By the Spring of 2021, the early VOCs had largely run their course and it seemed like the pandemic might soon be over. But then a new variant of concern entered the scene: B.1.617.2 (Delta).

25/

25/

Delta was not particularly immune evasive, but it was fast. Notably, it had the strongest predicted FCS of any variants to date changing 681P to 681R.

26/

26/

Delta became dominant like no other variant had accomplished previously. It was basically the only lineage in circulation. Many experts believed that all future lineages would be Delta-derived.

27/

27/

Delta spun off lots of offspring. Delta (B.1.617.2) already had 3 numbers, so all of its offspring got the next available letter: AY.

However, none of the AYs were much better than the others, so we just kept getting more AYs. They made it all the way to AY.134.

28/

However, none of the AYs were much better than the others, so we just kept getting more AYs. They made it all the way to AY.134.

28/

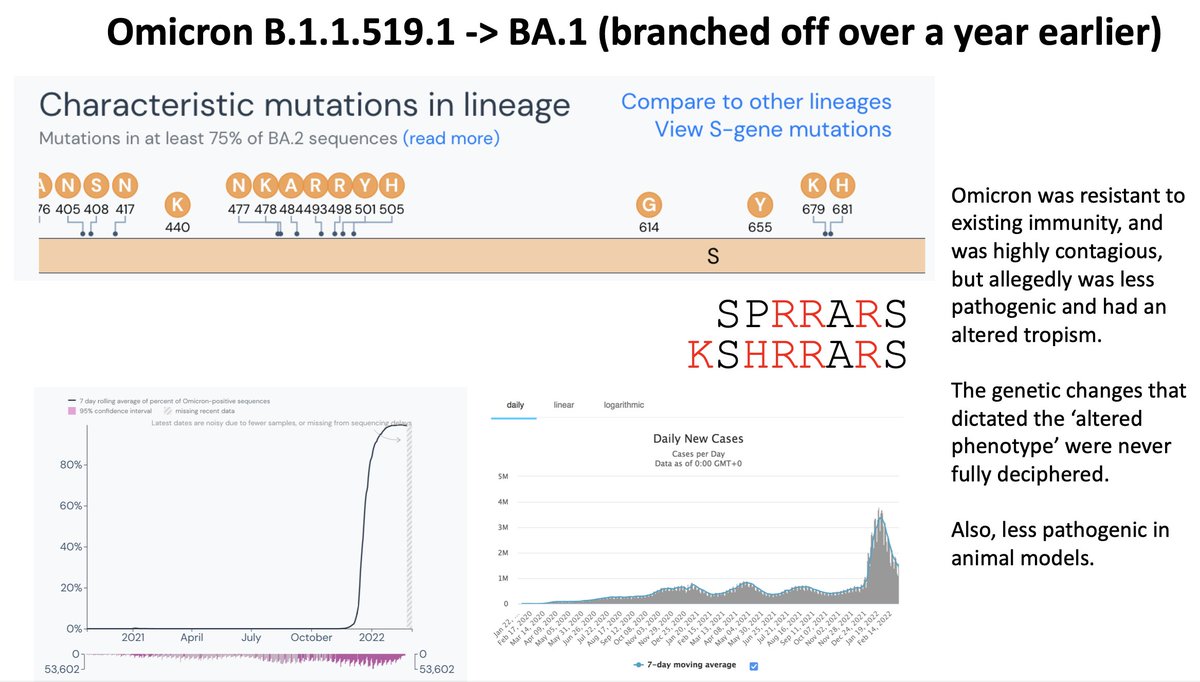

Then in November of 2021 we learned about a new VOC circulating in South Africa that had a ton of changes, many of which were immune evading changes.

29/

29/

A word about antibodies and escape mutations.

Antibodies are defensive proteins we generate that bind to things we want to get rid of.

If an antibody can inactivate a virus simply by binding it, it is called a neutralizing antibody.

30/

Antibodies are defensive proteins we generate that bind to things we want to get rid of.

If an antibody can inactivate a virus simply by binding it, it is called a neutralizing antibody.

30/

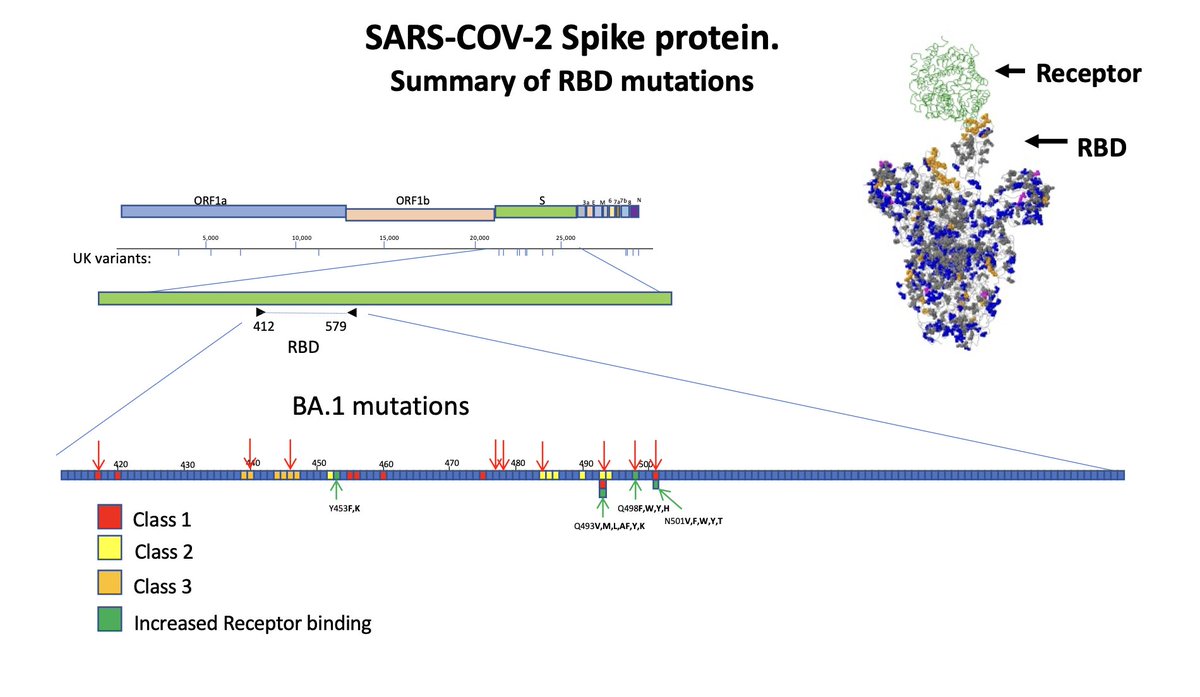

Not all antibodies that bind Spike are neutralizing. The vast majority (~90%) of the ones that neutralize do so by binding the receptor binding domain (RBD) of Spike.

31/

31/

If the virus acquires a mutation that prevents a neutralizing antibody from binding/neutralizing, it is called an ‘escape mutation’.

32/

32/

There are 3 main ‘classes’ of RBD neutralizing antibodies, and each classes has defined escape positions. Thanks to the work of @jbloom_lab @yunlong_cao and many others, we have a pretty good idea of which single mutations are escape mutations, and Omicron had a ton of them.

33/

33/

At this point in time (early 2022) the immunity against SARS-CoV-2 was relatively ‘homogeneous’. We had generally all been vaccinated or infected with roughly the same virus. This made it a bit ‘easier’ for a lineage like Omicron to be widely successful.

34/

34/

From the beginning there were 2 lineages of Omicron (B.1.1.519): BA.1 and BA.2. The two were very different, but clearly of a common ancestor.

35/

35/

I am personally convinced that they both came from the same persistent infection (which had lasted over a year). We know from our studies with persistent infections and cryptic lineages that individuals with persistent infections can carry a vast diversity of lineages.

36/

36/

BA.1 swept first in most places, but BA.2 had more staying power. BA.1 probably caused more infections than any other lineage ever, but only lasted about 6 months and it spun off no major offspring.

37/

37/

BA.2 initially caused fewer infections than BA.1, but it had stronger offspring: BA.2.12.1, BA.2.75, CH, and eventually BA.2.86/JN.1.

38/

38/

Next after BA.2 was BA.4 and 5. No one really knows where these came from. BA.4 and 5 were VERY closely related, and very clearly close relatives of BA.2, but not clear descendants. They were probably recombinants, but it’s never REALLY been sorted out as far as I know.

39/

39/

It was during this Omicron period when lineages became a variant soup of convergent changes. Patients still had a few antibodies that would neutralize the virus, so all different lineages started picking up the same mutations to evade them.

40/

40/

I started making these graphs to try to keep up with the convergence, but I couldn’t keep up with it. @dfocosi has done a much better job at keeping these updated.

41/

41/

Circulating lineages were mostly BA.4/5 descendants through the end of 2022, but a few BA.2 descendants kept hanging on.

Eventually two different BA.2 lineages recombined to make a pretty fit lineage called XBB.

42/

Eventually two different BA.2 lineages recombined to make a pretty fit lineage called XBB.

42/

XBB wasn’t really able to outcompete the BA.4/5 descendants until its kids found a key change: S:486P. This happened many times: XBB.1.5, XBB.1.9, XBB.1.16, etc.

Many of these lineages (and their descendants like EG.5 and HV.1) are still circulating today.

43/

Many of these lineages (and their descendants like EG.5 and HV.1) are still circulating today.

43/

This summer we got our latest curveball (BA.2.86). This lineage appeared in Israel and was clearly derived from something that circulated over a year ago.

44/

44/

Personally, I first thought this was just a persistent infection that @shay_fleishon had found. @LongDesertTrain has found scores of these occurrences.

However, within a week the same exact lineage had appeared on three different continents.

It was concerning.

45/

However, within a week the same exact lineage had appeared on three different continents.

It was concerning.

45/

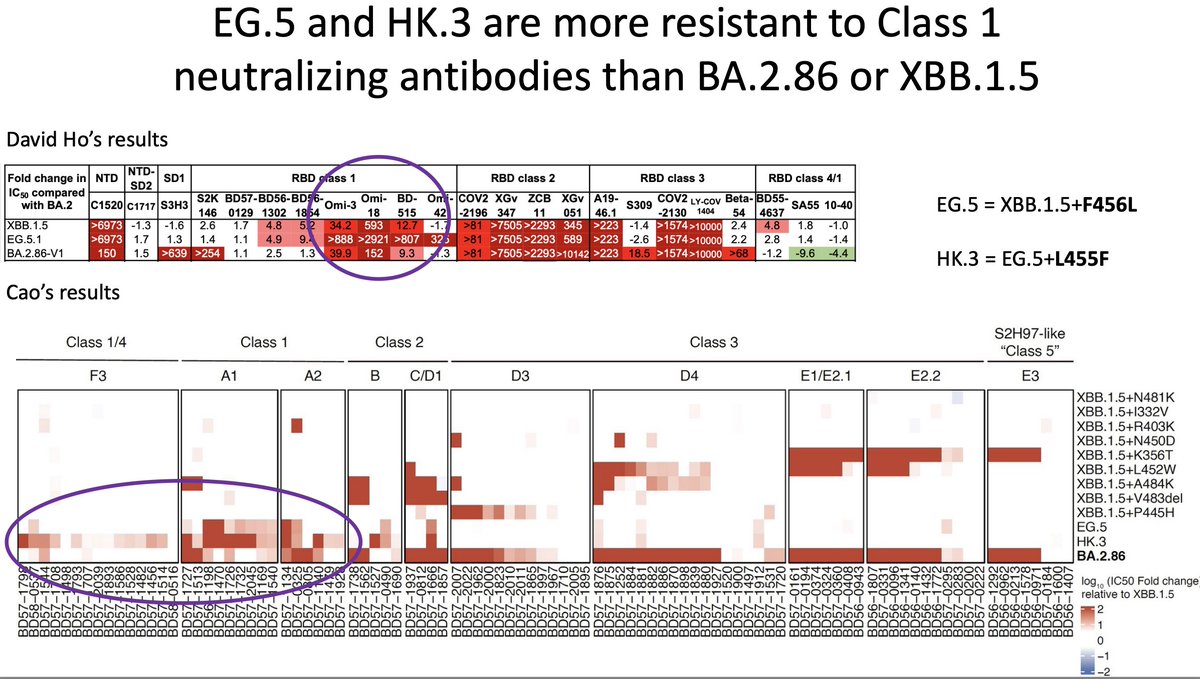

BA.2.86 did not initially take off like an Omicron. They found that it wasn’t really any more immune evasive than the contemporary lineages like EG.5 or HK.3.

46/

46/

In fact, it was clear that BA.2.86 was still sensitive to some class 1 antibodies that EG.5 and HK.3 were resistant to. It was also clear that they were resistant was because of the mutations F456L and L455F.

47/

47/

I was expecting the next step would be for BA.2.86 to pick up one of these.

I was close, it picked up L455S, which created JN.1

48/

I was close, it picked up L455S, which created JN.1

48/

Continued in a 3rd thread.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh