Yes, all things considered, Jackson did an admirable job of bringing LotR to the screen.

But he and the ladies who wrote the screenplay made some inexplicable alterations to Tolkien's story. This is one of the most egregious.

But he and the ladies who wrote the screenplay made some inexplicable alterations to Tolkien's story. This is one of the most egregious.

It’s in keeping with the larger alterations they made to Aragorn’s character, robbing him of his magnanimity.

The real Aragorn is not a reluctant king. He knows precisely who he is and what he must do.

The real Aragorn is not a reluctant king. He knows precisely who he is and what he must do.

https://twitter.com/ChivalryGuild/status/1648463680735162372

The difference between book-Aragorn and movie-Aragorn is most apparent in the depiction of his encounter with Sauron in the Palantir.

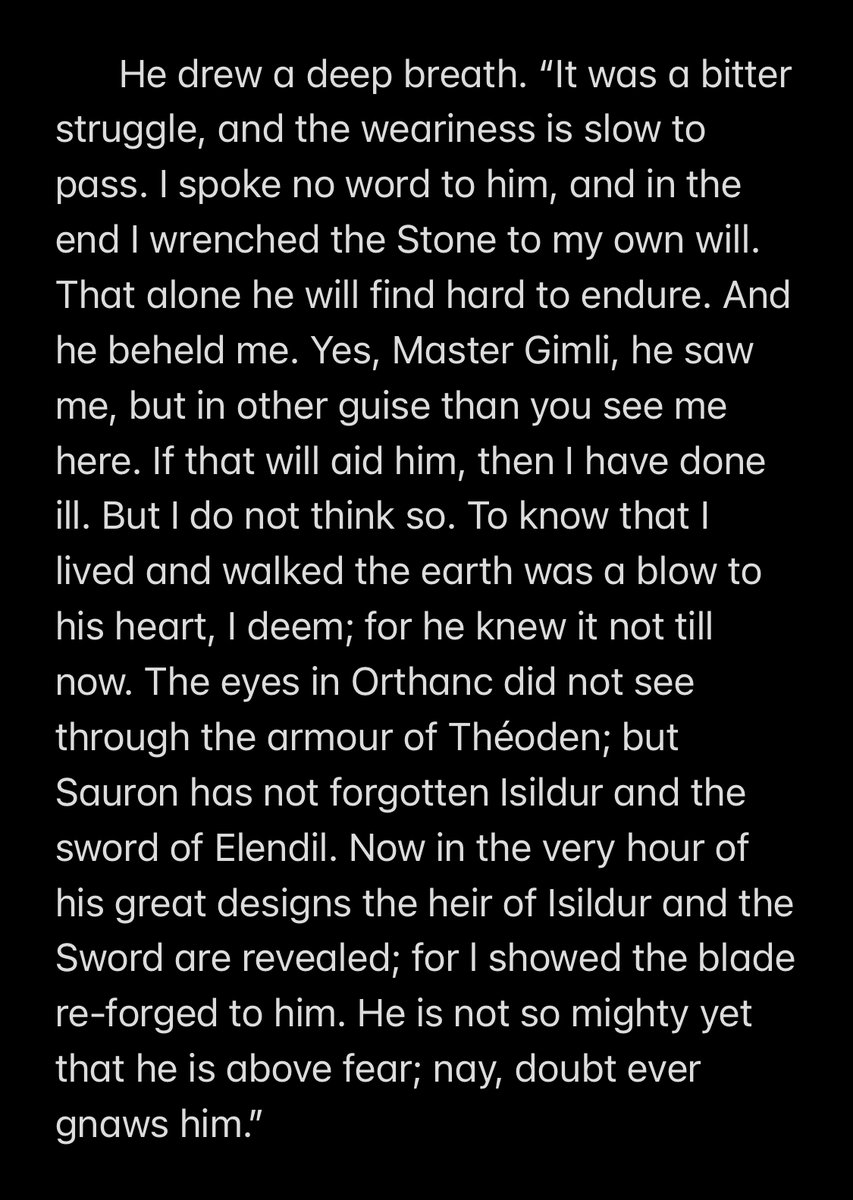

Here's Tolkien:

Here's Tolkien:

Perhaps no passage in a book has ever charged me up the way the way that one did. This was an expression of greatness, and I loved it more than I can say.

“To know that I lived and walked the earth was a blow to his heart.” Next-level thumos!

“To know that I lived and walked the earth was a blow to his heart.” Next-level thumos!

When Gimli rebukes him for doing this—implying that it was ill-advised and beyond his capacity—Aragorn tells his friend, “You forget to whom you speak.” Incredible response, incredible man.

He has been waiting his whole life for this, and he is man enough for the great moment.

He has been waiting his whole life for this, and he is man enough for the great moment.

It's not simply bravado that prompts Aragorn (though that might not have been the worst thing either—moralistic scolds won't understand.) His decision has strategic effects. Panicked by the showdown, Sauron makes an unforced error shortly thereafter by attacking Gondor too soon.

What do Jackson and the screenwriters do with this absolutely crucial scene?

The theatrical cut deletes it altogether.

That’s pretty bad, but it gets worse...

The theatrical cut deletes it altogether.

That’s pretty bad, but it gets worse...

In an extended cut the scene is altered so that Sauron basically bitchslaps Aragorn with a vision of Arwen suffering—which causes him to stagger back and drop the Stone of Orthanc in defeat.

Cmon! Like I said, Jackson and his team are owed a debt of gratitude for brining LotR to the screen as well as they did. But these changes are so incredibly unnecessary—demoralizing even.

We don’t need to see emo-Aragorn second-guessing himself like some contemporary democratic soul. We need to see the Aragorn who "wrenches the Stone to his will."

Tolkien's hero is magnanimous to the bone, and this is the virtue we most need to rediscover right now, with so much of modern life being specifically designed to demean and discourage us.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh