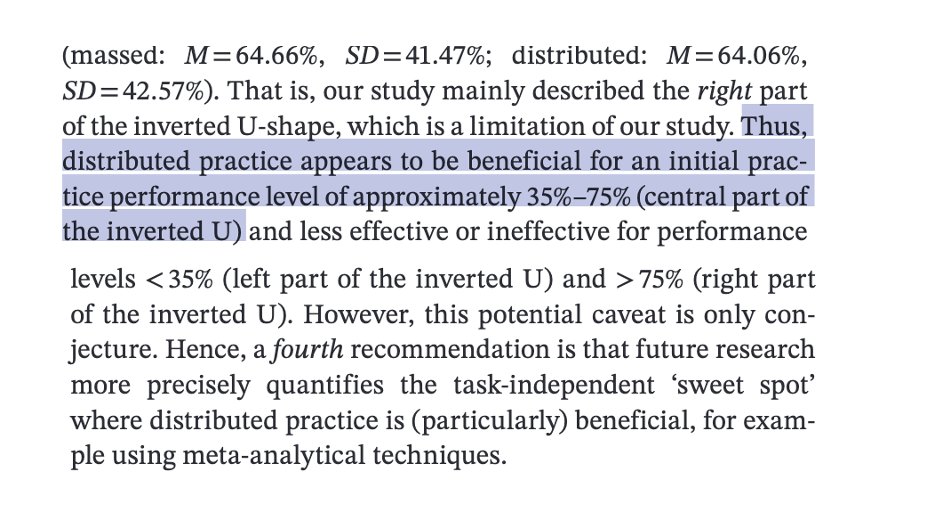

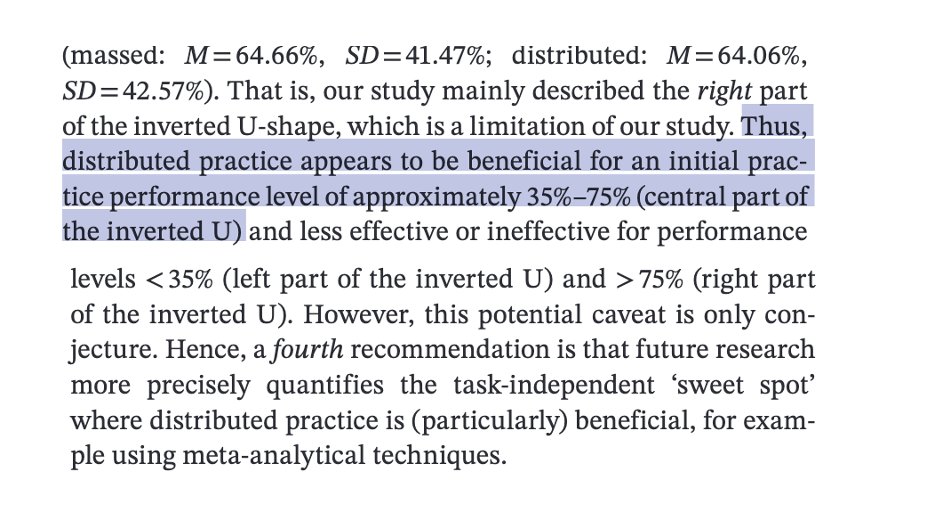

Specific evidence for this claim: "In Barzagar Nazari and Ebersbach's (2019a) study, the advantage of distributed practice occurred only for students scoring 3–7 out of 9.5 points, that is, 32%–74% on the first practice set. In Ebersbach and Barzagar Nazari's (2020a, Exp. 2) study, the advantage of distributed practice on transfer performance occurred only for students scoring >3.5 out of 9 points, that is, >39% on the first practice set." (p.12)

Specific evidence for this claim: "In Barzagar Nazari and Ebersbach's (2019a) study, the advantage of distributed practice occurred only for students scoring 3–7 out of 9.5 points, that is, 32%–74% on the first practice set. In Ebersbach and Barzagar Nazari's (2020a, Exp. 2) study, the advantage of distributed practice on transfer performance occurred only for students scoring >3.5 out of 9 points, that is, >39% on the first practice set." (p.12)

Been re-reading Theory of Instruction through a lens of what we know about learning from the last 50 years and really realising the brilliance of it in terms of how it incorporates so much of how learning happens. It's not an easy read but for me the core concept in it is "faultless communication": the idea that teaching should be designed so precisely that misunderstanding is impossible.

Been re-reading Theory of Instruction through a lens of what we know about learning from the last 50 years and really realising the brilliance of it in terms of how it incorporates so much of how learning happens. It's not an easy read but for me the core concept in it is "faultless communication": the idea that teaching should be designed so precisely that misunderstanding is impossible.

As you'd expect from Kalyuga, he argues that instructional strategies should incorporate CLT (cognitive load theory) to support biologically secondary learning (stuff kids learn in school), emphasizing worked examples, guided discovery, gradual reduction of scaffolds etc. but what's interesting is the idea that the "explicit intention to learn" is the driver behind humanity's cultural evolution and that intelligence is an emergent property of this.

As you'd expect from Kalyuga, he argues that instructional strategies should incorporate CLT (cognitive load theory) to support biologically secondary learning (stuff kids learn in school), emphasizing worked examples, guided discovery, gradual reduction of scaffolds etc. but what's interesting is the idea that the "explicit intention to learn" is the driver behind humanity's cultural evolution and that intelligence is an emergent property of this.

The paper basically argues that CLT is an outdated framework, rooted in 1980s cognitive psychology, and needs to be replaced by a richer, more holistic view of the brain and learning. Fair enough, let's see what they have to say... (Although I don't think the argument that just because something is old, it is 'outdated'. Indeed, the authors offer Darwin's theory of evolution as analogous to challenges to existing orthodoxies.)

The paper basically argues that CLT is an outdated framework, rooted in 1980s cognitive psychology, and needs to be replaced by a richer, more holistic view of the brain and learning. Fair enough, let's see what they have to say... (Although I don't think the argument that just because something is old, it is 'outdated'. Indeed, the authors offer Darwin's theory of evolution as analogous to challenges to existing orthodoxies.)

Essentially this paper advocates for a subtle but important distinction: instead of designing tasks based on the content or a static judgement of the learner, we should design tasks of dynamic difficulty based on the learner's relative expertise and the complexity of the material.

Essentially this paper advocates for a subtle but important distinction: instead of designing tasks based on the content or a static judgement of the learner, we should design tasks of dynamic difficulty based on the learner's relative expertise and the complexity of the material.

“The particular way that the human cognitive system works and the way that humans learn is due to the way their brains work. The way their brains work is due to biology. And our biology works the way it does because of evolution." Ok fair enough, nice initial rebuttal to the 'brain-as-computer' fallacy...

“The particular way that the human cognitive system works and the way that humans learn is due to the way their brains work. The way their brains work is due to biology. And our biology works the way it does because of evolution." Ok fair enough, nice initial rebuttal to the 'brain-as-computer' fallacy...