1 of 3/ The ongoing assault against Western history, epitomized by the decades-long systematic denigration of the Crusades and the Crusaders, is a key component of the greater war being waged against Western civilization and identity, with the ultimate goal being White erasure.

The first step towards ethnocultural erasure is the destruction of the past. Rewrite the past, control the future. A people without a past have no future.

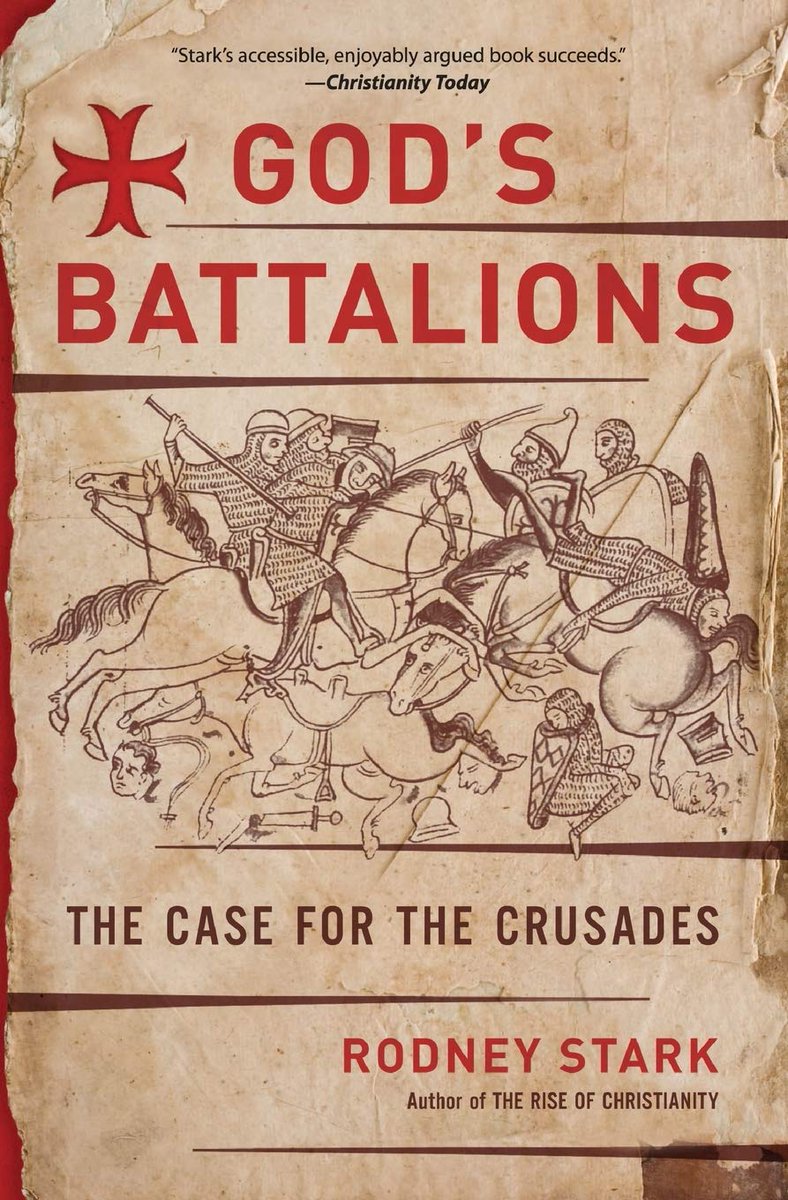

With the above in mind, let's briefly examine the Crusades, their true origins, and the men who participated in this noble endeavor. I will be drawing extensively from Rodney Stark's excellent book, "God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades."

The first step towards ethnocultural erasure is the destruction of the past. Rewrite the past, control the future. A people without a past have no future.

With the above in mind, let's briefly examine the Crusades, their true origins, and the men who participated in this noble endeavor. I will be drawing extensively from Rodney Stark's excellent book, "God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades."

2 of 3/ Contrary to popular Western historiography (how we write and portray history), the Crusades were not the imperialistic undertakings of "White aggressors," nor were they an early form of European colonialism.

In fact, they were largely defensive wars, precipitated by Islamic provocations, and centuries of bloody attempts to expand into the West, coupled by merciless attacks on Christian pilgrims and holy sites.

Rodney Stark, in his book "God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades," sums up the reality of the dire geopolitical situation faced by Europe quite succinctly, writing:

"The Crusades were not unprovoked. They were not the first round of European colonialism. They were not conducted for land, loot, or converts. The crusaders were not barbarians who victimized the cultivated Muslims."

In short, the Crusades only began after more than 300 years of non-stop Muslim aggression against the Christian world.

It's important to note that while the most well-known Crusades to the Holy Land occurred from 1095 to 1291 AD, the broader Crusading period extended from 1095 to 1492 AD. This period encompasses the entirety of the Reconquista and various other related military campaigns, illustrating that the Crusades were part of a larger series of defensive wars waged to halt Islamic expansion.

The Reconquista, culminating in 1492 AD with the fall of Granada, marked the end of a 700-year struggle for the liberation of the Iberian Peninsula, which began with the Muslim Moors' conquest of the Visigothic Christian kingdoms in 711 AD.

Additionally, Islamic expansion into Europe did not cease in 1492 AD; it continued until the failed Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683 AD.

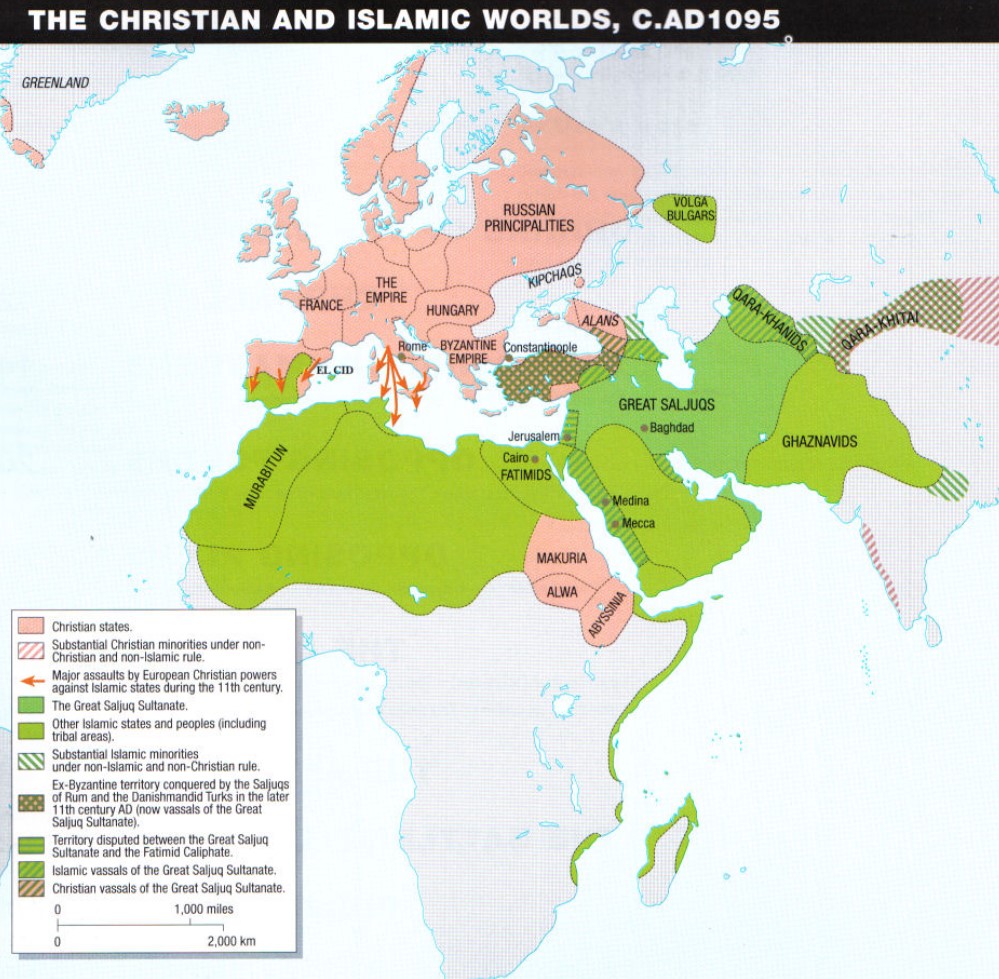

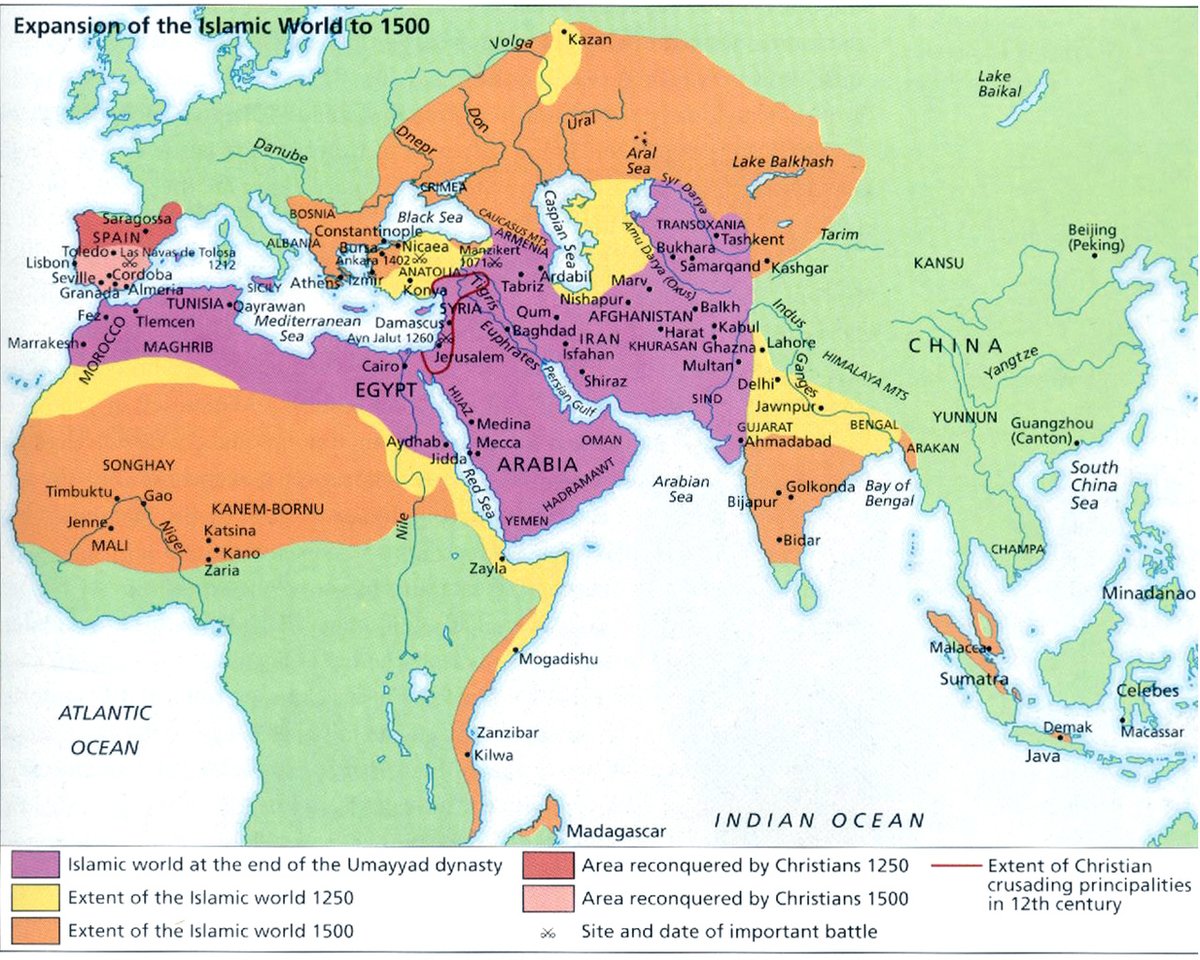

Two maps are presented below, one from 1095 AD, the year the First Crusade was launched, and one from circa 1500 AD, showing the massive expansion of Islam from Europe to Asia.

In fact, they were largely defensive wars, precipitated by Islamic provocations, and centuries of bloody attempts to expand into the West, coupled by merciless attacks on Christian pilgrims and holy sites.

Rodney Stark, in his book "God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades," sums up the reality of the dire geopolitical situation faced by Europe quite succinctly, writing:

"The Crusades were not unprovoked. They were not the first round of European colonialism. They were not conducted for land, loot, or converts. The crusaders were not barbarians who victimized the cultivated Muslims."

In short, the Crusades only began after more than 300 years of non-stop Muslim aggression against the Christian world.

It's important to note that while the most well-known Crusades to the Holy Land occurred from 1095 to 1291 AD, the broader Crusading period extended from 1095 to 1492 AD. This period encompasses the entirety of the Reconquista and various other related military campaigns, illustrating that the Crusades were part of a larger series of defensive wars waged to halt Islamic expansion.

The Reconquista, culminating in 1492 AD with the fall of Granada, marked the end of a 700-year struggle for the liberation of the Iberian Peninsula, which began with the Muslim Moors' conquest of the Visigothic Christian kingdoms in 711 AD.

Additionally, Islamic expansion into Europe did not cease in 1492 AD; it continued until the failed Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683 AD.

Two maps are presented below, one from 1095 AD, the year the First Crusade was launched, and one from circa 1500 AD, showing the massive expansion of Islam from Europe to Asia.

3 of 3/ As previously mentioned, most liberal historical narratives often inaccurately depict the Crusades as unprovoked acts of aggression and a precursor to European colonialism. They commonly assert that these campaigns were led by the so-called "surplus sons" of avaricious European nobles, motivated by a combination of bloodlust and the desire for material wealth.

Contrary to the typical depiction of "surplus sons" seeking the spoils of war, Stark describes the Crusaders as "the heads of great families who were fully aware that the costs of crusading would far exceed the very modest material rewards that could be expected; most went at immense personal cost, some of them knowingly bankrupting themselves to go."

For instance, in contrast to the Second (1147-1149 AD) and Third Crusades (1189–1192 AD), the First Crusade (1096-1099 AD) was chiefly led by European noble families, rather than royalty, and was undertaken more for piety than greed.

As the eldest son of Pons, Count of Toulouse, and Almodis de La Marche, Raymond IV inherited not only his father's title but also the weighty responsibilities that came with his noble lineage. He was a pivotal figure in the First Crusade, renowned for his exceptional bravery as a knight and his deep religious devotion. This profound spiritual commitment was so fervent that he expressed a desire to be buried in the Holy Land, which ultimately motivated his participation in the Crusade.

Furthermore, Stark emphasizes a crucial, often overlooked aspect of the Crusades, stating, "Crusading was dominated by a few closely related families! It appears that it was not so much that individuals decided to accept the Pope’s summons, but that entire families did."

This highlights that the decision to participate in the Crusades was often a communal response deeply rooted in faith. Unlike the common portrayal of these endeavors as driven by a thirst for blood and greed, Stark's observation suggests that for many, the motivation was a collective spiritual calling, with families uniting in their commitment to what in essence was a holy cause.

Stark provides a compelling example to illustrate this faith-driven family commitment to the Crusades. He uses the case of Count William Tête-Hardi of Burgundy and writes: "He had five sons. Of these, three went on the First Crusade, and the fourth became a priest who, as Pope Calixtus II (1119-1124), inaugurated an extension of the Crusade to attack Damascus in 1122. Count William also had four daughters. Three were married to men who joined their brothers-in-law and went on the First Crusade, and the fourth was the mother of a First Crusader. As for the Second Crusade, this family sent ten crusaders in 1147."

In short, Crusading was essentially a family endeavor, where entire households committed themselves to this noble cause, frequently at great personal sacrifice.

Far from being a profitable venture, Crusading was a tremendously costly undertaking. The commanders of the Crusader armies shouldered the bulk of these expenses, covering everything from provisioning the soldiers, outfitting them with armor and weapons, to handling logistics and arranging transportation, whether by sea or overland.

Meeting the financial demands of the Crusades often led many leaders to the brink of financial ruin. It wasn't just the heads of great noble houses who bore the costs; individual knights also faced significant expenses.

Stark elaborates: "Crusading was a very expensive undertaking. A knight needed armor, arms, at least one warhorse (preferably two or three), a palfrey (a riding horse), and packhorses or mules, all of them being very costly items. For example, Guy of Thiers paid ten pounds for a warhorse, which was equal to more than two years of salary for a ship's captain. A knight also needed servants (one or two to take care of the horses), clothing, tenting, an array of supplies such as horseshoes, and a substantial amount of cash to buy supplies along the way, in addition to those supplies that could be looted or were contributed, and he needed to pay various members of his entourage."

In essence, the Crusaders were not driven by greed, but were often deeply pious men. As Stark wrote, they "...truly believed that they served in God’s battalions." This reflects their profound commitment to religious duty in service to greater Christendom, rather than the satiation of base materialistic desires.

Stark highlights the severe economic challenges faced by the Crusader states, collectively known as the Outremer (French for "Overseas"). These included the County of Edessa (1098–1150), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the County of Tripoli (1102–1289), and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291).

Stark emphasizes that "the Crusader kingdoms established in the Holy Land, which endured for nearly two centuries, were not self-sustaining colonies reliant on local exactions. Instead, they necessitated substantial subsidies from Europe."

This indicates that the survival of these kingdoms relied heavily on support from various European populations, the Catholic Church, European nobility, and royal generosity. This support was driven not only by Europe's deep faith but also as a response to the very real threat of a militarily expansive Islam. Therefore, Crusading was not a financially profitable venture, but rather one primarily motivated by a desire to serve God, protect Christendom, and preserve European religious and cultural integrity against Islamic aggression.

In sum, the Crusades were not wars of aggression foreshadowing later European colonial endeavors; instead, they were fundamentally defensive campaigns against an advancing militaristic Islam. The Crusaders, far from being mere seekers of wealth or driven by bloodlust, were primarily motivated by deep religious convictions and a collective commitment to the defense and preservation of Christendom.

Contrary to the typical depiction of "surplus sons" seeking the spoils of war, Stark describes the Crusaders as "the heads of great families who were fully aware that the costs of crusading would far exceed the very modest material rewards that could be expected; most went at immense personal cost, some of them knowingly bankrupting themselves to go."

For instance, in contrast to the Second (1147-1149 AD) and Third Crusades (1189–1192 AD), the First Crusade (1096-1099 AD) was chiefly led by European noble families, rather than royalty, and was undertaken more for piety than greed.

As the eldest son of Pons, Count of Toulouse, and Almodis de La Marche, Raymond IV inherited not only his father's title but also the weighty responsibilities that came with his noble lineage. He was a pivotal figure in the First Crusade, renowned for his exceptional bravery as a knight and his deep religious devotion. This profound spiritual commitment was so fervent that he expressed a desire to be buried in the Holy Land, which ultimately motivated his participation in the Crusade.

Furthermore, Stark emphasizes a crucial, often overlooked aspect of the Crusades, stating, "Crusading was dominated by a few closely related families! It appears that it was not so much that individuals decided to accept the Pope’s summons, but that entire families did."

This highlights that the decision to participate in the Crusades was often a communal response deeply rooted in faith. Unlike the common portrayal of these endeavors as driven by a thirst for blood and greed, Stark's observation suggests that for many, the motivation was a collective spiritual calling, with families uniting in their commitment to what in essence was a holy cause.

Stark provides a compelling example to illustrate this faith-driven family commitment to the Crusades. He uses the case of Count William Tête-Hardi of Burgundy and writes: "He had five sons. Of these, three went on the First Crusade, and the fourth became a priest who, as Pope Calixtus II (1119-1124), inaugurated an extension of the Crusade to attack Damascus in 1122. Count William also had four daughters. Three were married to men who joined their brothers-in-law and went on the First Crusade, and the fourth was the mother of a First Crusader. As for the Second Crusade, this family sent ten crusaders in 1147."

In short, Crusading was essentially a family endeavor, where entire households committed themselves to this noble cause, frequently at great personal sacrifice.

Far from being a profitable venture, Crusading was a tremendously costly undertaking. The commanders of the Crusader armies shouldered the bulk of these expenses, covering everything from provisioning the soldiers, outfitting them with armor and weapons, to handling logistics and arranging transportation, whether by sea or overland.

Meeting the financial demands of the Crusades often led many leaders to the brink of financial ruin. It wasn't just the heads of great noble houses who bore the costs; individual knights also faced significant expenses.

Stark elaborates: "Crusading was a very expensive undertaking. A knight needed armor, arms, at least one warhorse (preferably two or three), a palfrey (a riding horse), and packhorses or mules, all of them being very costly items. For example, Guy of Thiers paid ten pounds for a warhorse, which was equal to more than two years of salary for a ship's captain. A knight also needed servants (one or two to take care of the horses), clothing, tenting, an array of supplies such as horseshoes, and a substantial amount of cash to buy supplies along the way, in addition to those supplies that could be looted or were contributed, and he needed to pay various members of his entourage."

In essence, the Crusaders were not driven by greed, but were often deeply pious men. As Stark wrote, they "...truly believed that they served in God’s battalions." This reflects their profound commitment to religious duty in service to greater Christendom, rather than the satiation of base materialistic desires.

Stark highlights the severe economic challenges faced by the Crusader states, collectively known as the Outremer (French for "Overseas"). These included the County of Edessa (1098–1150), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the County of Tripoli (1102–1289), and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291).

Stark emphasizes that "the Crusader kingdoms established in the Holy Land, which endured for nearly two centuries, were not self-sustaining colonies reliant on local exactions. Instead, they necessitated substantial subsidies from Europe."

This indicates that the survival of these kingdoms relied heavily on support from various European populations, the Catholic Church, European nobility, and royal generosity. This support was driven not only by Europe's deep faith but also as a response to the very real threat of a militarily expansive Islam. Therefore, Crusading was not a financially profitable venture, but rather one primarily motivated by a desire to serve God, protect Christendom, and preserve European religious and cultural integrity against Islamic aggression.

In sum, the Crusades were not wars of aggression foreshadowing later European colonial endeavors; instead, they were fundamentally defensive campaigns against an advancing militaristic Islam. The Crusaders, far from being mere seekers of wealth or driven by bloodlust, were primarily motivated by deep religious convictions and a collective commitment to the defense and preservation of Christendom.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter