A friend of mine and I were recently discussing how to spot quality. I firmly believe that some of the best work today is done by small, independent workshops, not large luxury brands. So I want to highlight one of my favorite makers, Chester Mox.

🔗: tinyurl.com/5n7jf8xr

🔗: tinyurl.com/5n7jf8xr

Part of the problem nowadays is that many people don't know how to spot the more substantive markers for quality, and they can get quickly swept up by brand recognition, the romance of luxury, or celebrity endorsements.

For example, in 2010, the UK Advertising Standards Authority banned a series of Louis Vuitton advertisements. The ads featured paintings that looked like they were made by Johannes Vermeer, and underneath each image was some breathless prose.

One ad read: “A needle, linen thread, beeswax, and infinite patience protect each overstitch from humidity and the passage of time […] With so much attention lavished on every one, should we only call them details?”

The UK banned these ads because they suggest LV's products are handmade when they are not. This is how a lot of luxury goods are sold nowadays. This is not to say the quality is bad—the quality is often good. But it's not at the level many assume when they're spending $$$$$.

Let's go back in time for a moment.

Many of these companies started as small, independent workshops that made high-quality things by hand. That's how they earned their reputation. But with their success came growth and expansion. And later, a shift in focus.

Many of these companies started as small, independent workshops that made high-quality things by hand. That's how they earned their reputation. But with their success came growth and expansion. And later, a shift in focus.

Dana Thomas's book "Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster" covers how the luxury industry has changed over the years. Where brands used to offer superior quality, many are now multi-billion dollar businesses prioritizing growth, brand recognition, and, most importantly, profits.

There are two big reasons why these brands have been watered down:

1. There are fewer craftspeople nowadays, so it's hard to pump out a large number of units at that quality level.

2. When you have a huge overhead and large retail footprint, you have to move *a lot* of units.

1. There are fewer craftspeople nowadays, so it's hard to pump out a large number of units at that quality level.

2. When you have a huge overhead and large retail footprint, you have to move *a lot* of units.

If you want the kind of quality that these luxury brands built their reputation upon, you have to:

1. Find actual craftspeople who are making things, often at a smaller number of units, so they can keep a tight rein on quality.

2. Focus on small businesses, not large brands

1. Find actual craftspeople who are making things, often at a smaller number of units, so they can keep a tight rein on quality.

2. Focus on small businesses, not large brands

Check out Gucci. On their website, they show photos of their history, where serious-looking craftsmen in white coats make leather goods by hand (not a single machine in this photo). These items later adorn the bodies of famous and glamorous people. What heritage! What history!

That heritage, history, and brand reputation are why they're able to charge $2,200 for this simple, exotic leather card case. But when you zoom in, you can see this stitching was done with a sewing machine, not purely by hand. (IMO, the folds are also quite ugly.)

By contrast, let's take a look at some smaller businesses. There are high-quality leathergoods operations in the UK, France, and Japan. These companies are typically run by the craftsperson, not a business person. Your contact is the person who will be making your item.

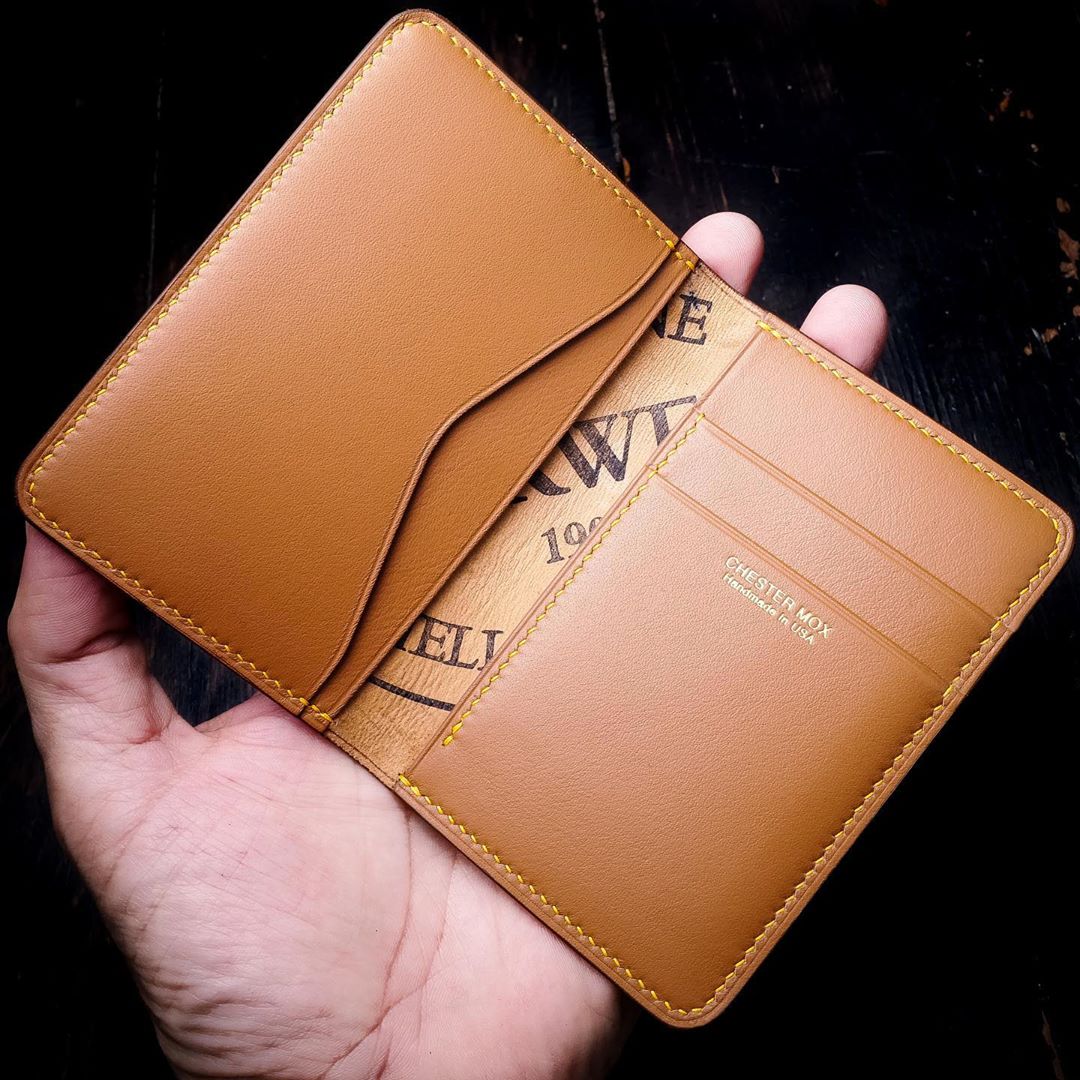

One of my favorites is Chester Mox, a company based in Los Angeles. Bellanie, who runs the operation with her husband Brandon, trained under a former Hermes craftsperson. She makes everything by hand using a technique known as saddle stitching.

Saddle stitching is when two needles pass through the same hole, either with an awl first piercing that hole and guiding a needle through, or with the holes punched by hand using a pricking iron. This is how things are made at Hermes (one of the few luxury brands not yet ruined)

The result is a much more durable seam. Whereas machine stitching can unravel if just one of the threads breaks, you need a special tool to pick apart a saddle-sewn seam.

I also think the resulting seam is much more beautiful. On the left is a machine-sewn RRL eyewear case; on the right is a handsewn Chester Mox card case.

The stitching on the machine-sewn seam runs like this: ----

The stitching on the handsewn seam runs like this: ////

The stitching on the machine-sewn seam runs like this: ----

The stitching on the handsewn seam runs like this: ////

There are machines nowadays that can imitate the /// stitching on a saddle-sewn seam. But what sets really good hand-stitching apart is neatness. These blades are tapered, and a good craftsperson will cut the right-sized hole for the thread's thickness.

They will push the tool just far enough into the leather, relying on muscle memory, so that you don't get gaps between the thread and leather.

Compare the workmanship here to the Gucci card case. Tighter stitching. No ugly fold. (Case can be all exotic leather, if you want)

Compare the workmanship here to the Gucci card case. Tighter stitching. No ugly fold. (Case can be all exotic leather, if you want)

Chester Mox makes all sorts of things: wallets, card cases, eyewear cases, belts, folios, and bags. They use leathers from top-end tanneries, including ones that supply Hermes. They offer monogramming and bespoke services. Edge painting is immaculate.

In practical terms, luxury goods will last you just fine. Objectively speaking, they sell high-quality products. But they are rarely made to the level that people assume. The best things—things made by hand to the highest standards—are more often found at small, indie workshops.

Why buy handmade goods? At a time when machines are increasingly taking over our lives, there is something interesting about more "humanist" forms of production. The authors of Diderot’s Encyclopedia described such items as having "character."

When you buy something that was made by hand, you're not just buying an object, but a testament of someone's skill. You're also supporting someone who is keeping a traditional craft alive.

Ironically, these items often cost less, too. An exotic leather card case from Chester Mox is $330 (compared to $2,200 at Gucci). They also have wallets starting at $75.

IMO, focusing on craftsmanship is a more meaningful conceptualization of luxury than brand recognition.

IMO, focusing on craftsmanship is a more meaningful conceptualization of luxury than brand recognition.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh