LONG COVID, a 🧵

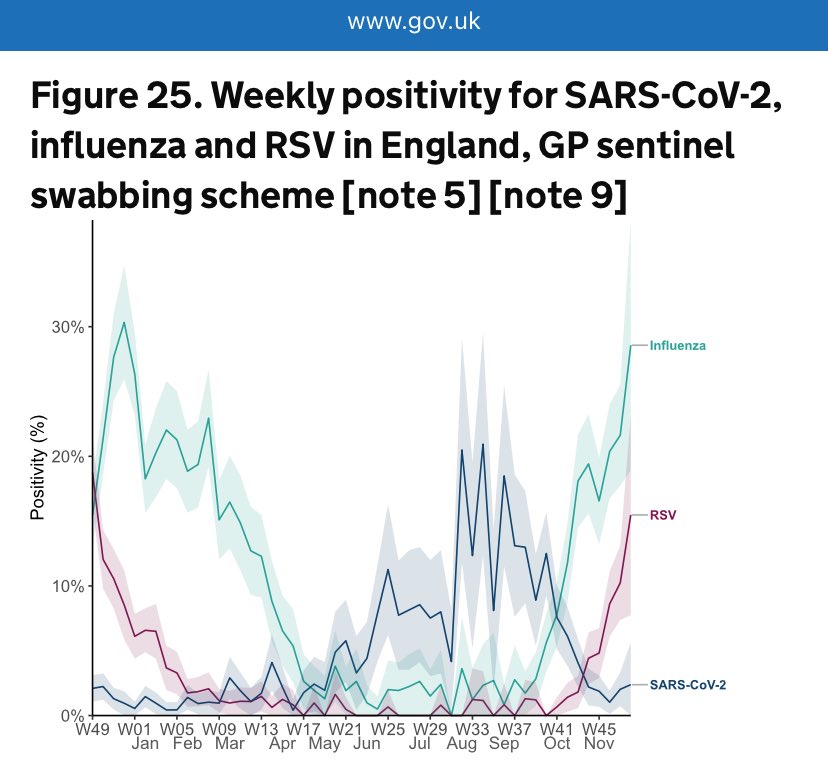

Long Covid prevalence is no longer tracked in the UK so it’s useful to see data from other countries.

A new study from Canada was published this week which led with the shocking statistic that:

📍1 in 9 Canadian adults have experienced long-Covid symptoms…

Long Covid prevalence is no longer tracked in the UK so it’s useful to see data from other countries.

A new study from Canada was published this week which led with the shocking statistic that:

📍1 in 9 Canadian adults have experienced long-Covid symptoms…

https://twitter.com/statcan_eng/status/1733222476207861991

Of the 1 in 9 Canadian adults who have experienced Long Covid since the start of the pandemic:

📍80% experienced symptoms for at least 6 months or more;

📍58% are still continuing to experience long-term symptoms as of June 2023, ie. they have never recovered.

📍80% experienced symptoms for at least 6 months or more;

📍58% are still continuing to experience long-term symptoms as of June 2023, ie. they have never recovered.

But perhaps the most interesting thing in this report is this chart which looks at the impact of cumulative infections.

The risk of developing Long Covid symptoms is:

📍15% after 1 infection

📍25% after 2 infections

📍38% after 3+ infections - that’s 1 in every 2.6 people!

The risk of developing Long Covid symptoms is:

📍15% after 1 infection

📍25% after 2 infections

📍38% after 3+ infections - that’s 1 in every 2.6 people!

Let’s just take a moment to appreciate that statistic.

📍38% of Canadian adults reporting 3 or more Covid infections had experienced Long Covid symptoms.

These figures make it quite clear that the more infections people have, the higher the risk is.

📍38% of Canadian adults reporting 3 or more Covid infections had experienced Long Covid symptoms.

These figures make it quite clear that the more infections people have, the higher the risk is.

You might wonder what this looks like if you extrapolate it out further.

Well, @DavidSteadson has developed a model for just that.

This chart shows the cumulative probability of developing Long Covid at different estimates of risk for each additional new infection…

Well, @DavidSteadson has developed a model for just that.

This chart shows the cumulative probability of developing Long Covid at different estimates of risk for each additional new infection…

Plugging the figures for the risk of Long Covid from 1st, 2nd & 3rd infection from the Canadian survey into David’s model, it’s incredible how well the data fits the curve.

Worryingly, this model estimates that, after 10 infections, you have an ~80% chance of having Long Covid.

Worryingly, this model estimates that, after 10 infections, you have an ~80% chance of having Long Covid.

https://twitter.com/davidsteadson/status/1733246635231097280

To anyone who’s been paying attention to the scientific research, these numbers will come as no big surprise.

The CDC estimate that ~1 in 5 adults now have a health condition that may be related to their previous Covid infection.

That’s 20% of us!

The CDC estimate that ~1 in 5 adults now have a health condition that may be related to their previous Covid infection.

That’s 20% of us!

Here in the UK, Long Covid stopped being officially tracked in March.

At that time, ONS estimated that nearly 2 MILLION people were suffering from Long Covid - that’s nearly 3% of the entire population!

Of these, around 700k developed Long Covid since the Omicron era began.

At that time, ONS estimated that nearly 2 MILLION people were suffering from Long Covid - that’s nearly 3% of the entire population!

Of these, around 700k developed Long Covid since the Omicron era began.

We also know that Covid can cause significant long-term sequelae which may not always be linked back to a previous infection.

For example, a recent study by the BHF found that people who caught Covid were 5x more likely to die from heart disease in the 18 months after infection.

For example, a recent study by the BHF found that people who caught Covid were 5x more likely to die from heart disease in the 18 months after infection.

And, as this BBC article acknowledges, it’s very likely that at least some of the deaths which were (or will be) hastened by the after-effects of a Covid infection will *not* end up being linked to the virus when the death is registered.

bbc.co.uk/news/health-64…

bbc.co.uk/news/health-64…

The CDC even added an update to their guidance for certifying ‘Deaths due to Covid’, making it clear that clinicians should bear in mind that Covid “can have lasting effects on nearly every organ of the body for weeks, months & potentially years after infection.”

But for many, death is not the biggest risk.

Long-term chronic illness is.

Since the start of the pandemic, we’ve seen a huge rise in the number of people dropping out of the workforce altogether due to long term sickness, reaching an all-time high of 2.6 million as of July.

Long-term chronic illness is.

Since the start of the pandemic, we’ve seen a huge rise in the number of people dropping out of the workforce altogether due to long term sickness, reaching an all-time high of 2.6 million as of July.

According to a discussion paper recently published by the Institute for Public Health Research, long-term sickness absence is now a ‘serious fiscal threat’ in the U.K.

They have called for urgent action to tackle this ‘tide of sickness’ head-on.

ippr.org/files/2023-09/…

They have called for urgent action to tackle this ‘tide of sickness’ head-on.

ippr.org/files/2023-09/…

And, as the Canadian study at the top of this thread showed, it’s clear that the risk of developing Long Covid increases with each successive reinfection.

Just because you’ve had Covid before and were fine, it doesn’t mean you’ll be fine next time…

nature.com/articles/s4159…

Just because you’ve had Covid before and were fine, it doesn’t mean you’ll be fine next time…

nature.com/articles/s4159…

We also know that Long Covid can strike anyone, even those who only had mild symptoms during the ‘acute’ phase.

In fact, studies have shown that 90% of people suffering from Long Covid initially experienced only mild illness with COVID-19.

fortune.com/2023/01/05/ori…

In fact, studies have shown that 90% of people suffering from Long Covid initially experienced only mild illness with COVID-19.

fortune.com/2023/01/05/ori…

There are so many studies now… all coming to the same conclusion:

That Covid causes multi-organ damage which persists long after the acute phase.

Covid is not, and will never be, ‘just a cold’.

nature.com/articles/s4157…

That Covid causes multi-organ damage which persists long after the acute phase.

Covid is not, and will never be, ‘just a cold’.

nature.com/articles/s4157…

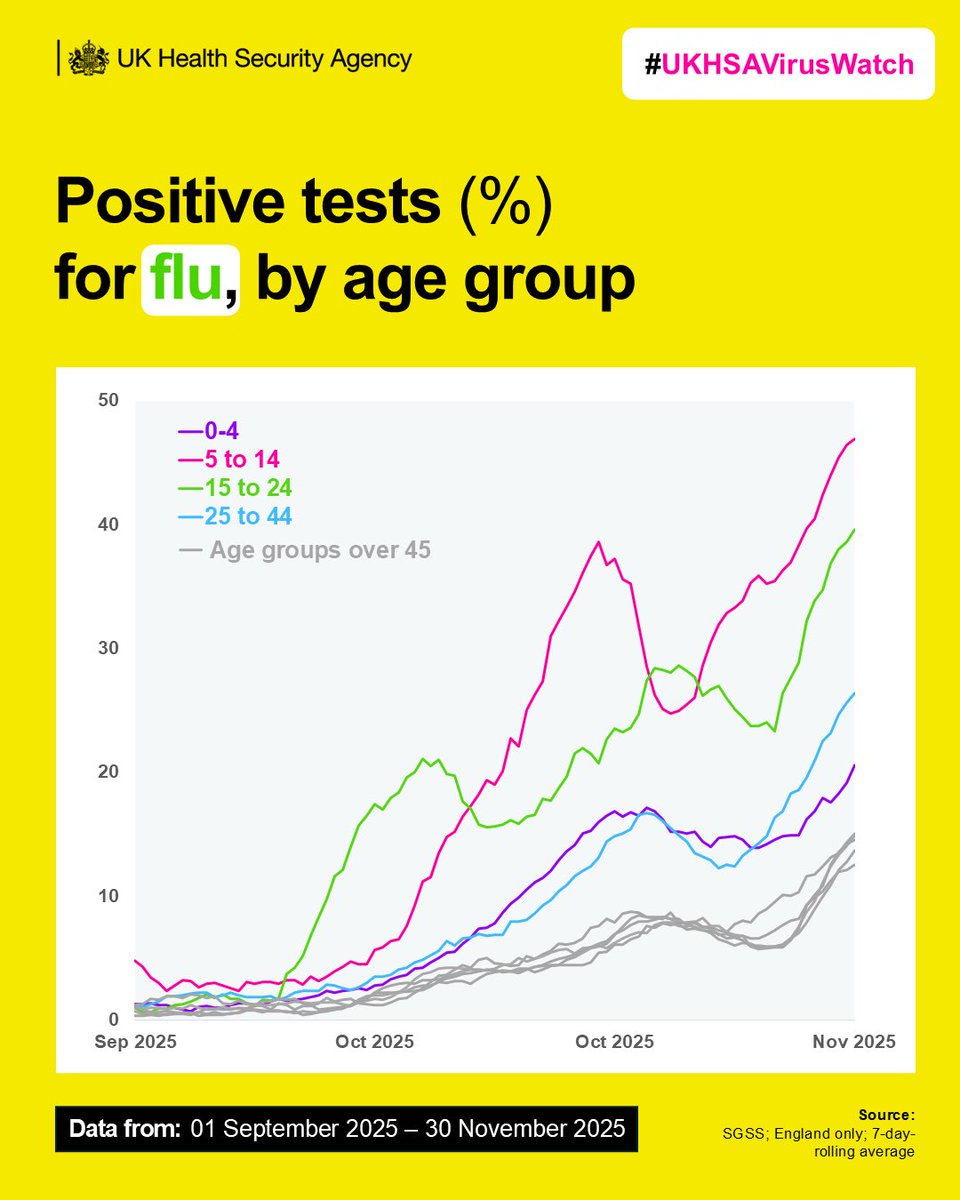

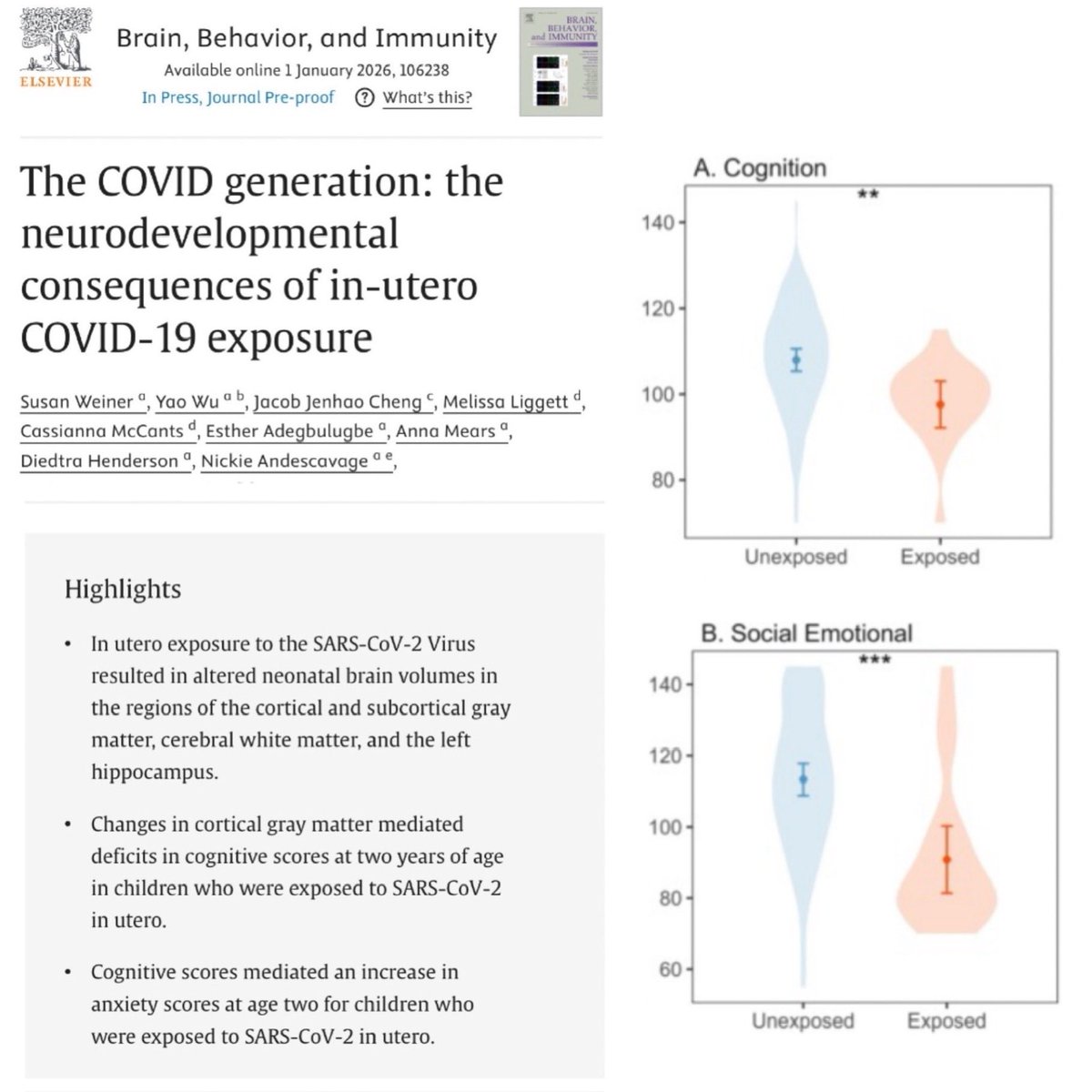

Covid’s effect on the brain is particularly concerning.

In the thread 🧵 below, I’ve compiled a number of scientific studies from around the world, all of which examine the long-term impact of Covid infection on the brain.

None of it is good.

In the thread 🧵 below, I’ve compiled a number of scientific studies from around the world, all of which examine the long-term impact of Covid infection on the brain.

None of it is good.

https://twitter.com/_catinthehat/status/1668577909836075008

I could keep posting studies like this all day long, but instead I’ll direct you to this link where @JessicaLexicus has collated a list of 171 sources explaining the long-term harm that Covid can cause to your vital organs

It’s well worth taking a look.

raindrop.io/JW_Lists/resea…

It’s well worth taking a look.

raindrop.io/JW_Lists/resea…

Despite all this evidence, most people are blissfully unaware of the risks of repeated Covid infections.

Meanwhile, scientists are sounding the alarm, warning that ‘the oncoming burden of Long Covid is so large as to be unfathomable’.

What will it take to get people to listen?

Meanwhile, scientists are sounding the alarm, warning that ‘the oncoming burden of Long Covid is so large as to be unfathomable’.

What will it take to get people to listen?

https://twitter.com/natrevimmunol/status/1678740068754653184

Sadly, the media and government have done a truly appalling job of raising awareness of the risk of Long Covid.

It appears they are following the “don’t look up” strategy and we’re currently stuck in the “sit tight & assess” phase…

It appears they are following the “don’t look up” strategy and we’re currently stuck in the “sit tight & assess” phase…

But there are a few exceptions… a few brave politicians who have been prepared to speak out about this.

Just last week, the German Health Minister made a very powerful speech discussing the long-term harms of Covid.

I’ve written up part of his speech from the video below 👇🏻

Just last week, the German Health Minister made a very powerful speech discussing the long-term harms of Covid.

I’ve written up part of his speech from the video below 👇🏻

https://twitter.com/zurnull/status/1731941221503812060

And then, of course, there’s the formidable @CassyOConnor_ (MP for Clark, Tasmania until her resignation in July 2023) who gave an absolute masterclass in holding politicians to account back in June, asking the critical questions to confront the elephant in the room…

https://twitter.com/_catinthehat/status/1666365630071681024

There are also a few brave journalists bold enough to speak the truth about Long Covid, journalists like @GeorgeMonbiot.

amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/…

amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/…

@GeorgeMonbiot When are people going to wake up & realise the enormous implications of getting repeatedly infected with Covid multiple times a year?

We could be doing so much more to reduce the spread of Covid in schools, hospitals, workplaces.

But first, we need the tide of opinion to turn.

We could be doing so much more to reduce the spread of Covid in schools, hospitals, workplaces.

But first, we need the tide of opinion to turn.

https://twitter.com/_catinthehat/status/1715638858883174579

I don’t know when the tipping point will come… but it had better come soon.

Already the economic impact of Long Covid in the UK alone is estimated to be £534 BILLION (see thread 🧵below ).

And it’s only going to keep getting worse unless something is done about it…

Already the economic impact of Long Covid in the UK alone is estimated to be £534 BILLION (see thread 🧵below ).

And it’s only going to keep getting worse unless something is done about it…

https://twitter.com/_catinthehat/status/1711746097331192176

Apologies, minor typo in this tweet.

I should have written “Institute for Public 𝙋𝙤𝙡𝙞𝙘𝙮 Research”, not “Institute for Public 𝙃𝙚𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙝 Research”.

Oh, for an edit button!!

I should have written “Institute for Public 𝙋𝙤𝙡𝙞𝙘𝙮 Research”, not “Institute for Public 𝙃𝙚𝙖𝙡𝙩𝙝 Research”.

Oh, for an edit button!!

https://twitter.com/_catinthehat/status/1734224490236727615

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh