In Autumn 1116 AD, a dying Alexios Komnenos marched East.

The Turks were once again encroaching on lands he had dedicated his life to returning to the Empire.

The last major battle the Byzantines had fought against the Turks was 45 years ago & 600 miles East; Manzikert.

The Turks were once again encroaching on lands he had dedicated his life to returning to the Empire.

The last major battle the Byzantines had fought against the Turks was 45 years ago & 600 miles East; Manzikert.

In the decade of chaos following the battle of Manzikert, Byzantine rule in Anatolia was swept aside as the imperial government convulsed in coups & rebellions. The largely demilitarized population of W. Anatolia surrendered as resistance continued in the better-prepared East.

Alexios Komnenos miraculously stabilized the government by orienting it around his influential & well-connected family. He refused to engage in blood feuds & forgave rebels after swiftly defeating them. Alexios knew he could make no new enemies nor waste any Byzantine men.

Most of Alexios’s early reign was a desperate struggle against the Normans & Pechenegs who threatened to overrun the Balkans. Through diplomatic maneuvering & tenacity Alexios managed to defeat both enemies by the early 1090s.

Alexios’s successes had allowed him to normalize the Empire’s financial & political situation as well as equip a small, professional army of mercenaries & native troops. However, many Byzantine elites were frustrated by Alexios’s lack of effort in recovering their Anatolian homes

To accomplish this Alexios asked for a small mercenary contingent from the Pope. The Pope took this opportunity to unite the squabbling warriors of Western Europe and point them East toward Jerusalem.

Alexios expertly managed this delicate situation & coordinated with these armies to recover much of Western Anatolia from the Turks. With the economic & demographic heartland of the empire recovered, Alexios could focus on more than just survival.

Despite this reconquest, the Turks remained in control of the interior of Anatolia, the steppe-like highlands perfectly suited to their nomadic lifestyle & mounted warfare. These Turks frequently raided Byzantine Anatolia, causing much destruction.

Alexios didn’t have the advantageous geography of his ancestors who used the high peaks of the Taurus Mountains to dampen Arab raids. The hills of Western Anatolia meant a more active defense was needed & Alexios’s armies frequently took the field to beat back Turkish raids.

In 1116 the border war had reached a fever pitch. Alexios, suffering severely from gout & asthma, marched out to thwart a large raid on NW Anatolia which he defeated at Poemanenum. As more & more raiders appeared in the area, Alexios made a bold move.

The emperor led his army into territory controlled by the Turks & turned southwards at Dorylaeum. He ravaged the region, hoping to create a no-man’s land. Alexios also deported the local Greek population to territories controlled by the Empire, a longstanding Byzantine policy.

As Alexios pressed deeper into the interior, swatting away Turkish resistance, the Sultan himself, Malik Shah, was forced to meet him on the field near Philomelion.

The army Malik met was not a rabble of conscripts or conglomerate of mercenary bands, but a disciplined & experienced force welded together by decades of campaigning. Alexios had taken great care to revive Byzantine arms & this generation had grown fierce under his guidance.

Alexios’s men took the field in a formation Alexios himself devised, the parataxis, a square of infantry with cavalry detachments behind & the baggage and Greek refugees in the center. This formation confused the Seljuks & their local commander, Manalugh, attacked hesitantly.

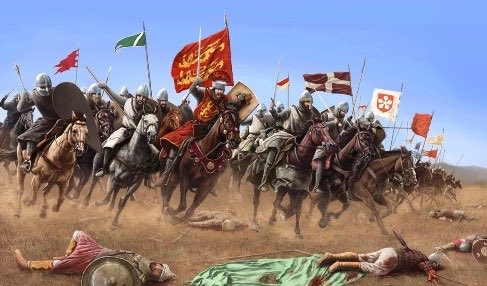

The following day Malik arrived with his army. He pressed the Byzantines aggressively at the front & rear of the parataxis. The Byzantine cavalry counterattacked & a charge under Nikephoros, Alexios’s son-in-law, broke the Turkish force led personally by Malik. The sultan fled.

After narrowly escaping capture, Malik led a night assault. Again, the Byzantine infantry held firm. The following day Malik surrounded the Byzantines & attacked on all sides. His frenetic attacks came to nothing & waves of horse archers broke on the rock of Alexios’s infantry.

Unlike Manzikert where the Byzantines marched haphazardly across the plains in pursuit of the Seljuks, the army took no bait & the cavalry showed great discipline in conducting calculated & limited counter-charges.

Alexios knew the sultan would have to fight & try to eject him from Seljuk lands or else risk losing legitimacy & so adopted a static formation impervious to Turkish strengths.

Malik, unable to dislodge Alexios & suffering casualties in his attempts, sued for peace. Alexios greeted the Sultan warmly, draping him in his own cloak. The Sultan was make every effort to stop Turkish raiding parties on Byzantines & accept a level of subordination to Alexios.

Alexios’s ability to match with impunity through Turkish territory & the iron discipline of his men proved a watershed moment. Byzantine arms were once again dominant in Anatolia, the Turks could be beaten.

The loss of prestige Malik suffered in his surrender led to his deposition & murder by his brother in 1118, the same year Alexios died & left his dream of restoration to his capable son, John.

Alexios’s parataxis formation bears remarkable similarity to the formation Nikephoros Phokas described in the Praecepta Militaria, which he used to great effect against the Hamdanids. Alexios must’ve reconstructed the Byzantine military with Nikephoros’s teachings in mind.

This formation outgrew even Byzantine military theory & Richard Lionheart’s formation during his great victory at Asruf bears surprising similarity to that of these brilliant Byzantine Emperors.

It’s possible crusaders learned these tactics from the Byzantines or by their own experience against the same warriors the Byzantines perfected this strategy against. Some similarity can even be drawn with Tercios & Napoleonic Infantry squares; both under similar pressures.

Alexios’s final battle demonstrated the miracle he had given Byzantium. Where he found a squabbling & dying Empire with hardly a few regiments to call, he left a unified & prosperous one with a capable & disciplined army & an equally capable heir to lead them to greater heights.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh