Do language models have an internal world model? A sense of time? At multiple spatiotemporal scales?

In a new paper with @tegmark we provide evidence that they do by finding a literal map of the world inside the activations of Llama-2!

In a new paper with @tegmark we provide evidence that they do by finding a literal map of the world inside the activations of Llama-2!

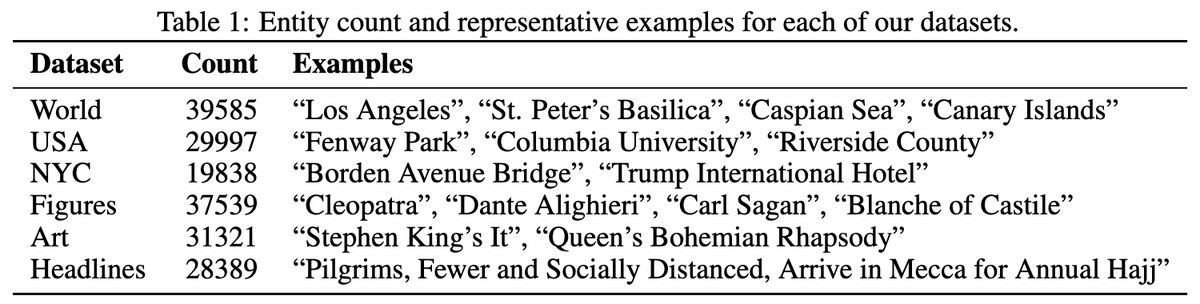

For spatial representations, we run Llama-2 models on the names of tens of thousands cities, structures, and natural landmarks around the world, the USA, and NYC. We then train linear probes on the last token activations to predict the real latitude and longitudes of each place.

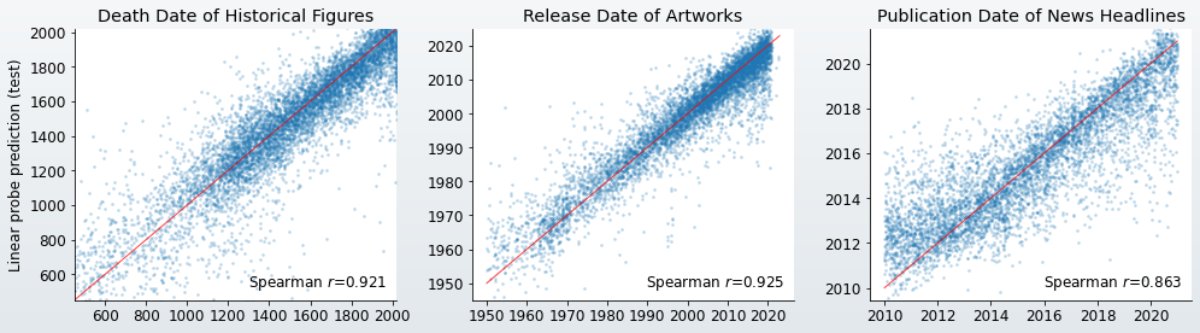

For temporal representations, we run the models on the names of famous figures from the past 3000 years, the names of songs, movies and books from 1950 onward, and NYT headlines from the 2010s and train lin probes to predict the year of death, release date, and publication date.

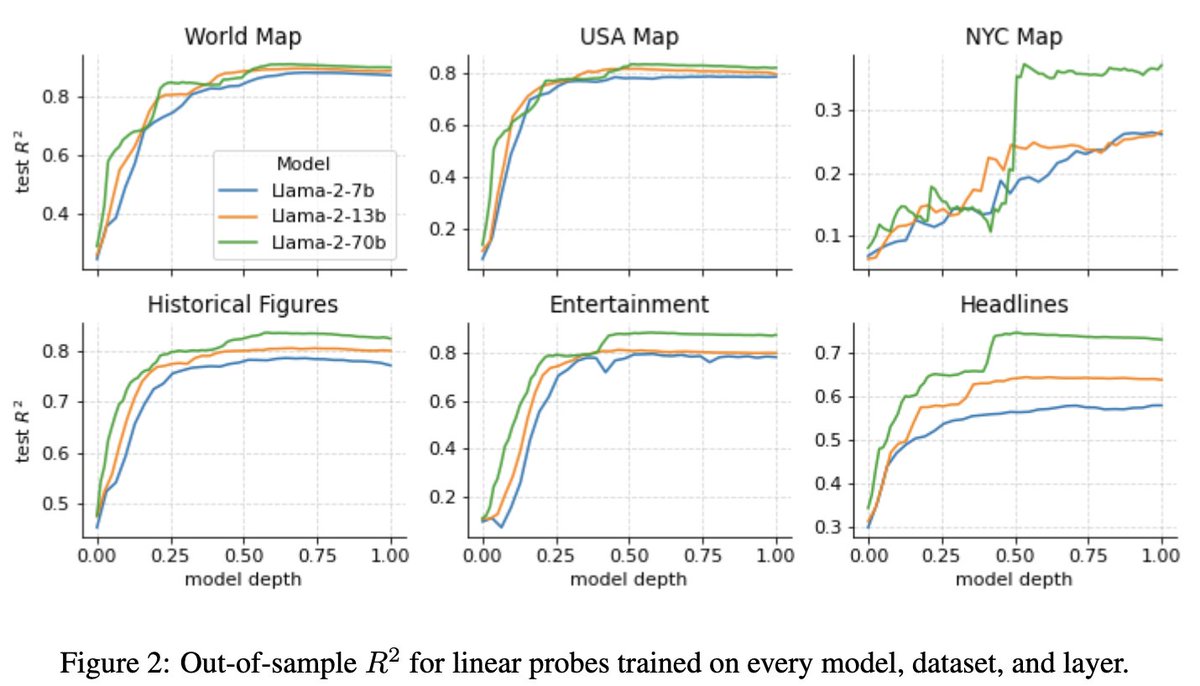

When training probes over every layer and model, we find that representations emerge gradually over the early layers before plateauing at around the halfway point. As expected, bigger models are better, but for more obscure datasets (NYC) no model is great.

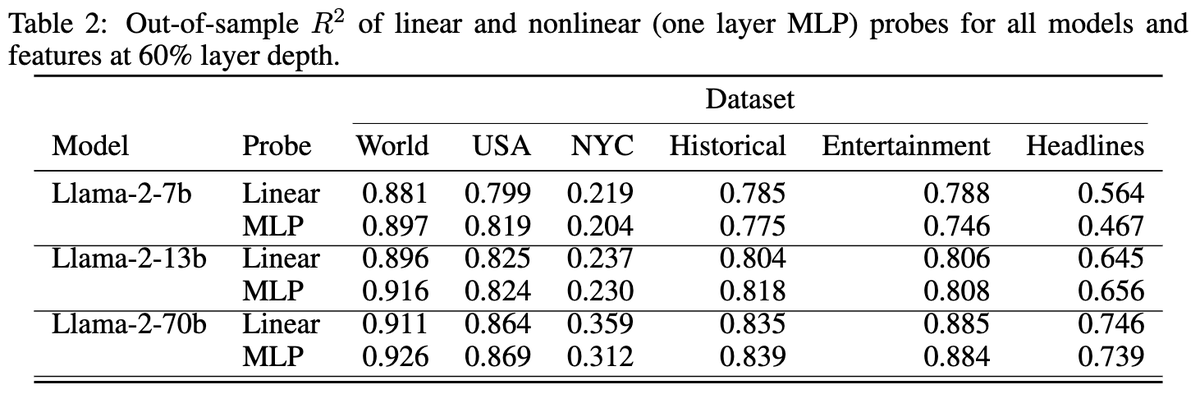

Are these representations actually linear? By comparing the performance of nonlinear MLP probes with linear probes, we find evidence that they are! More complicated probes do not perform any better on the test set.

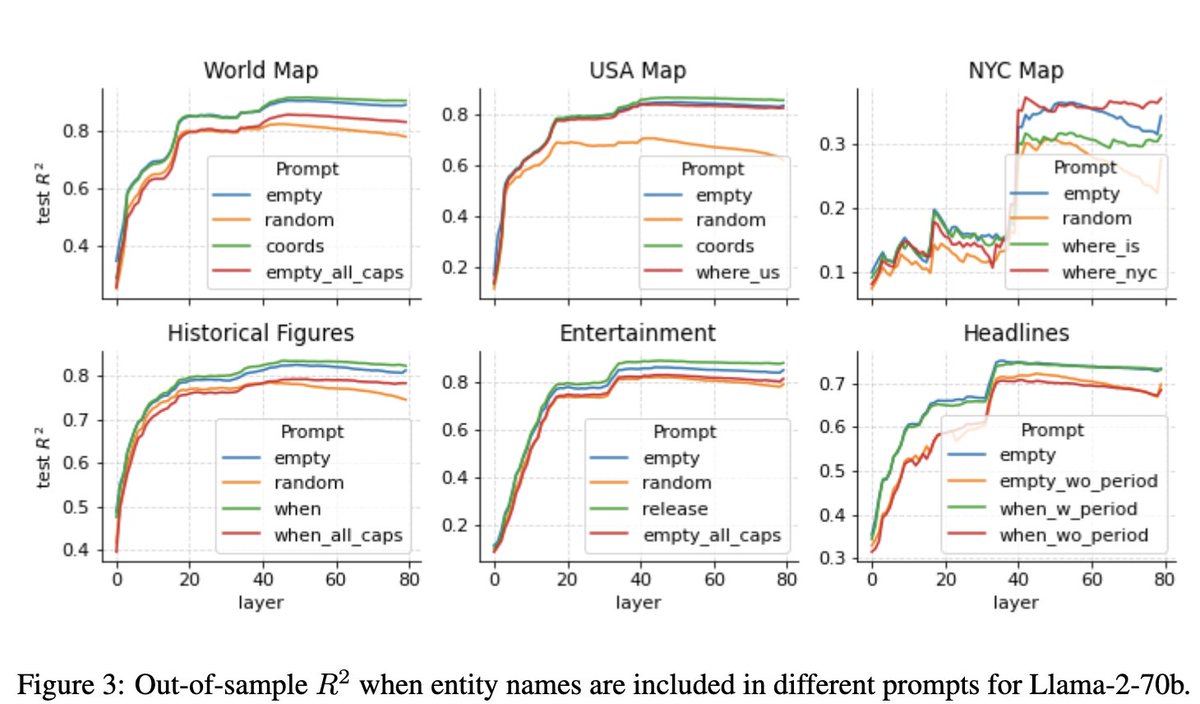

Are these representations robust to prompting? Probing on different prompts we find performance is largely preserved but can be degraded by capitalizing the entity name or prepending random tokens. Also probing on the trailing period instead of last token is better for headlines

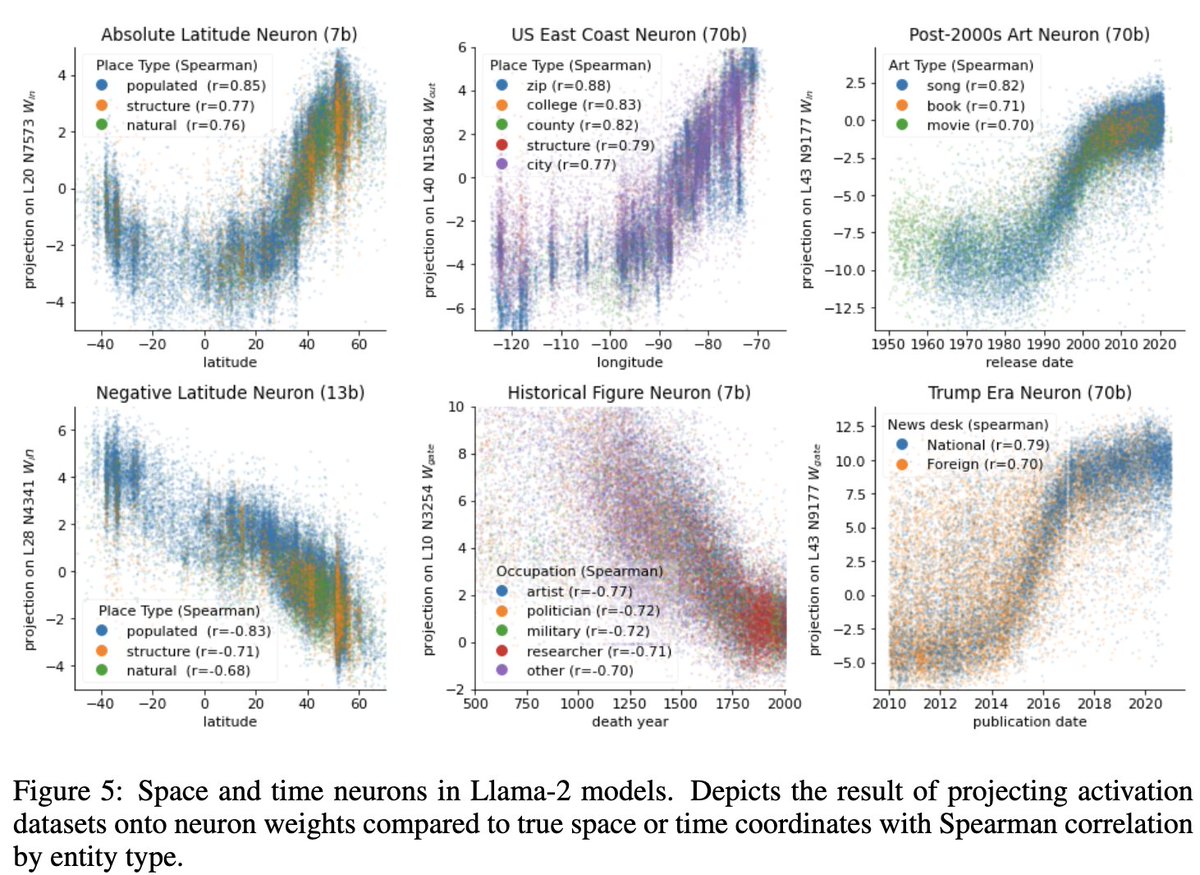

But does the model actually _use_ these representations? By looking for neurons with similar weights as the probe, we find many space and time neurons which are sensitive to the spacetime coords of an entity, showing the model actually learned the global geometry -- not the probe

A critical part of this project was constructing space and time datasets at multiple spatiotemporal scales with a diversity of entity types (eg, both cities and natural landmarks).

To see all the details and additional validations check out the

Paper:

Code and datasets: arxiv.org/abs/2310.02207

github.com/wesg52/world-m…

Paper:

Code and datasets: arxiv.org/abs/2310.02207

github.com/wesg52/world-m…

Finally, special shoutout to @NeelNanda5 for all the feedback on the paper and project!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh