A lot of people confuse fast fashion with cheap clothing. It's true that fast fashion is cheap, but not all cheap clothing is fast fashion. The two terms are not synonymous. Fast fashion is a very distinctive thing. 🧵

Let's start at the beginning. Before the mid-19th century, most clothing was made by women in the home or by a tailor. Ready-made clothing was largely limited to cheap workwear, such as what would have been worn by slaves, miners, and sailors.

In 1849, Brooks Brothers invented the first ready-made suit. Soon after, they also produced ready-made uniforms for both sides of the American Civil War. In the early days of ready-made manufacturing, clothing quality was quite poor, esp when compared to tailor-made clothes

In fact, Brooks Brothers ran into trouble when their military uniforms fell apart in the rain. Facing a shortage of wool, the uniforms were made from shredded bits of decaying rags, sawdust, and glue, which were pressed into a semblance of cloth. US gov took them to court later.

Over time, ready-made manufacturing improved. The first big jump came when the US military gave factories their data on the measurements of enlisted soldiers (chest size, neck size, arm length, etc). This is how they made clothes that mostly fit the average person.

I will spare you the details of how various technologies improved, such as how pad stitching, traditionally done by hand, was eventually done with a single thread rollpadding machine, saving hours from production time. Video below shows how it's done at some factories now.

Suffice it to say that clothing production went from being one item made for a specific person to multiple garments made for the masses.

This created a new business model. For much of the 20th century, clothing production went like this:

This created a new business model. For much of the 20th century, clothing production went like this:

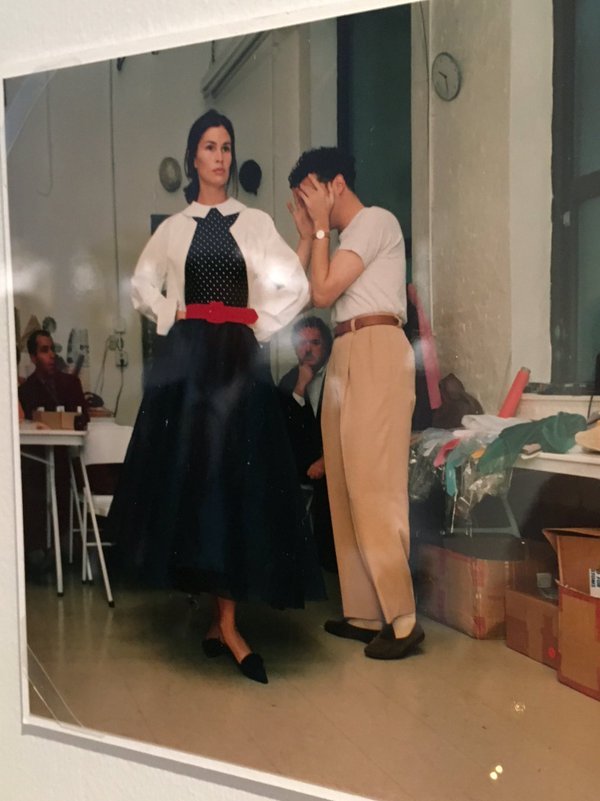

A designer would come up with an idea, create samples, take those samples to a trade show, and show the collection to store buyers, who would then place orders. These orders would go into production and, about six months later, show up in stores. That's when you see them.

Then something happened in the 1980s. Faced with stiff competition and cheap imports, US companies developed something called the "quick response system." In this new model, a store would only stock a limited number of items in each clothing style.

If those items did well during the season, they would quickly restock. This is different from the old system, where you went to a tradeshow, bought a bunch of stuff, and then sold them six months later. You kept tighter reins on inventory supply & manufacturing.

So instead of ordering 100 blue shirts and 100 red shirts, and then selling through, you might only order 50 blue shirts and 50 red shirts. If blue shirts do well that season, you quickly re-up. This limits your risk and allows you to quickly respond to demand.

This shift requires digital technology, new inventory systems, and tighter control over the manufacturing supply chain. The system was later perfected by companies like Zara and H&M.

This is the start of fast fashion. Fast fashion is about quickly responding to trends in the market and meeting demand with cheap clothing. It requires very specific inventory and supply chain management systems.

Remember, in the old system, a designer might debut a look on the runway, and it shows up in stores about 8 months later. In the new system, a fast fashion brand looks at the runway, copies the look, and it's in stores maybe a week later—before even the designer's collection.

The lack of thought in design and the rapidity of production allow these companies to drop many more collections. Designers typically do 2-5 collections per year. H&M does 16. Zara does 24. Shein has new drops hourly. The sheer number of options at these stores is staggering.

The real problem with fast fashion is that it speeds up the trend cycle. Oh, fleece and motorcycle jackets are trending? Mash them together and sell fleece moto jackets. The sudden ubiquity of these designs means they become "burnt," and no one wants to wear them anymore.

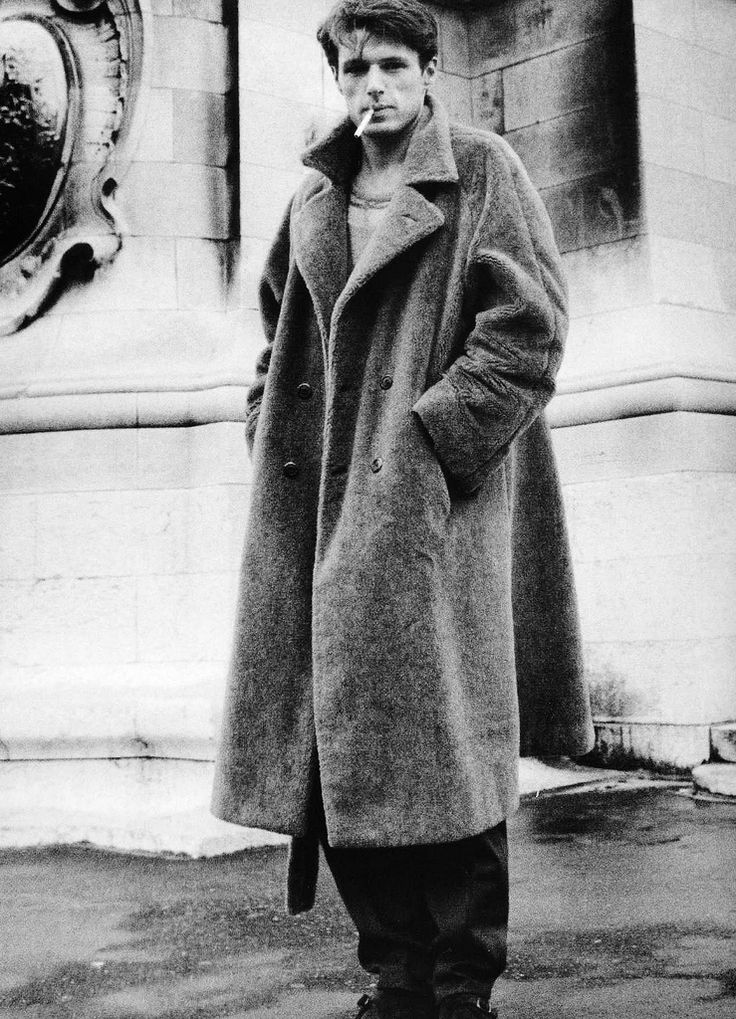

The rapidity of fashion is certainly not limited to fast fashion. When he left Dior, Raf Simons complained that fashion moved from doing 2 shows per year to 6 shows (spring/ summer, fall/winter, mid-seasons, pre-seasons, and resort). This leaves no time for the creative process.

But fast fashion has sped this up to a breakneck pace. Online content creators encourage huge shopping hauls. Many run out of things to say. Hungry for new content, they talk about quickly evaporating trends.

Fast fashion works in this entire ecosystem where consumers with limited budgets are trying to keep up with rapidly vanishing trends, so they buy new stuff that they wear once, sometimes not even at all, before throwing stuff away. The result is an ecological disaster.

This system puts a strain on workers who have to produce cheap, trendy clothing. Last month, I interviewed one of these workers. She makes $50 for a 12-hour shift. She shares a 2 bedroom room apartment with 6 other ppl. She sleeps in the kitchen.

thenation.com/article/archiv…

thenation.com/article/archiv…

There are certainly problems with cheap clothing. Workers involved are often not making enough to live. But fast fashion is a distinct sub-category of cheap clothing. It's about bringing the hottest, trendiest looks as quickly as possible. Hence the term "fast fashion."

There are a lot of cheap brands that are not fast fashion. Hanes, Dickies, Carhartt, Camber, Lands' End, Vans, Wrangler, Lee, and Clarks are not about bringing the hottest trends off the runway to the store ASAP. I would include The Gap, Old Navy, and Uniqlo in that.

One can quibble. Uniqlo has collaborated with Lemaire, Jil Sander, and Engineered Garments; The Gap famously collaborated with Kanye and Balenciaga. These are designer-ish looks for less money. But I think this is still different from what Shein is doing.

Mostly, I think a lot of people online conflate "cheap clothing" with "fast fashion," and don't make some important distinctions. IMO, fast fashion is a unique system that should be couched in the context of the evolution of fashion production.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh