A lot of talk about @Karl_Lauterbach's recent talk referencing 3% risk of Long Covid, so I've done a new version of my Cumulative Risk of Developing Long Covid graph, below, incorporating this figure. I'm not sure which study he was referencing.

Some important caveats in the🧵

>

Some important caveats in the🧵

>

(1) The graph assumes that risk from any particular infection neither increases nor decreases. Much like the odds of rolling a 6 remain the same each dice roll, but the more you roll, the more likely you'll eventually get a six. I've seen studies supporting both directions.

>

>

Note that cumulative risk will *always* increase until or unless the per-infection risk goes to zero, which there is currently no evidence to suggest ever happens. If risk decreases, the curves will rise slower. If it increases, they rise quicker

You're always rolling the dice

>

You're always rolling the dice

>

(2) Vaccines appear to both decrease risk of infection, but also risk of developing Long Covid. How much is debatable and likely unknowable given the mass of variants, vaccines, and vaccine uptake.

The risk of developing Long Covid *from* vaccines appears small. Get vaxxed.

>

The risk of developing Long Covid *from* vaccines appears small. Get vaxxed.

>

(3) While it appears that "severity" may increase your risk of Long Covid, it's important to note that the vast vast majority of people who have Long Covid were *not* severly ill or hospitalised.

>

>

Put it this way. Let's imagine 10000 people get a SARS-CoV-2 infection. 1% of them get hospitalised. 99% of them do not. And lets say (hypothetically) the risk of developing Long Covid if hospitalised is *double* if you are hospitalised vs not, say 10% vs 5%.

>

>

What does this *double* risk from severity scenario translate to in reality? Well, most people don't get long covid from this one infection, but 10 people get hospitalised and then get long covid.

495 get a mild acute illness and long covid. Nearly 50 times.

>

495 get a mild acute illness and long covid. Nearly 50 times.

>

(4) I believe now the best way to look at the different risk curves is actually of *severity* rather than risk of contracting Long Covid per se. There are multiple studies suggesting in excess of 50% of people continue to have at least one symptom long after their infection

>

>

Risk of debilitating Long Covid however, is more likely in the 1% to 5% range. You can see from the graph though, the cumulative risk is still significant. Would you hop in a car if the risk of an accident that left you unable to work for months or years (or ever?) was 1 in 20?

>

>

At 5% per infection risk, your cumulative risk exceeds 50% in roughly 13 infections. With people getting infections nearly twice a year (as opposed to twice a decade for influenza), that means in 6 or so years, the odds are you've contracted Long Covid at least once.

>

>

(5) But this also needs to be looked at from a population level. If, say in 4-5 years, the majority of the population has been infected 13+ times, then at 5% risk it means roughly *half* of the population has had a significant illness for months, years - or permanently.

>

>

Are we seeing any evidence this is happening?

Yes, yes we are.

(note: while not shown in the graph, the trend was flat for the years prior to the pandemic)

> ons.gov.uk/employmentandl…

Yes, yes we are.

(note: while not shown in the graph, the trend was flat for the years prior to the pandemic)

> ons.gov.uk/employmentandl…

That data was from the UK, but it's important to note the proposed policy response to this crisis -

Force people back to work.

Similar responses have been promoted elsewhere. This of course means future statistics will not be comparable.

>

itv.com/news/2023-11-1…

Force people back to work.

Similar responses have been promoted elsewhere. This of course means future statistics will not be comparable.

>

itv.com/news/2023-11-1…

(6) this issue of data comparability is important for all of this data over time. Getting tested for Covid is becoming rarer and rarer. This means that attributing long term issues to covid will become harder and harder.

>

>

What does this mean in practice?

It means that even if Long Covid prevalence increases as per the cumulative risk modelling, *it will be very difficult, if not impossible, for a research project to show it*

>

It means that even if Long Covid prevalence increases as per the cumulative risk modelling, *it will be very difficult, if not impossible, for a research project to show it*

>

In self-report surveys, if you believe you haven't had Covid recently, and you have some ongoing symptom, you're not going to attribute it to Covid, are you?

Same for official diagnoses of Long Covid and studies with ostensibly "uninfected" controls.

>

Same for official diagnoses of Long Covid and studies with ostensibly "uninfected" controls.

>

Until we have a well-established test for Long Covid, future prevalence data is going to be increasingly unreliable, I don't see a way around this.

In the meantime, policy makers *must* consider the implications. This may not happen. Or it may. But the risk cannot be ignored.

>

In the meantime, policy makers *must* consider the implications. This may not happen. Or it may. But the risk cannot be ignored.

>

Please forward this to policy makers in your country.

@jakobforssmed @europeapatient @Folkhalsomynd @ECDC_EU @TheWHN @cdc @domk

@jakobforssmed @europeapatient @Folkhalsomynd @ECDC_EU @TheWHN @cdc @domk

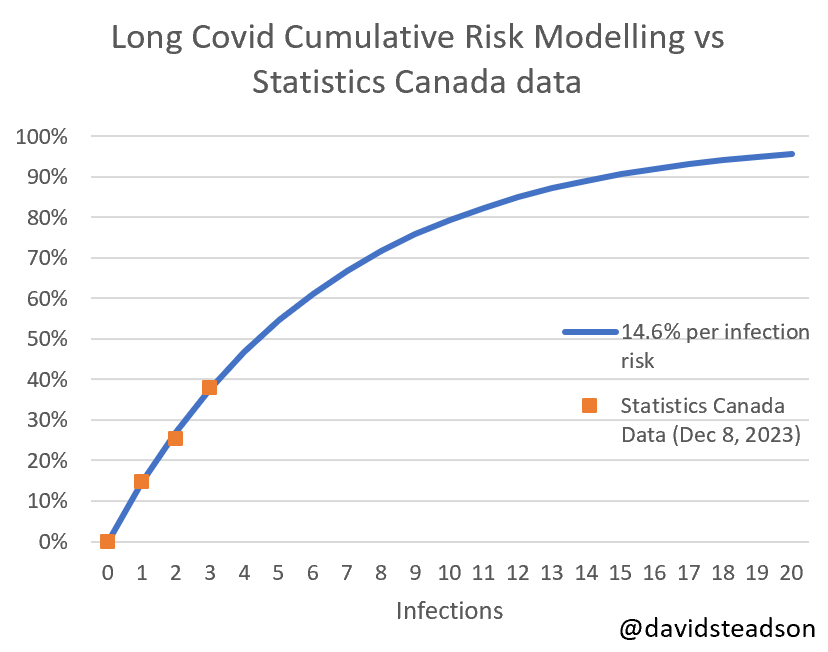

Less than 24hrs after I did this thread, @StatCan_eng published the first report I have seen on prevalence of ever having contracted Long Covid by 1st, 2nd, and 3rd infection. They found a 1st infection prevalence of 14.6%. So I plugged that in to my model, with their findings.

The first infection is the same because it's the model input -> 14.6% risk. The 2nd and 3rd infection data fit the model astoundingly well and is the first evidence that per infection risk is likely relatively independent. No one study is ever truth however, more data is needed.

Here is a link to the paper.

https://x.com/StatCan_eng/status/1733222476207861991?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh