On the sixtieth anniversary of John F. Kennedy's assassination, here's a thread on his relationship with Nikita Khrushchev, one of the most important relationships of the Cold War.

Moscow welcomed JFK's election as President in 1960. Khrushchev's relationship with Eisenhower deteriorated sharply after the U2 incident in May 1960. He privately called Ike a "non-entity", and derided Vice President Nixon, as a "careerist," a "time-server", and "an empty suit."

The young and untried Kennedy was therefore a welcome change, and Khrushchev would later claim that he had "voted" for him by agreeing to release detained US airmen from the downed reconnaissance plane RB-47H.

Khrushchev expected to do business with Kennedy. What he really wanted was to reach an agreement on Berlin, which the Soviet leader called a "rotten tooth". But when the two met at a summit in Vienna in June 1961, Khrushchev discovered that Kennedy was unbending on the issue.

BTW there is a widespread view in the historiography that Khrushchev managed to intimidate the inexperienced Kennedy at the Vienna summit. It is an erroneous view in my opinion. Kennedy stood his ground, and Khrushchev's bullying tactics got him nowhere.

But Khrushchev did have this very peculiar view of Kennedy as being manipulatable by what is today sometimes called the "deep state," but which for Khrushchev entailed some combination of the military brass and the American oligarchy.

He worried about this, because he thought that these shady manipulators would press Kennedy into starting a war that the young President wanted to avoid, etc.

This view of Khrushchev's (completely baseless btw) was consequential in his decision-making in Berlin (he decided against pushing JFK into the corner, and ultimately ordered to build the Berlin Wall in August 1961, which helped diffuse the crisis in the medium-term).

Then came the Cuban Missile Crisis. Khrushchev and Kennedy were somehow able to feel each other out, and to find the common ground, which allowed them to step back from the brink. You know what I find striking in their interaction in October 1962?

It wasn't Kennedy's toughness (oversold), nor Khrushchev's combativeness (he was in fact a lot less combative than we tend to assume). It was their shared experience of war (both were of course WWII veterans), and their absolute determination to avoid a repetition.

I worry that today's leaders, lacking this direct experience of a major war, are rather less cautious. I am thinking of Putin's comments last year (on the anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis) that he was no Nikita Khrushchev. True. And that's worrying.

Anyway, the shared experience "on the brink" brought Khrushchev and Kennedy closer. What followed was a period of improving relations, a mini-detente, sadly cut short by Kennedy's assassination in 1963 and Khrushchev's overthrow in 1964.

Khrushchev was deeply saddened by the assassination (contrary to conspiracy theories, he had nothing at all to do with it). On Nov. 23 he visited the US Embassy in Moscow where, in a conversation with Ambassador Foy D. Kohler, he praised JFK's "tact," "realism" and "knowledge."

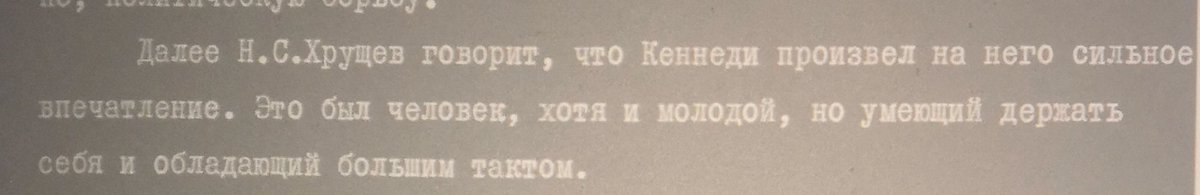

Here are some snippets from this conversation, from the Russian archives (never published before): "N.S. Khrushchev says that Kennedy made a strong impression on him. This was a man, who, although he was young, knew how to handle himself."

And then: "N.S. Khrushchev says that Kennedy had one important trait: a feeling for reality, which cannot be learned through any diplomatic science."

A lot more on the Kennedy-Khrushchev relationship in my forthcoming book, To Run the World, which you can pre-order here: . Use the code TRTW20 to receive 20% off your order. cambridge.org/it/universityp…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter