I spend a lot of time analyzing and documenting outlier SARS-CoV-2 sequences. Recently, I’ve noticed a fascinating pattern: the repeated appearance of paired mutations in two narrow NSP12 regions >2400 nucleotides distant from each other. 1/45

NSP12 is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), part of the SARS-CoV-2 replication complex, which also includes NSP7-10 and NSP13-14. I discussed some basics of the RdRp & coronavirus genome replication previously. 2/45

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1673488103313424385

The first two-thirds of the SARS-CoV-2 genome consists of ORF1a & ORF1b. When the full genome enters a ribosome, the cell protein-making machine, only ORF1a is translated ~75% of the time. The ribosome hits a stop codon & cuts loose. No ORF1b. 3/45

But the other ~25% of the time, at the end of ORF1a, the ribosome gets tangled in a complex RNA structure called a pseudoknot. They say the ribosome “slips,” but to me it seems more like it gets stuck & momentarily stumbles backward. 4/45

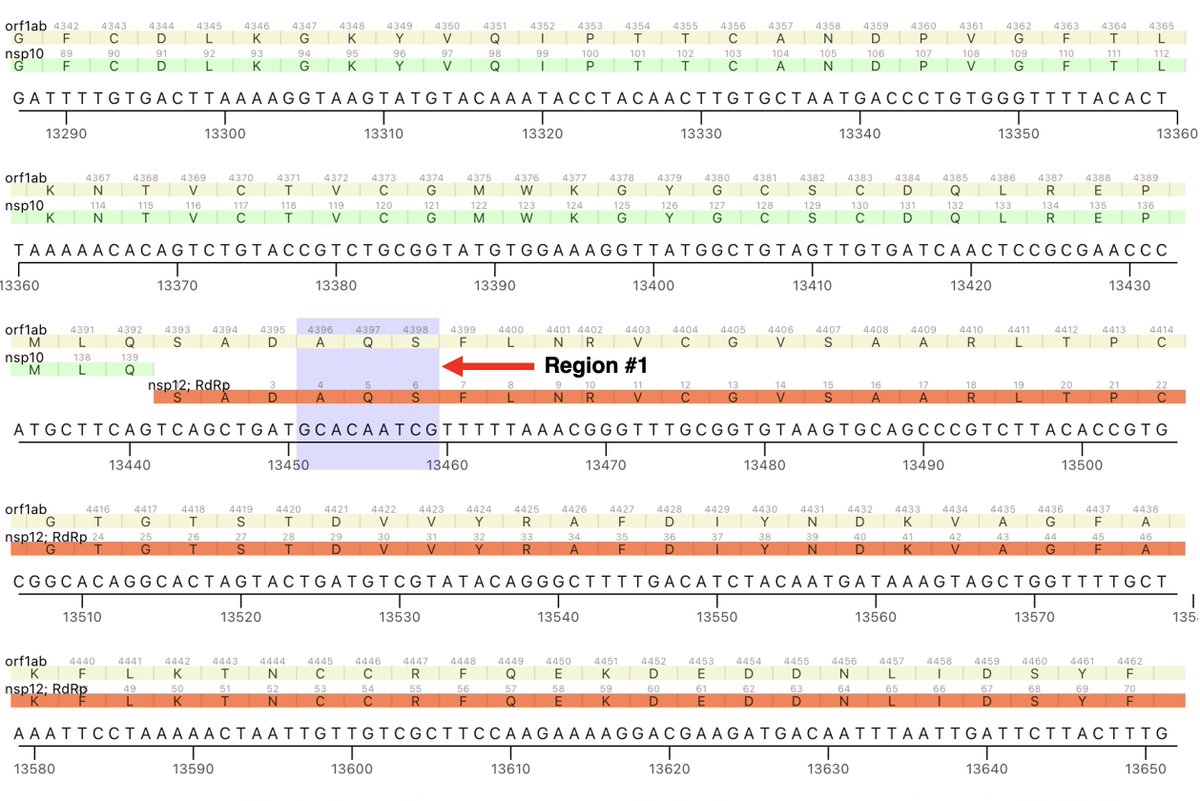

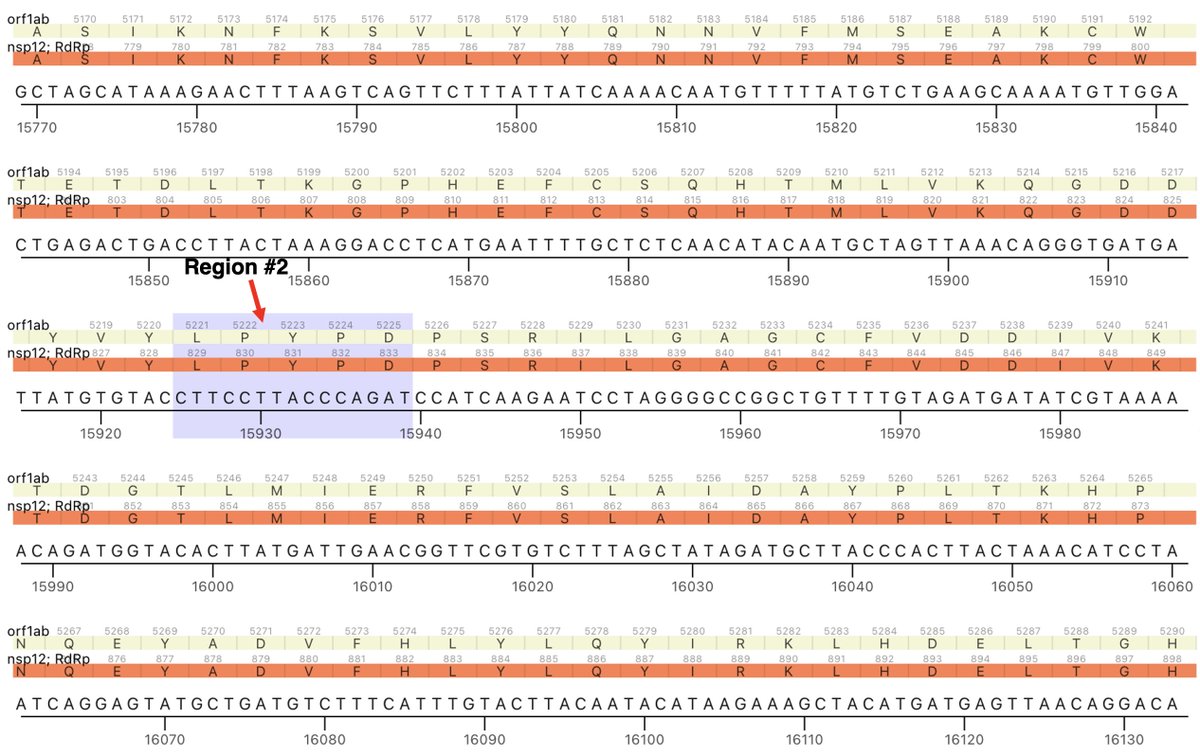

The RdRp copies the same nucleotide twice, shifting its reading frame. The stop codon is bypassed & ORF1b, which includes NSP12-16, is translated. Oddly, the first 1% or so of NSP12 is in ORF1a, with the rest in ORF1b. 5/45

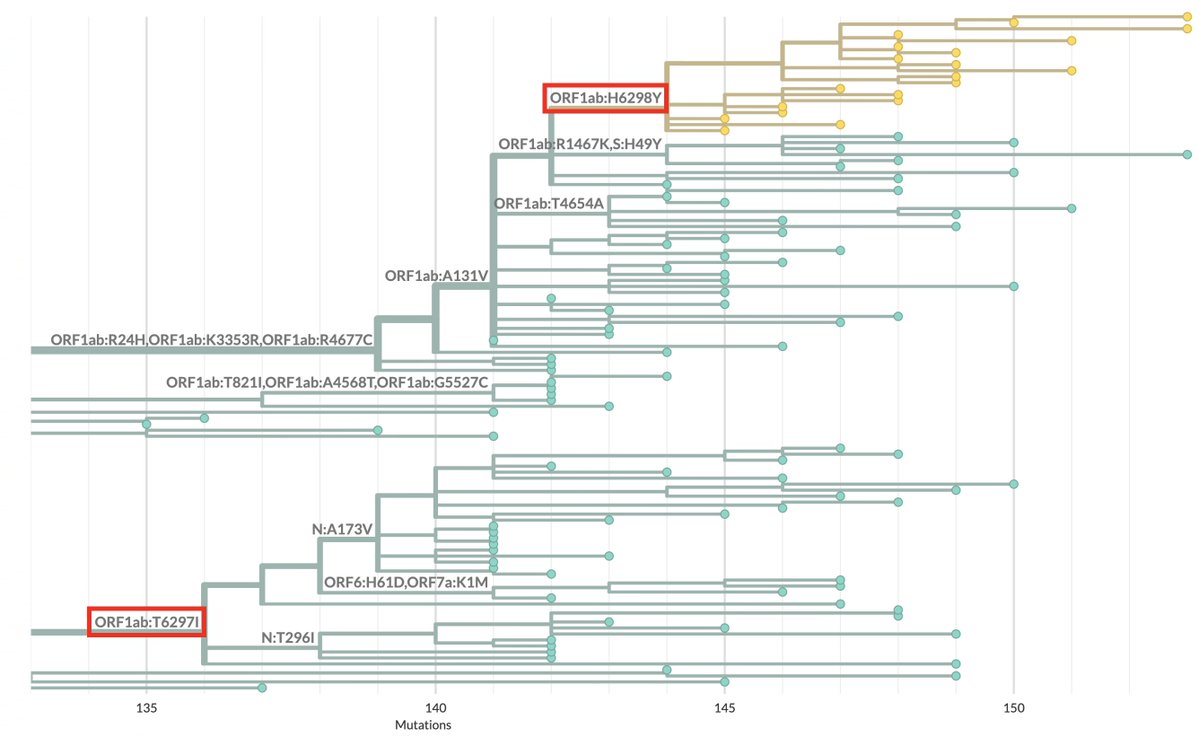

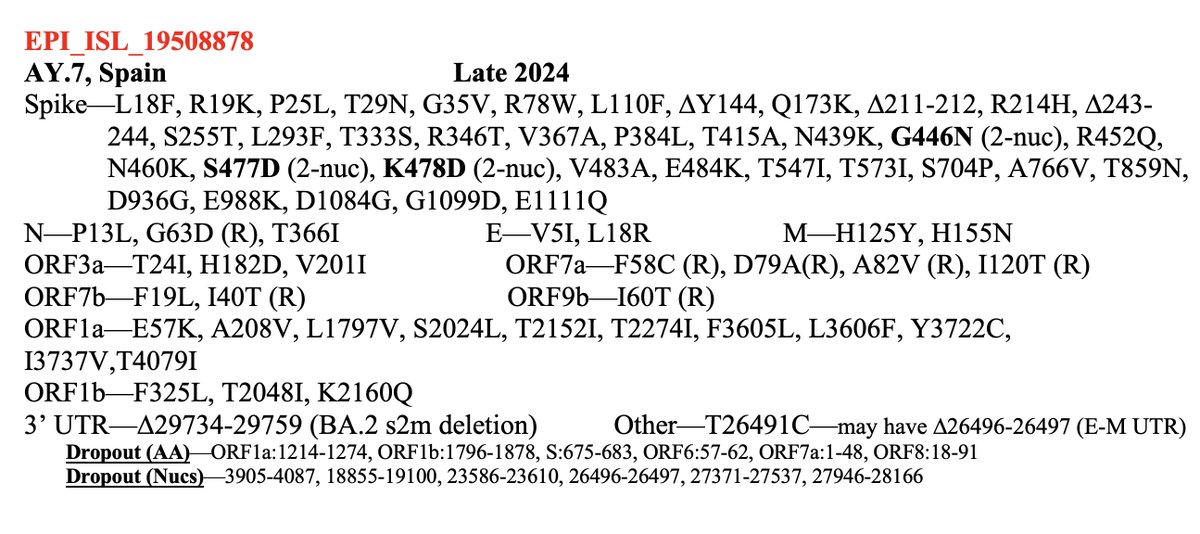

I mention this because the first of the two NSP12 regions in which these paired mutations occur is in ORF1a. The region is ORF1a:4396-4399 (NSP12_4-7), with nearly all being at either ORF1:4396 or ORF1a:4398. 6/45

The other region is ORF1b:820-824 (NSP12_829-833). These two regions are not particularly close to each other in the NSP12/RdRp complex as depicted in structural studies. But there has to be some sort of connection between them. 7/45

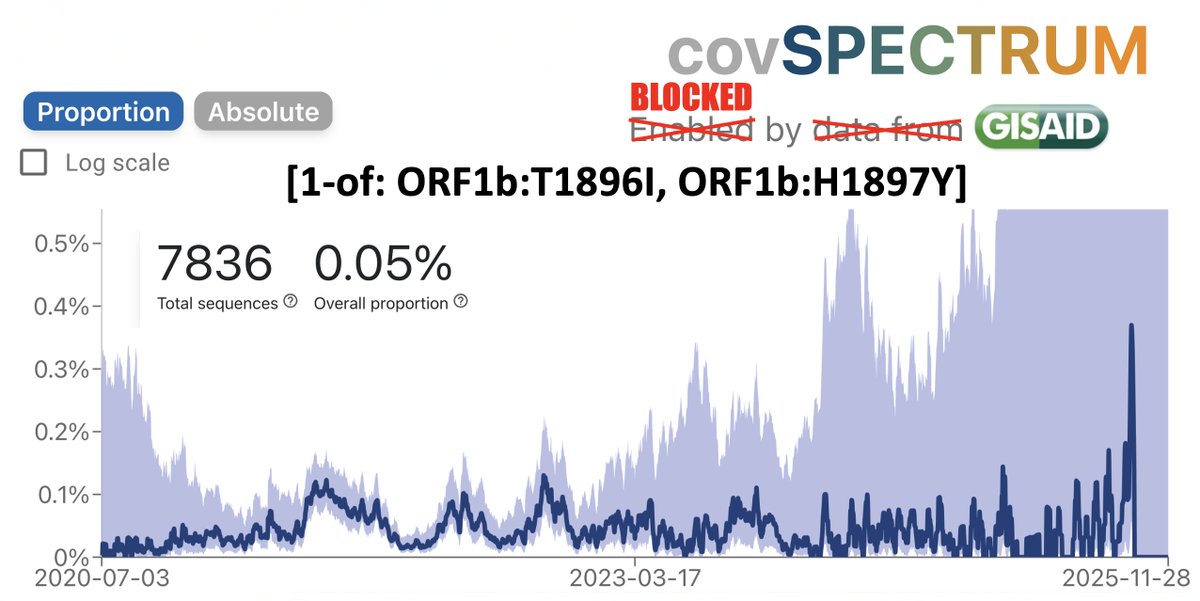

Mutations in both regions are uncommon. In fact, using the legendary @ChaoranChen_‘s CovSpectrum, you can calculate how often we’d expect mutations in these regions to occur together if they had no connection to one another and occurred randomly. 8/45

For simplicity, I’m restricting the analysis to ORF1a:4396 and ORF1a:4398, where the vast majority of these mutations are, though some mutations at 4394, 4395, & 4399 have been also paired with ORF1b:820-824 mutations. 9/45

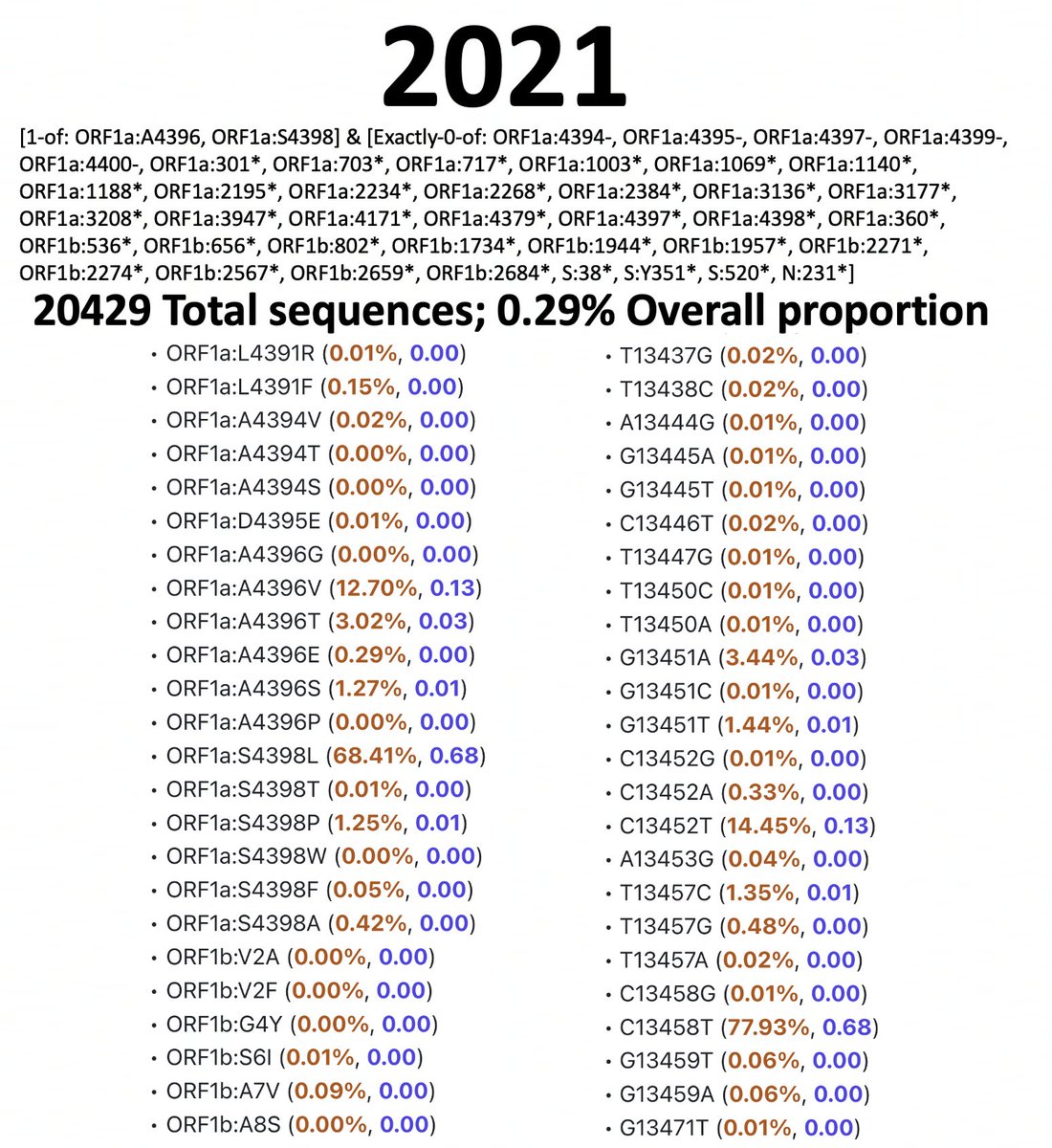

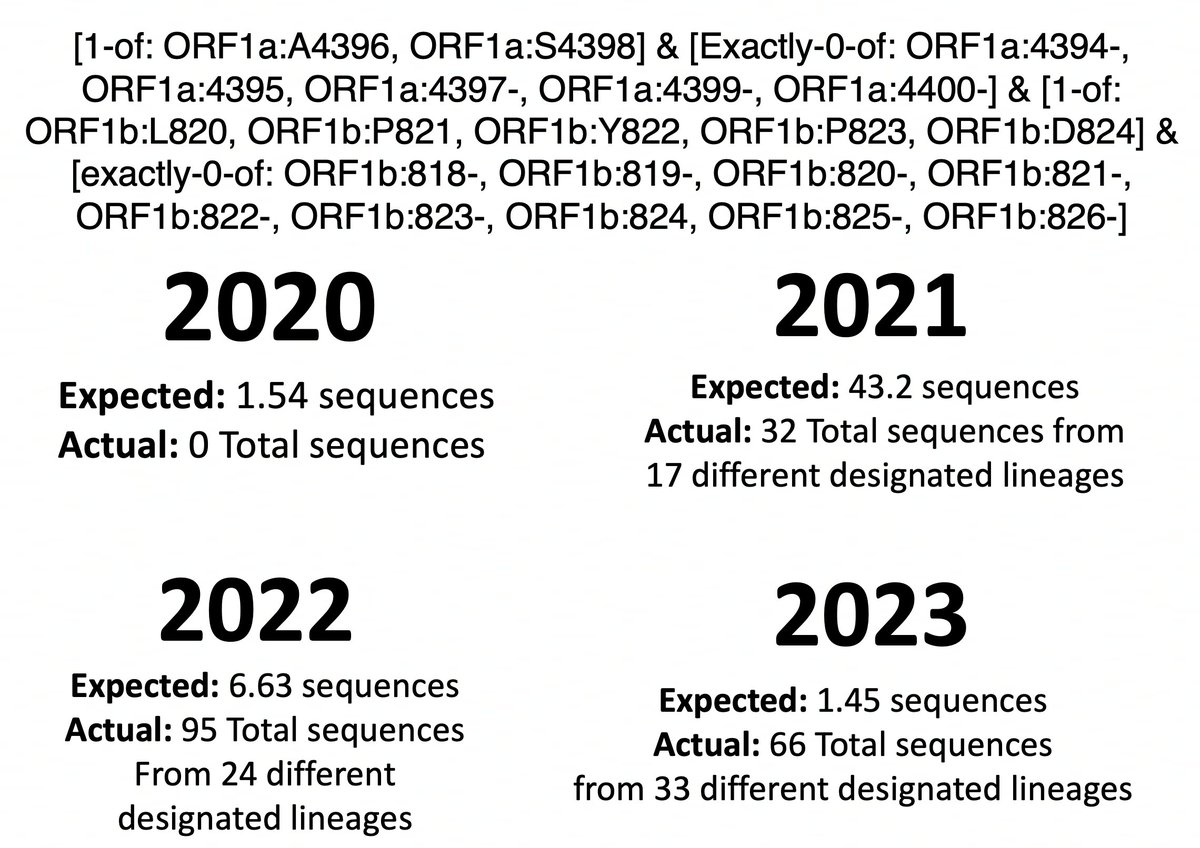

I’ve analyzed 2020, 2021, 2022, & 2023 separately. I spent a long, long time excluding bad sequences from these lists, which is why the queries are complicated. Below are results & queries used for each year for sequences with ORF1a:4396 or ORF1a:4398 mutations. 10/45

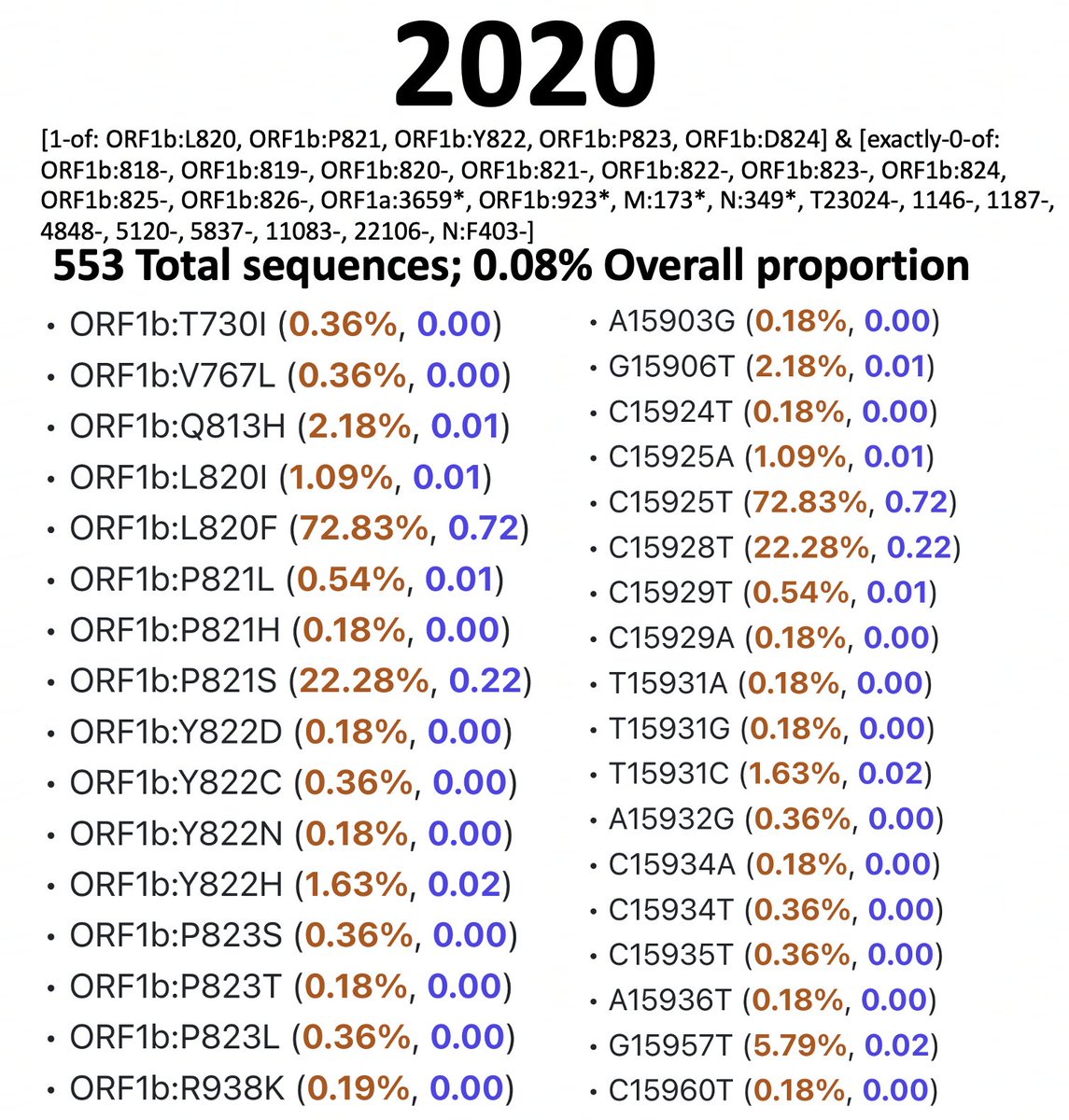

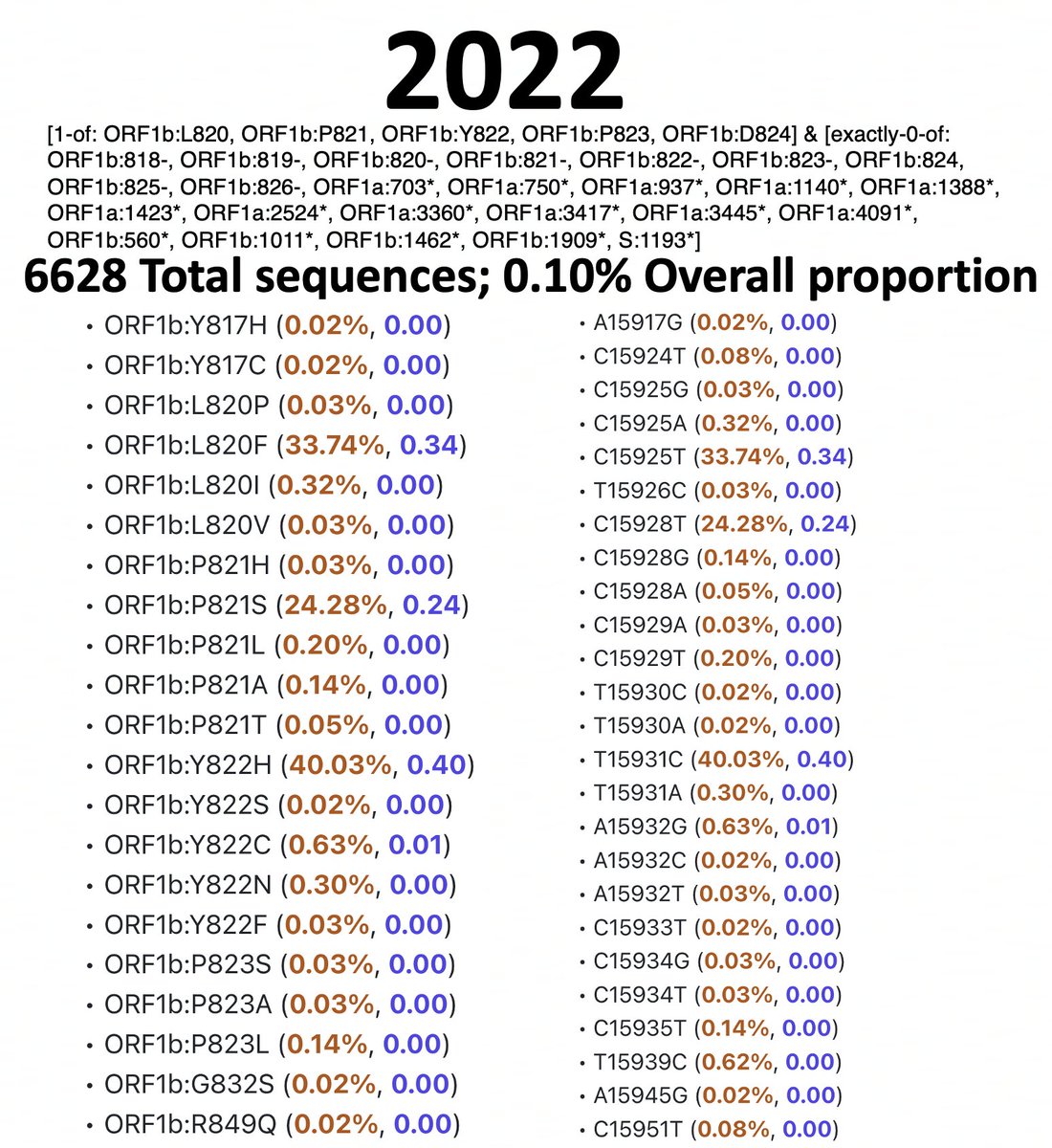

And here are the results & queries used for each year for sequences with a mutation somewhere in ORF1b:820-824. I also filtered these results to exclude any sequence with an SNP clusters score of >99. 11/45

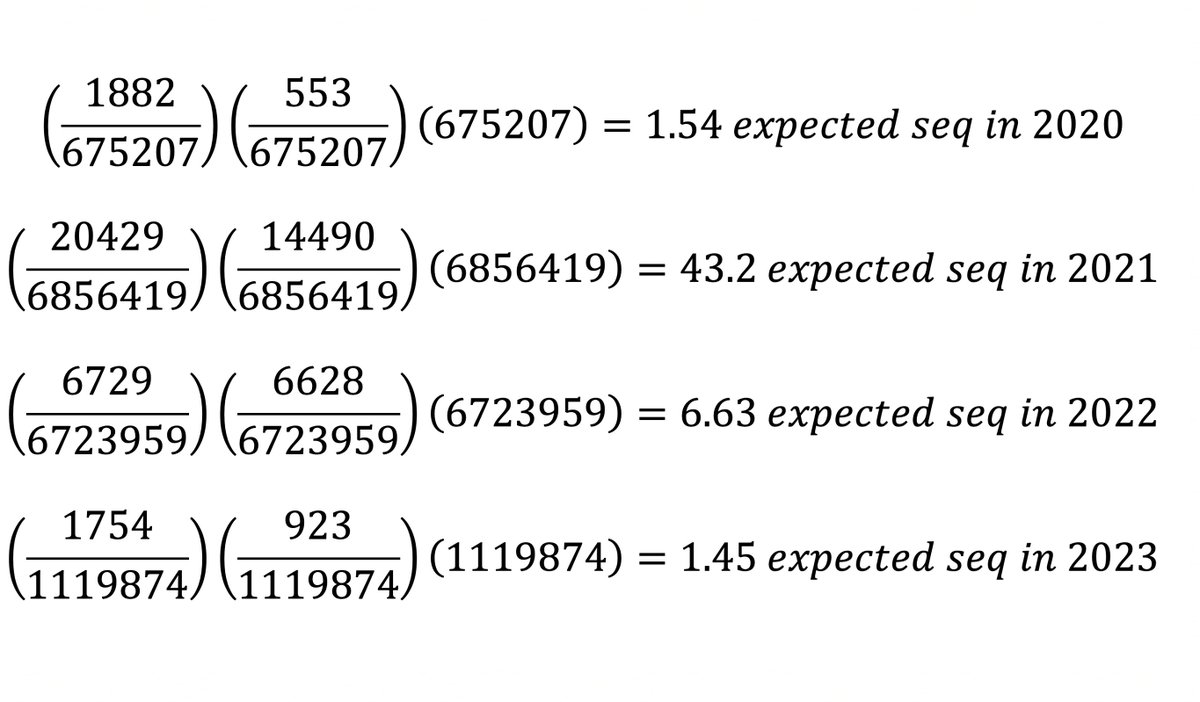

To accurately calculate the number of sequences one would expect to have mutations at both ORF1a:4396/4398 & ORF1b:820-824 (assuming that they occur randomly), you need to know the total number of sequences that have coverage of NSP12. 12/45

To exclude spike-only sequences & those lacking coverage in the NSP12 region, I searched for ORF1b:P314L for each year. This mutation has been universal since mid-2020 (with a handful of extremely interesting exceptions). 13/45

Now it’s a simple matter to calculate (perhaps naively) how many sequences we would expect to have mutations in both regions each year. (% seq w/ORF1a:4396/4398)(% w/ORF1b:820-824)(total seq) = expected number of sequences = not very many.

14/45

14/45

How does the actual number compare? Nothing unusual in 2020 (0 actual vs 1.54 expected) or 2021 (43.2 vs 32), but there seem to be too many sequences with both in 2022 (6.63 vs 95) & 2023 (1.45 vs 66)—i.e. the Omicron era. So this is an Omicron specialty. 15/45

Now you could find thousands of pairs of mutations that are “overrepresented” using the same logic described above. Every decent-sized lineage would have several. It’s really the number of times the mutations were independently acquired that we’re interested in. 16/45

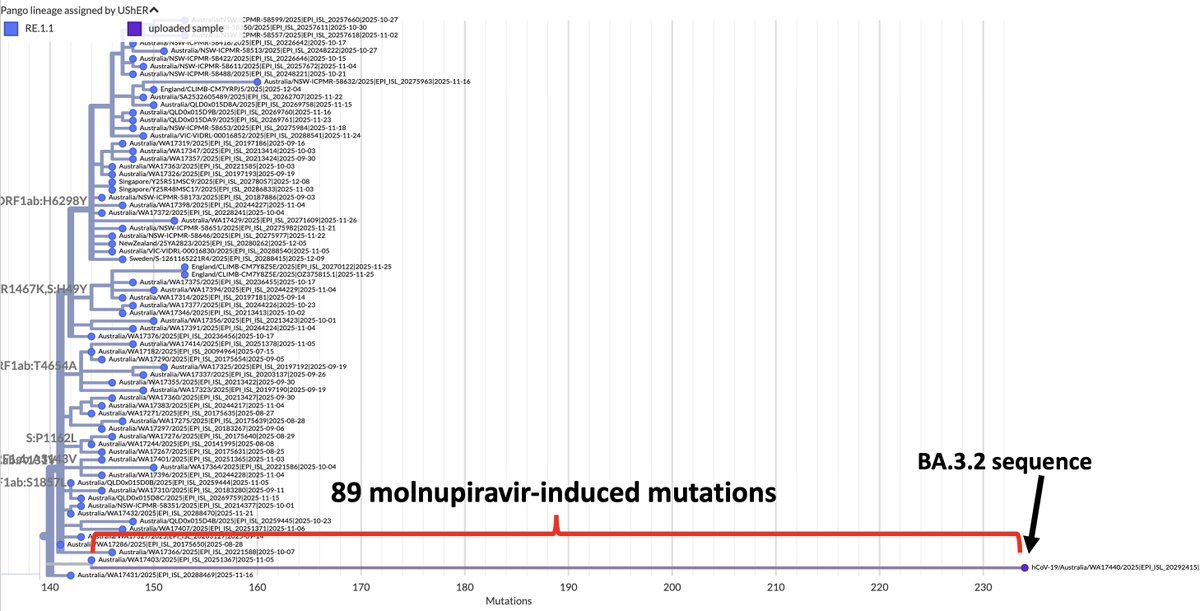

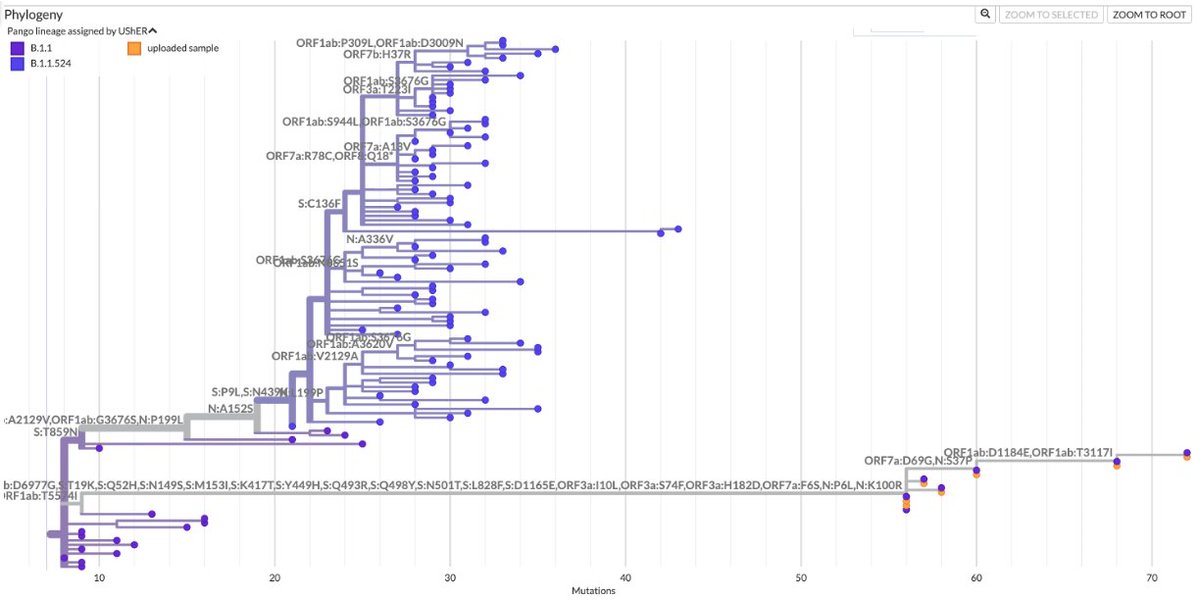

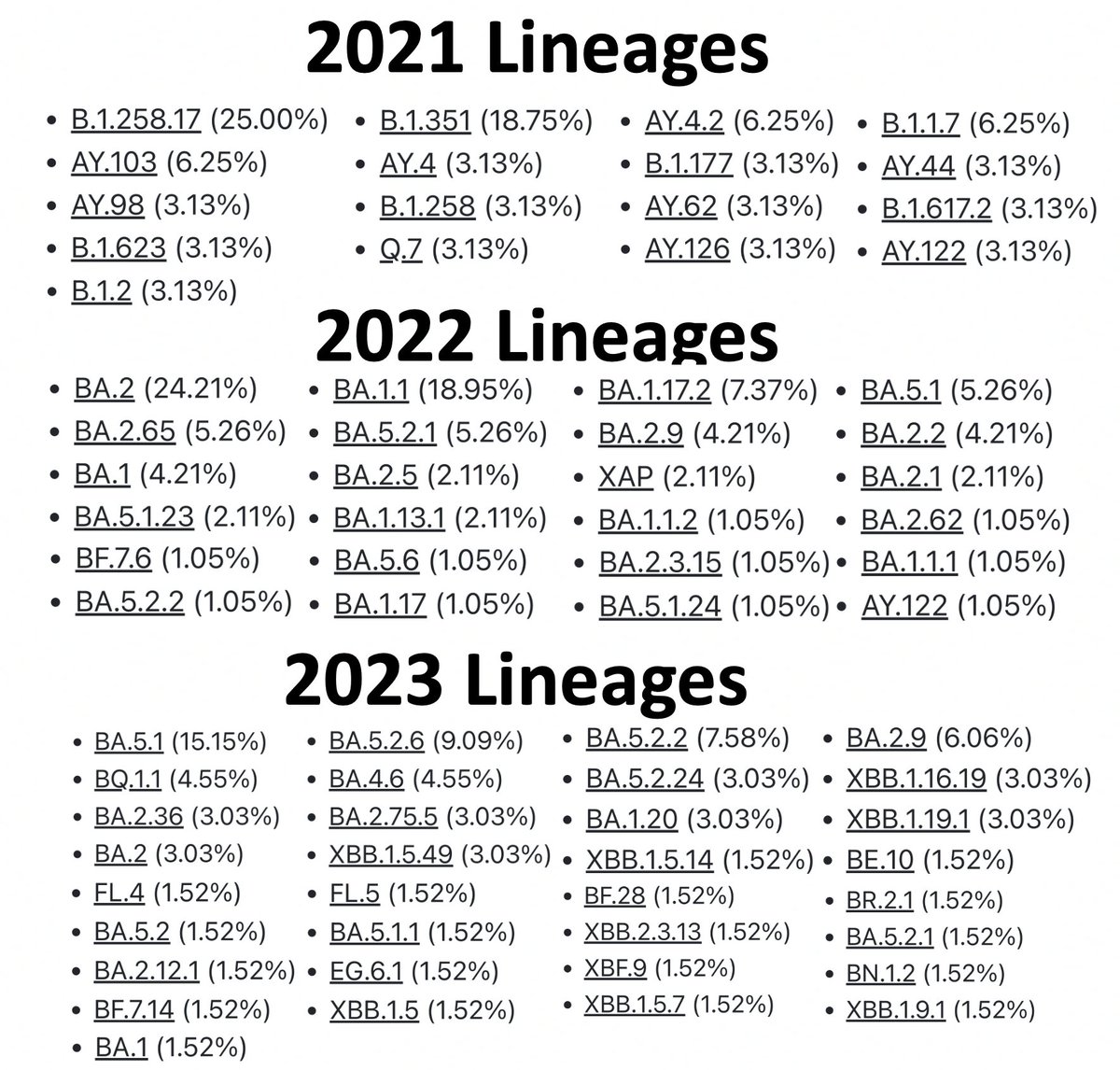

But it turns out that the majority of sequences with ORF1a:4396/4398 + ORF1b:820-824 mutations acquired them independently. I’ve looked at all these sequences individually, but you can tell quickly by looking at the designated lineages of these sequences. 17/45

The 95 sequences w/these paired mutations in 2022 came from 24 different lineages—setting a minimum number of times these mutation-pairs evolved independently. The true number is much larger than 24 since independent acquisition occurred within lineages (e.g. BA.2). 18/45

Examining the Usher trees, I count 65 instances in 2022 (out of the 95 total) that evolved independently. Metadata show that 15/95 seq are 2nd, 3rd, or nth sequences from the same patient, though at least 3 branches involved different patients. 19/45

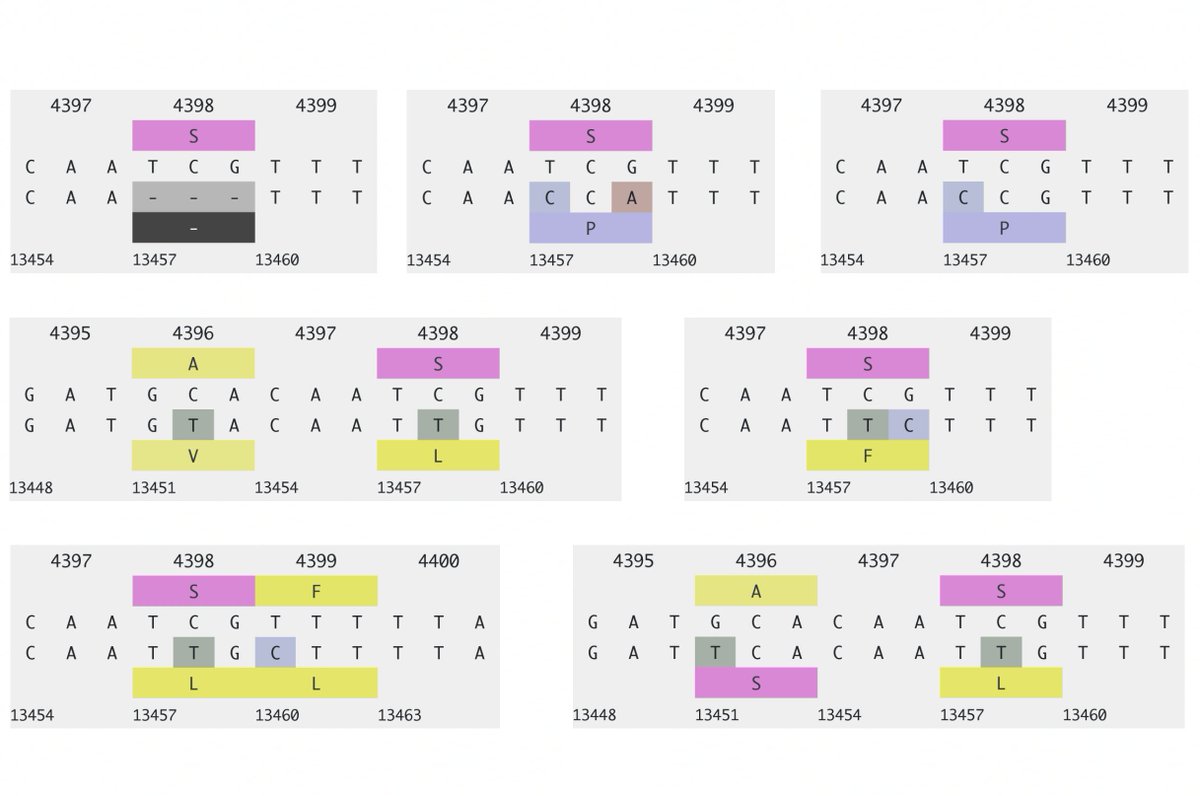

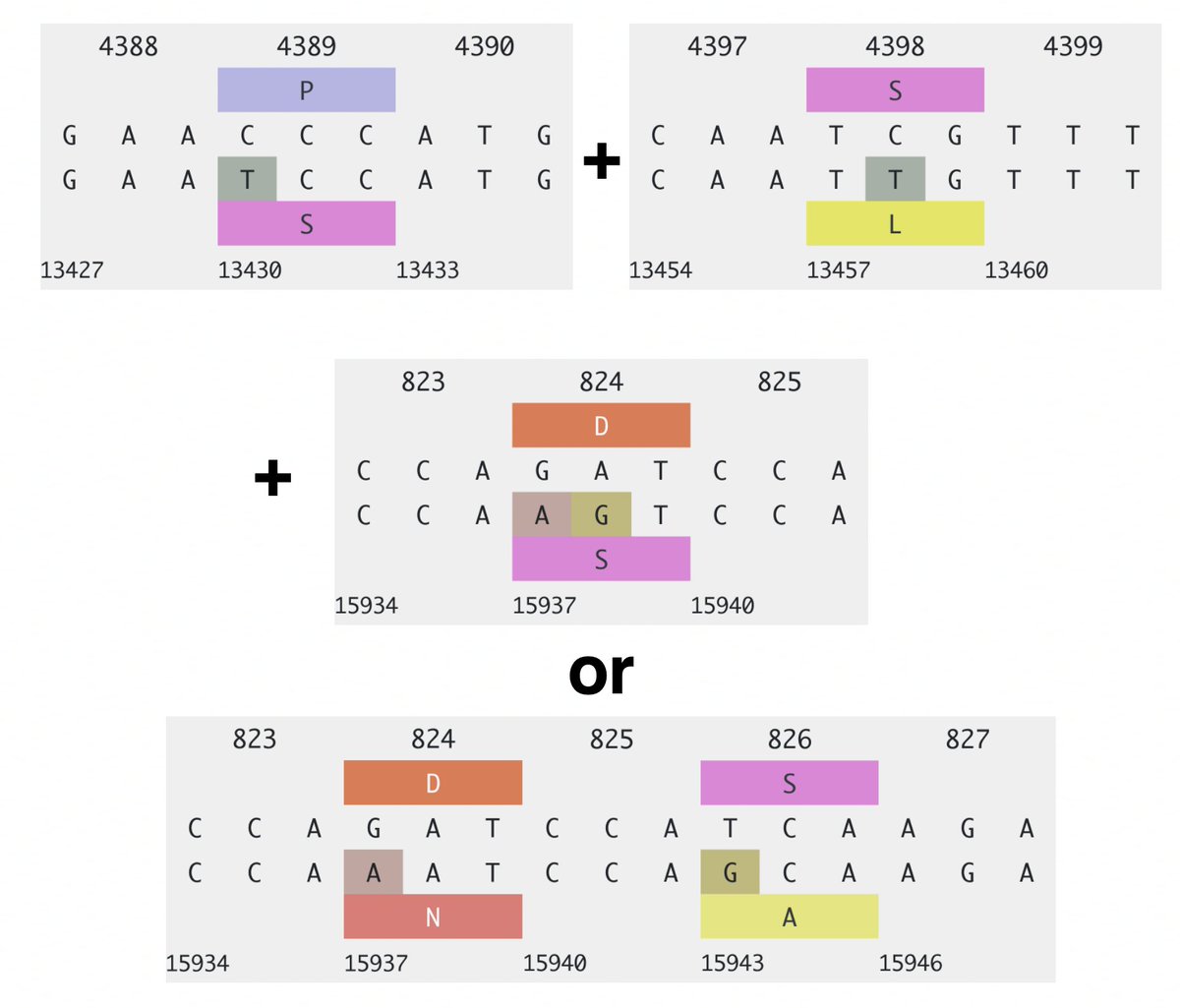

For the 2023 sequences, 37 of 66 sequences represent independent acquisitions of an ORF1a:4396/4398 + ORF1b:820-824 mutational pair. Furthermore, 11 sequences have mutations at *both* ORF1a:4396 & 4398. Some sample specimens depicted below. 20/45

One case for which there are 8 sequences has ORF1a:P4389S, S4398L + ORF1b:D824N/N824S, ORF1b:S826A. Another has ORF1a:S4398L, F4399L + ORF1b:P821S, D824N. Combinations like this cannot be coincidental. 21/45

Most sequences with these mutations are highly divergent, almost certainly originating in chronic infections. (The major exception is a BA.5.1.30 Honk Kong cluster of ~140 sequences). But why should this combo occur in chronic infections? 22/45

Chronic infections can result in rapid accumulation of mutations due to the lack of a transmission bottleneck (& other reasons). I think they also increase the chance of unlikely combinations of mutations. But that doesn’t explain why these mutations should be linked. 23/45

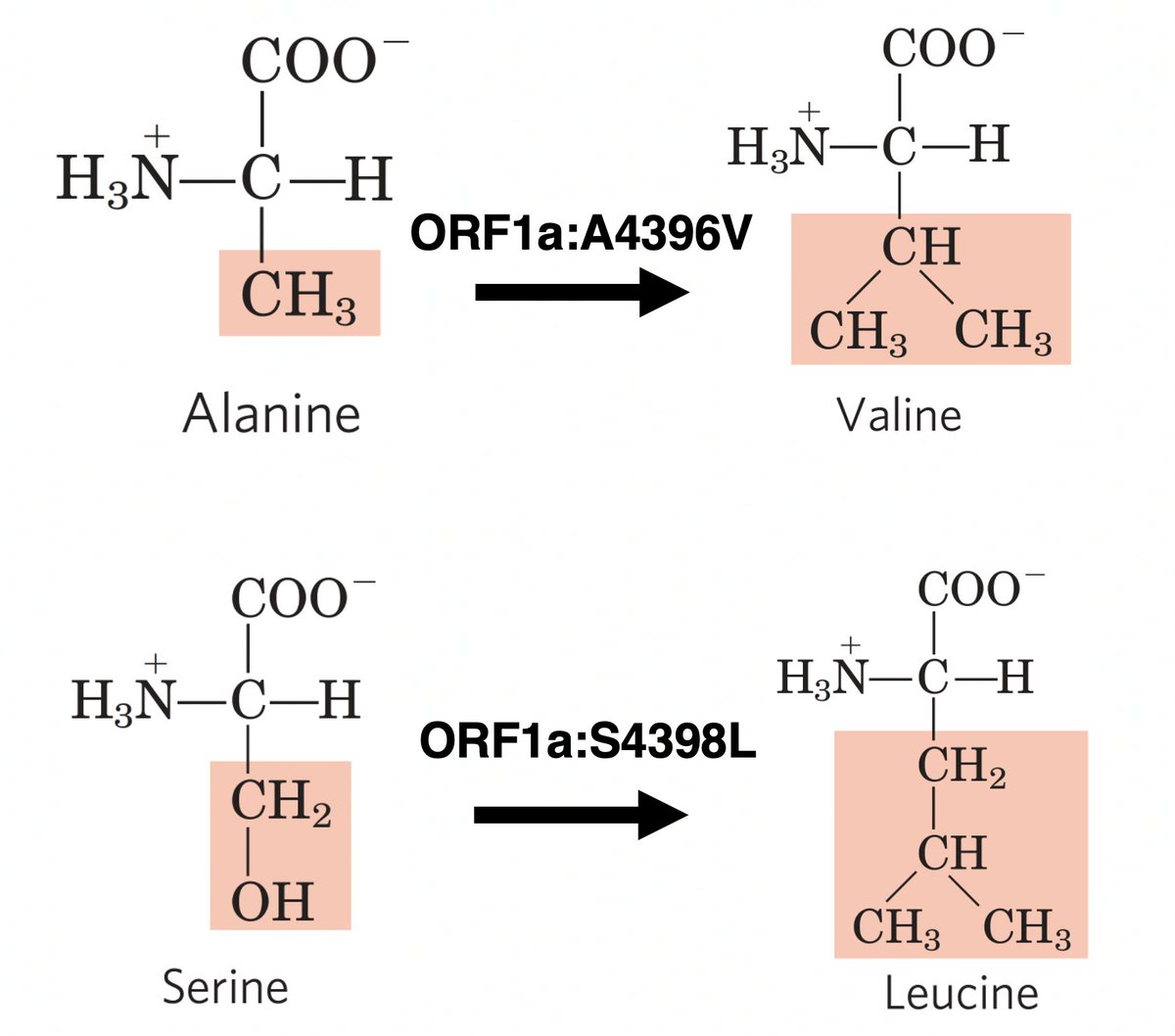

Is there any pattern to the types of mutations? ORF1a:S4398L and ORF1a:A4396V are by far the most common in that region. 24/45

Both ORF1a:A4396V and ORF1a:S4398L result in a somewhat larger and more hydrophobic amino acid. 25/45

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh