One of the most amazing feats of military engineering in the Middle Ages was the galeas per montes (galleys across mountains)!

In 1438-39, the Republic of Venice transported a large number of ships from the Adriatic Sea to Lake Garda.

This included a difficult land journey. 🧵

In 1438-39, the Republic of Venice transported a large number of ships from the Adriatic Sea to Lake Garda.

This included a difficult land journey. 🧵

This happened in the context of Wars in Lombardy, a series of conflicts between large coalitions of Italian cities led by the Duchy of Milan and Republic of Venice, as these two rival powers clashed in northern Italy.

The war lasted 1423 to 1454.

The war lasted 1423 to 1454.

The Venetians had long been a formidable sea power.

But in 15th century they started to also rapidly expand their Domini di Terraferma (mainland domains).

On this map you can see the territories gained by Venetians, and the year in which they came into their possession.

But in 15th century they started to also rapidly expand their Domini di Terraferma (mainland domains).

On this map you can see the territories gained by Venetians, and the year in which they came into their possession.

The Venetians were successful in this expansion, for the regions of northern Italy are crossed by many waterways.

This allowed the Venetians to make use of their naval technology, using powerful river fleets which allowed them to transport men and equipment quickly.

This allowed the Venetians to make use of their naval technology, using powerful river fleets which allowed them to transport men and equipment quickly.

But by 1438, the Duke of Milan Filippo Maria Visconti was able to push the Venetians back and took control of southern shores of Lake Garda.

That same year the Milanese mercenary army led by Niccolò Piccinino began besieging the Venetian-controlled city of Brescia.

That same year the Milanese mercenary army led by Niccolò Piccinino began besieging the Venetian-controlled city of Brescia.

The only way the Venetians could reach Brescia would be through Lake Garda.

They decided to send their powerful Mediterranean warships to Lake Garda!

But the Milanese controlled the southern part of the lake where the Mincio river connects it to the Adriatic sea.

They decided to send their powerful Mediterranean warships to Lake Garda!

But the Milanese controlled the southern part of the lake where the Mincio river connects it to the Adriatic sea.

This meant that the only way to get Venetian ships to Lake Garda was to transport them on Adige river (marked on this map with light blue color) and then partially by land through the mountains (the path in red color) to the safe port of Torbole in the north of Lake Garda.

This 20km land journey would include passing the Loppio Lake and the narrow Pass of San Giovanni.

But Venetian engineers Blasio de Arboribus, Niccolò Carcavilla, and Niccolò Sorbolo, who proposed this ambitious plan to the Venetian Senate, were confident that this was possible!

But Venetian engineers Blasio de Arboribus, Niccolò Carcavilla, and Niccolò Sorbolo, who proposed this ambitious plan to the Venetian Senate, were confident that this was possible!

The plan was accepted and the expedition started in December 1438, when 30 Venetian vessels entered the mouths of the Adige river near Sottomarina.

The fleet went upstream to Verona and then to the village of Rovereto, where it was beached.

The fleet went upstream to Verona and then to the village of Rovereto, where it was beached.

Now began the final and most difficult part of the journey: the transport of ships from Rovereto to Torbole on land.

But the Venetians were well prepared.

An army of engineers and workers, as well as 2000 oxen, were ready to transport warships over the difficult terrain.

But the Venetians were well prepared.

An army of engineers and workers, as well as 2000 oxen, were ready to transport warships over the difficult terrain.

The route from the Adige river to the Loppio lake was hard.

The Venetians designed and built special devices for the operations, and hired hundreds of workers including diggers, carpenters, sailors, and local craftsmen!

After immense effort of men they reached the Loppio lake.

The Venetians designed and built special devices for the operations, and hired hundreds of workers including diggers, carpenters, sailors, and local craftsmen!

After immense effort of men they reached the Loppio lake.

The Loppio lake made the journey a bit easier since the ships could sail over the lake.

The lake basin is now a wetland since the construction of the Mori-Torbole Tunnel in 1954.

The picture on the left from 19th century shows how it looked like prior to that.

The lake basin is now a wetland since the construction of the Mori-Torbole Tunnel in 1954.

The picture on the left from 19th century shows how it looked like prior to that.

After they passed the Loppio lake, the difficult journey continued.

The workers flattened the road that would be used by the fleet. They leveled natural and man-made obstacles, and built several bridges.

The largest galleys required more than 200 oxen to be dragged!

The workers flattened the road that would be used by the fleet. They leveled natural and man-made obstacles, and built several bridges.

The largest galleys required more than 200 oxen to be dragged!

The descent from the San Giovanni Pass to Torbole was very dangerous, for the ships could potentially crash against rocks.

To slow down the ships they tied large boulders to their masts and unfurled the sails.

To slow down the ships they tied large boulders to their masts and unfurled the sails.

The entire operation lasted over three months and cost the Republic a staggering 15,000 ducats!

It took incredible effort but eventually the Venetian ships finally reached Torbole in April 1439.

It was a victory of technology and sheer human will.

It took incredible effort but eventually the Venetian ships finally reached Torbole in April 1439.

It was a victory of technology and sheer human will.

What a sight it must have been seeing the marvelous Venetian navy finally sailing in the Lake Garda, flying the illustrious standards of St. Mark!

This miraculous achievement greatly increased the prestige of Venice.

Nothing was impossible for the mighty La Serenissima.

This miraculous achievement greatly increased the prestige of Venice.

Nothing was impossible for the mighty La Serenissima.

The Venetian fleet was able to resupply the besieged city of Brescia.

But the troubles were not over yet.

The Milanese quickly reacted to Venetian presence in the lake and defeated the Venetians in two naval battles on 12 April and 26 September 1439.

But the troubles were not over yet.

The Milanese quickly reacted to Venetian presence in the lake and defeated the Venetians in two naval battles on 12 April and 26 September 1439.

The Venetians were forced to take refuge in the port of Torbole were they repaired their damaged ships.

The next year they decisively defeated the Milanese navy near the Ponale pass.

These waters turned red with blood as the Venetians asserted their control over the lake.

The next year they decisively defeated the Milanese navy near the Ponale pass.

These waters turned red with blood as the Venetians asserted their control over the lake.

This painting by Tintoretto depicts the glorious Venetian victory at Lake Garda.

It is placed on the ceiling of the Hall of the Great Council in the Doge's Palace in Venice, reminding of the epic undertaking of galeas per montes.

It is placed on the ceiling of the Hall of the Great Council in the Doge's Palace in Venice, reminding of the epic undertaking of galeas per montes.

The Venetians used their control of the lake to capture the castle of Salò, which was important for defense of the territory of Brescia.

They were then able to finally relieve the siege of Brescia and retained their control over the city.

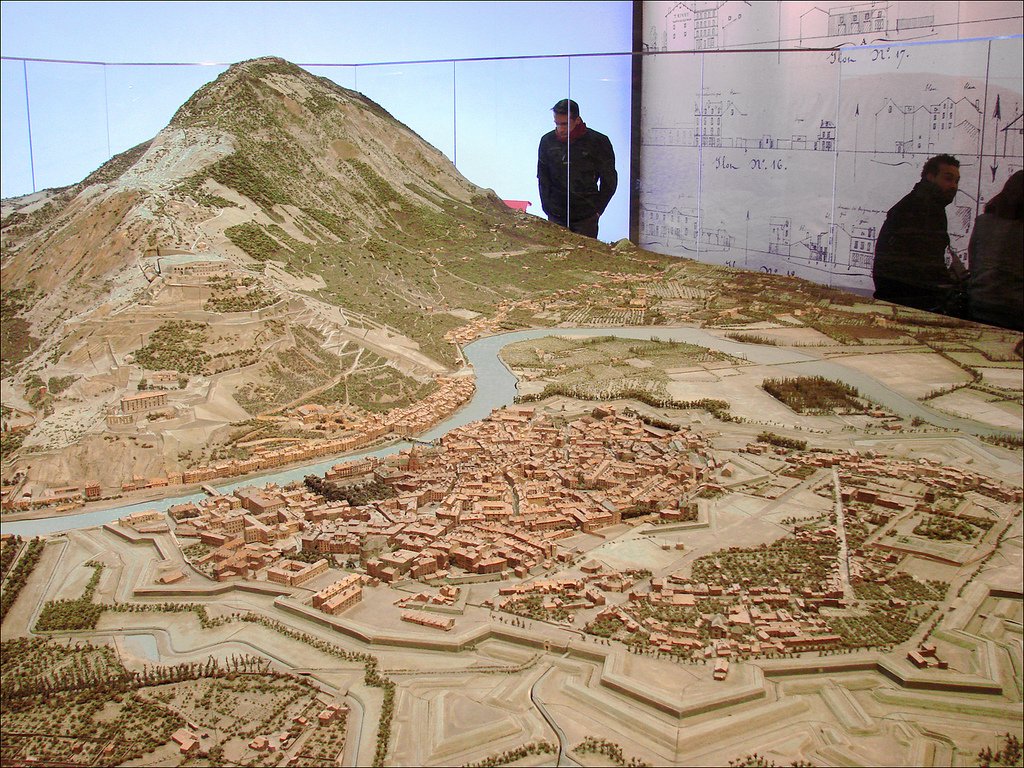

A reconstruction of medieval Brescia:

They were then able to finally relieve the siege of Brescia and retained their control over the city.

A reconstruction of medieval Brescia:

The glorious feat of galeas per montes was also recorded in a map called the Almagià map, made in 1440.

It depicts the entire journey from the Adriatic Sea to Lake Garda.

It depicts the entire journey from the Adriatic Sea to Lake Garda.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh