Something’s happening here: BA.2.86 and the furin cleavage site (FCS)

The FCS has been highly conserved in all SARS-CoV-2 lineages. Why is it disappearing so much more frequently in BA.2.86/JN.1? 1/16

The FCS has been highly conserved in all SARS-CoV-2 lineages. Why is it disappearing so much more frequently in BA.2.86/JN.1? 1/16

The FCS, located around S:681-685, is one of the most distinctive features of SARS-CoV-2. Its presence causes the spike to be cleaved within the cell by furin, priming it for membrane fusion & cell entry (which requires a 2nd spike cut by TMPRSS2). 2/16

Early studies showed the FCS to be essential for SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung cells, and a study by @PeacockFlu showed that the FCS was required for transmission (in ferrets) & evaded host immune defenses. 3/16

The FCS is not only highly conserved but has been enhanced by P681H/P681R—which have been universal for nearly 3 years. Omicron added the FCS-adjacent S:N679K, but apart from that, even mutations in the surrounding region have been uncommon. 4/16

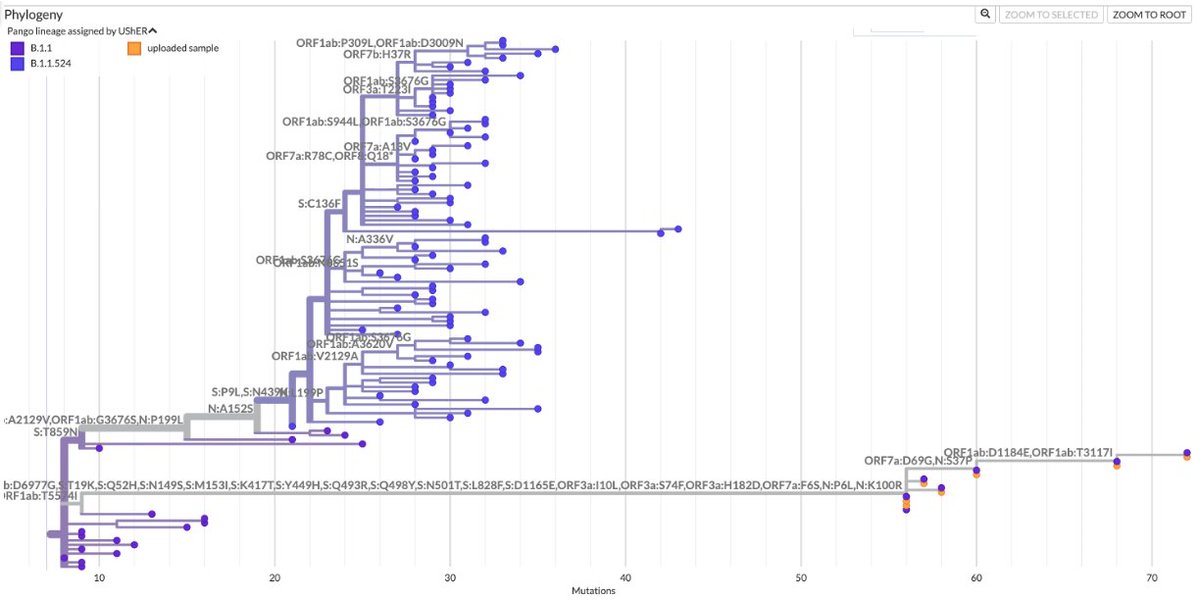

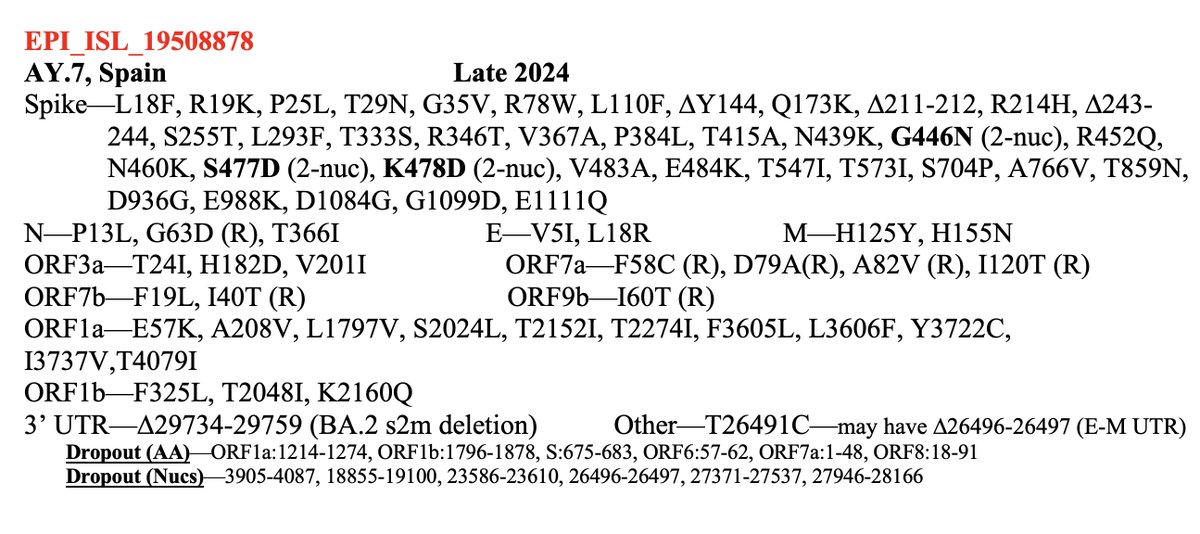

But in BA.2.86—mainly JN.1 (BA.2.86 + S:L455S = JN.1) as it’s the dominant form of BA.2.86—FCS-destroying mutations have arisen with remarkable frequency. To be clear, this is a tiny minority of all BA.2.86, but it’s a clear departure from previous trends. 5/16

The most common FCS-destroying mutation has been S:R683W, which has been in ~36 BA.2.86* sequences. These are very scattered, so they represent 20 or more independent acquisitions. The largest R683W cluster seems to be five sequences. 6/16

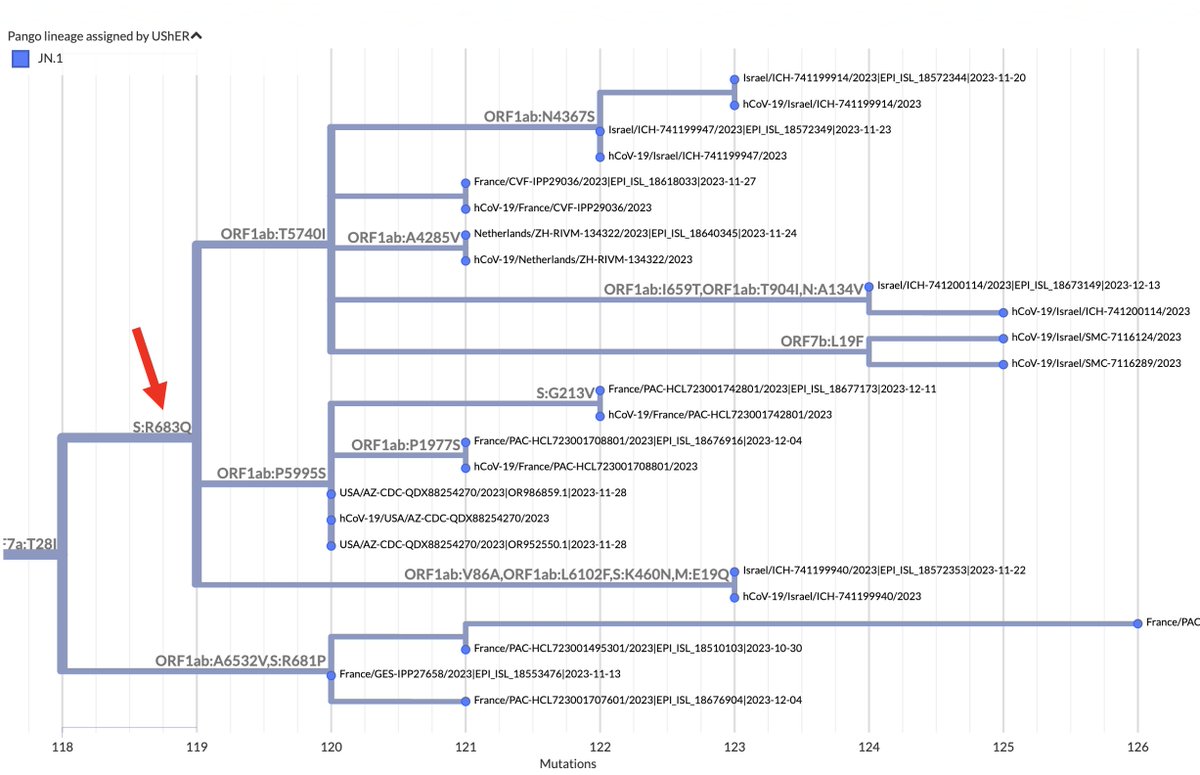

FCS-destroyer S:R683Q is less common, with 14 sequences, but 11 of those sequences belong to the same branch, which has spread across 5 countries and 3 continents. 7/16

Intriguingly, this branch is part of a larger (400-sequence) JN.1 branch with a 2-nucleotide mutation: ORF1b:V1271T (NSP13_V348T). Two-nucleotide mutations acquired in one leap are extremely rare, yet this one occurred in three different (small) XBB lineages in 2023. 8/16

Prior to 2023, ORF1b:V1271T was in just 25 sequences—one Delta, the rest BA.1/2/5. All acquired both nuc mutations in one jump. Only 278 sequences ever have had 1 of these 2 nuc mutations but not the other, a strong sign each individually is deleterious. 9/16

Curiously, there appears to be a 4-sequence branch just below the S:R683Q one (within the ORF1b:V1271T lineage) that has lost S:H681R through an S:R681P reversion. The furthest sequence on this branch seems to have acquired the extraordinarily rare S:P681S. 10/16

It’s not entirely clear of the four S:R681P sequences on the branch above are real or some sort of artifact, but the sequences look clean, come from 3 different originating labs and 2 different submitting labs, and fit the pattern of unusual FCS mutations in BA.2.86. 11/16

While the FCS-destroying R683W & R683Q are the most extreme examples, several other FCS or FCS-adjacent mutations have sprung up w/BA.2.86. S:K679M, for example, is in 22 BA.2.86, compared to 29 previous sequences ever (of which zero had S:681R). 12/16

More common have been mutations at the FCS-adjacent S:S680 in BA.2.86. S680F is the most frequent, but S680P and S680Y have also appeared numerous times. I do not know what effect this is expected to have on the FCS. 13/16

S:R681H reversions (which brings 681 back to the residue in almost all other Omicron lineages) have also been quite common. But there are so many contaminated sequences recently that deciphering exactly how common this reversion has been would require a lot of work. 14/16

There also seem to be an increase in mutations in various other FCS-region residues, but I don’t have the energy to do an analysis of that right now. I’m guessing lineage arch-guru @siamosolocani can speak to this though. 15/16

What is the meaning of it all? People probably get tired of me saying this, but I don’t know. S:681R is thought by most to increase FCS efficiency. Does this somehow reduce transmissibility in BA.2.86? Are FCS-loss mutations a kind of overcompensation? Thoughts welcome. 16/16

I like the idea of @PriscillaFalzi1—premature shedding of S1 (which makes cell attachment impossible) could explain this. This would also help explain the numerous apparent K679N & R681P reversions. As with NTD deletions, there's a stability tradeoff.

https://twitter.com/PriscillaFalzi1/status/1739450424627703855

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh