In the “Six Secret Teachings of Jiang Ziya” (one of the 7 Military Classics of ancient China) King Wu asks Jiang Ziya how others can assist the ruler in developing & implementing strategy. His answer is an interesting early conceptualization of the modern general staff system:

First is Fuxin (literally stomach and heart) An individual in charge of advising about secret plans for responding to sudden events; investigating Heaven so as to eliminate sudden change; exercising general supervision over all planning; and protecting the lives of the people.

Next five Planning Officers: A responsible for planning security and danger; anticipating the unforeseen; discussing performance and ability; making clear rewards and punishments; appointing officers; deciding the doubtful; and determining what is advisable and what is not.

Three Astrologers: responsible for the stars and calendar; observing the wind and qi, predicting auspicious days and times; investigating signs and phenomena; verifying disasters and abnormalities; and knowing Heaven's mind with regard to the moment for completion or abandonment.

Three Topographers: in charge of the army's disposition and strategic configuration of power when moving and stopped [and of] information on strategic advantages and disadvantages of land features so as not to lose the military benefit of the terrain.

Nine Strategists: : responsible for discussing divergent views; analyzing the probable success or failure of various operations; selecting the weapons and training men in their use; and identifying those who violate the ordinances.

Four Supply Officers: responsible for calculating the requirements for food and water; preparing the food stocks and supplies and transporting the provisions along the route; and supplying the five grains so as to ensure that the army will not suffer any hardship or shortage.

Four Officers for Flourishing Awesomeness: responsible for picking men of talent and strength; for discussing weapons and armor; for setting up attacks that race like the wind and strike like thunder so that [the enemy] does not know where they come from.

Three Secret Signals officers: responsible for the pennants and drums, for clearly signaling to the eyes and ears; for creating deceptive signs and seals and issuing false designations and orders; and for stealthily and hastily moving back and forth, going in and out like spirits

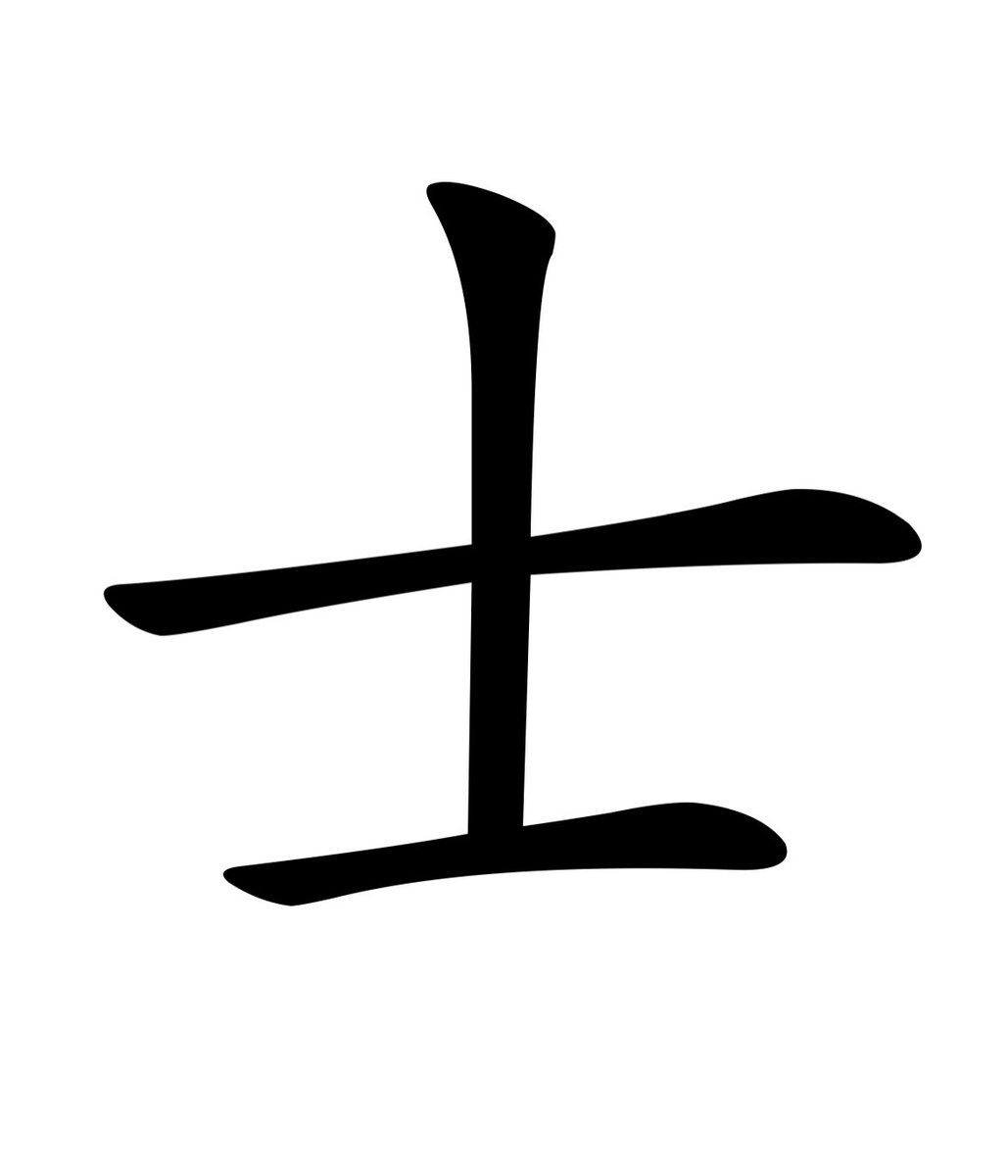

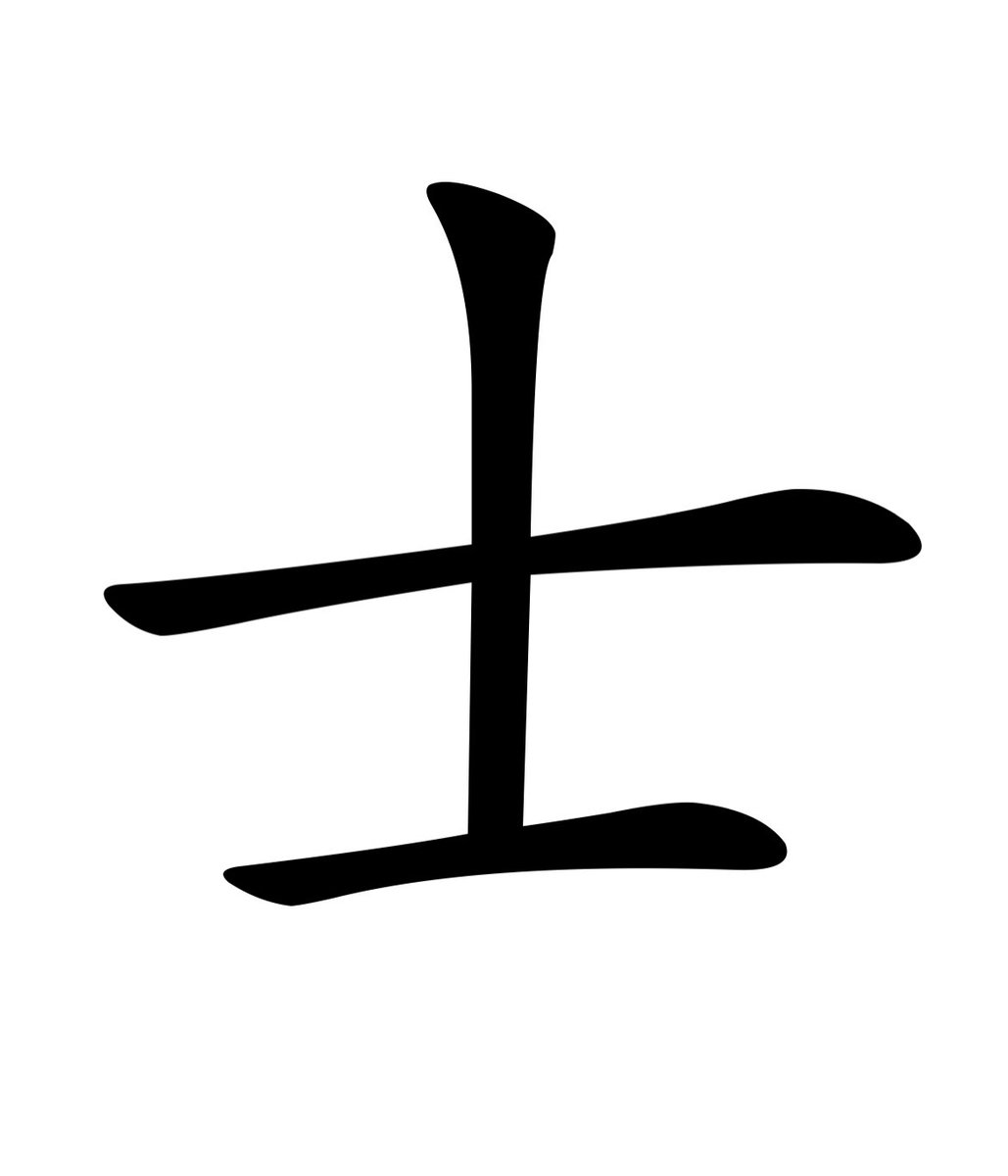

Four “Legs and Arms”: responsible for undertaking heavy duties and handling difficult tasks; for the repair and maintenance of ditches and moats; and for keeping the walls and ramparts in repair in order to defend against and repel [the enemy].

Two Liaison officers: responsible for gathering what has been lost and supplementing what is in error; receiving honored guests; holding discussions and talks; mitigating disasters; and resolving difficulties.

Three Officers of Authority: responsible for implementing the unorthodox and deceptive; for establishing the different and the unusual, things that people do not recognize; and for putting into effect inexhaustible transformations.

Seven “Ears and Eyes”: responsible for going about everywhere, listening to what people are saying; seeing the changes; and observing the officers in all four directions and the army's true situation.

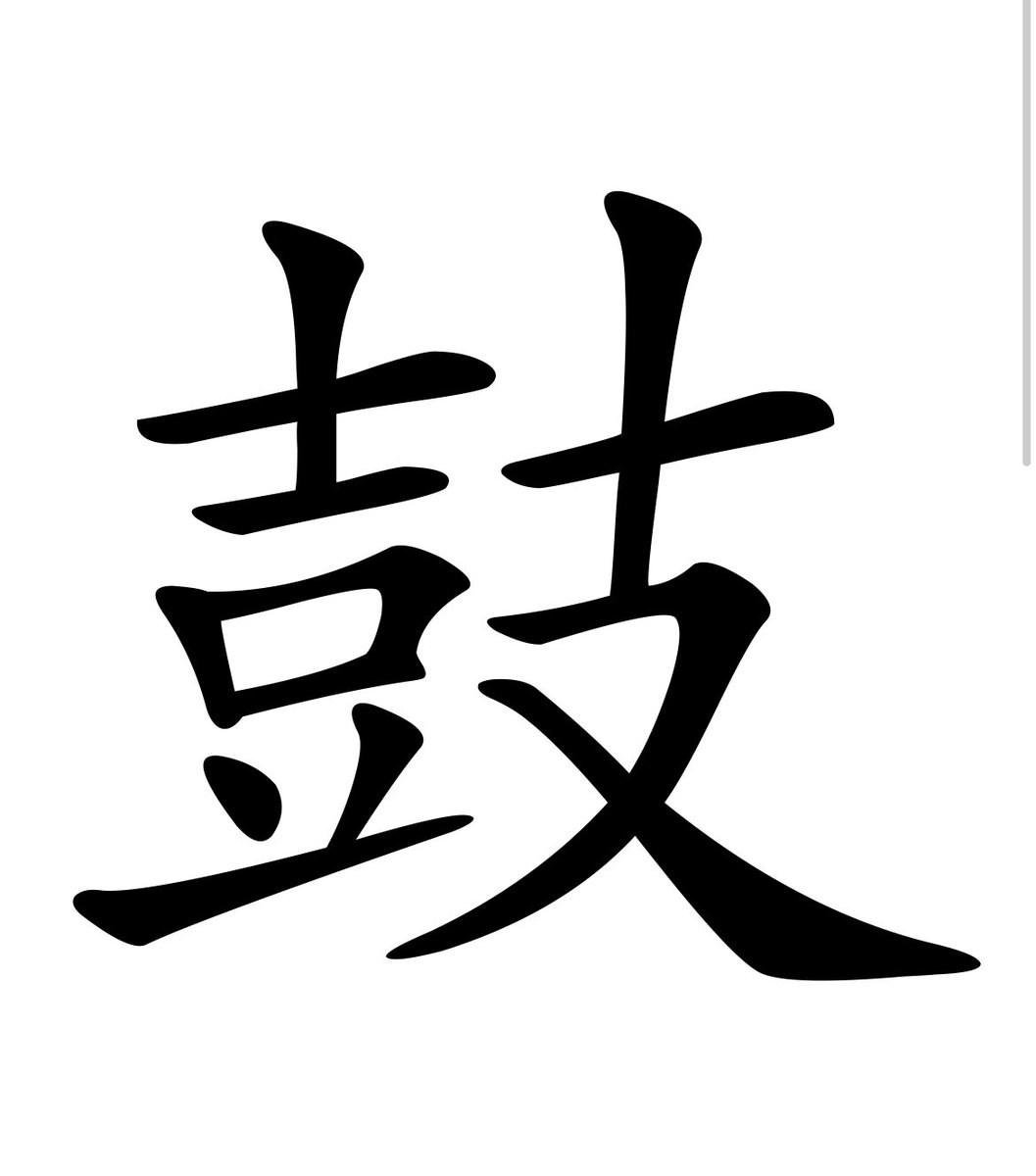

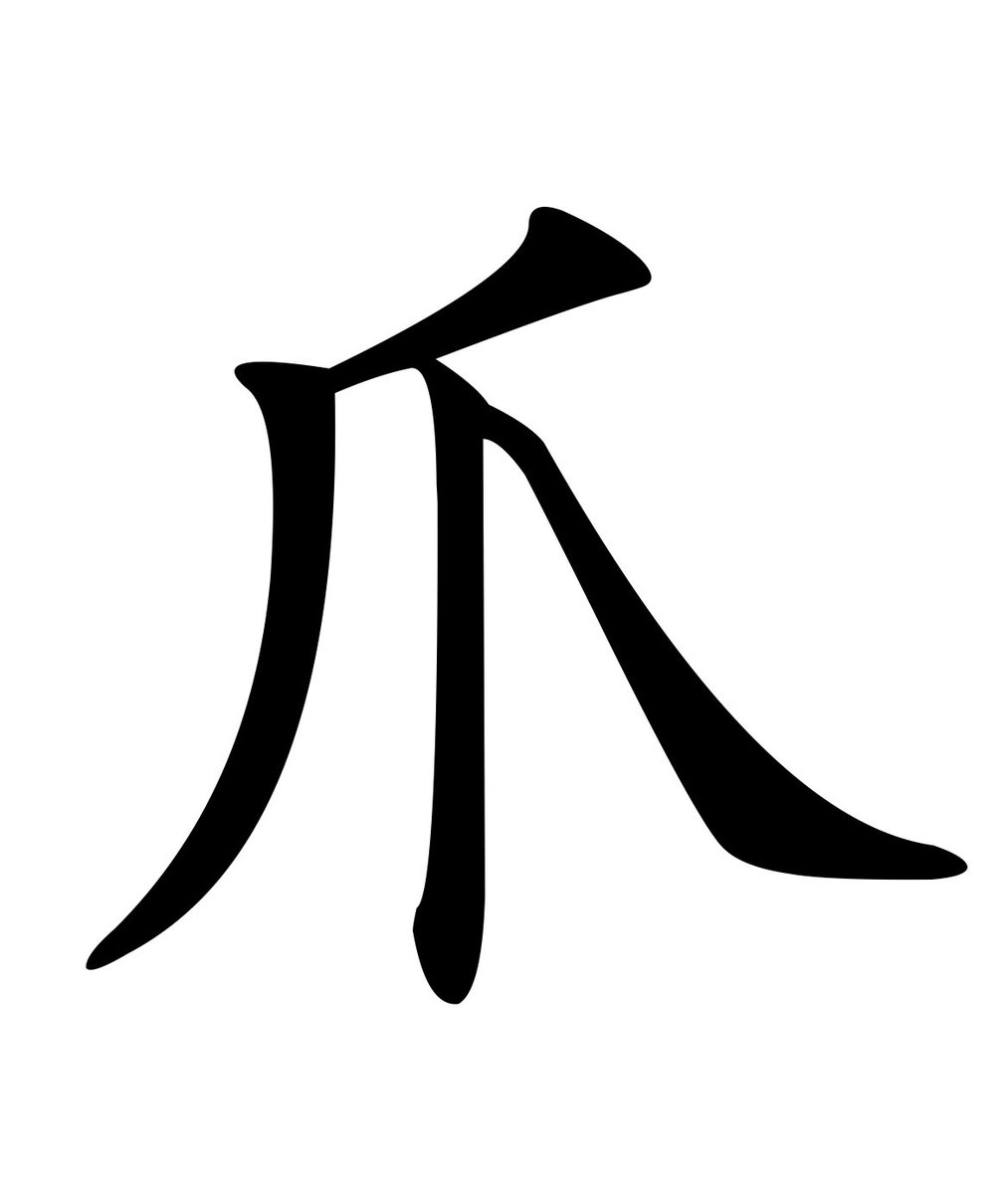

Five “Claws and Teeth”: responsible for raising awesomeness and martial [spirit]; for stimulating and encouraging the Three Armies, causing them to risk hardship and attack the enemy's elite troops without ever having any doubts or second thoughts.

Four “Feathers and Wings”: responsible for flourishing the name and fame [of the army]; for shaking distant lands [with its image]; and for moving all within the four borders in order to weaken the enemy's spirit.

Eight Roving Officers: responsible for spying on [the enemy's] licentiousness and observing their changes; manipulating their emotions; and observing the enemy's thoughts in order to act as spies.

Two Officers of Techniques: responsible for spreading slander and falsehoods and for calling on ghosts and spirits in order to confuse the minds of the populace.

Three Officers of Prescriptions: in charge of the hundred medicines; managing blade wounds; and curing the various maladies.

Two Accountants: responsible for accounting for the provisions and foodstuffs within the Three Armies’ encampments and ramparts; for the fiscal materials employed; and for receipts and disbursements.

So next time you are in a joint HQ, attempt to determine who are the modern equivalents of “Claws and Teeth, “Eyes and Ears” or “Officers for Flourishing Awesomeness,” and ponder whether or not the ancient equivalent to DTS (“Accountants”) was any less capricious and infuriating.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh