Ten cognitive check points (general rules or heuristics to help guide my practice) I use in the ICU to help make sure I don't get too far off track. A thread🧵👇

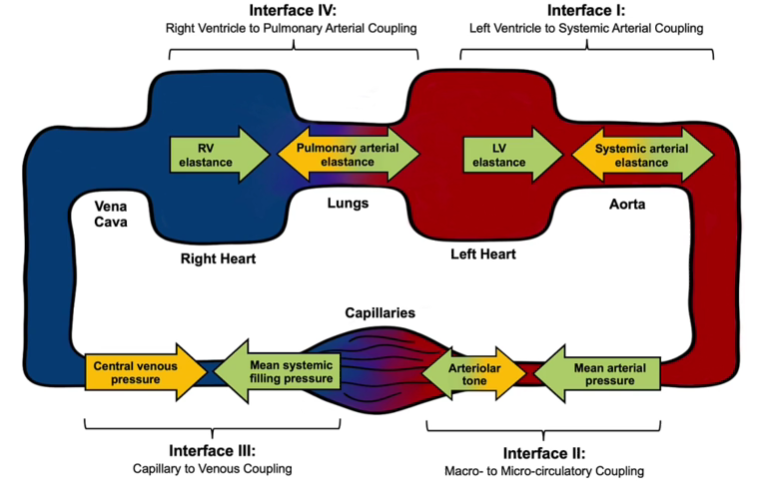

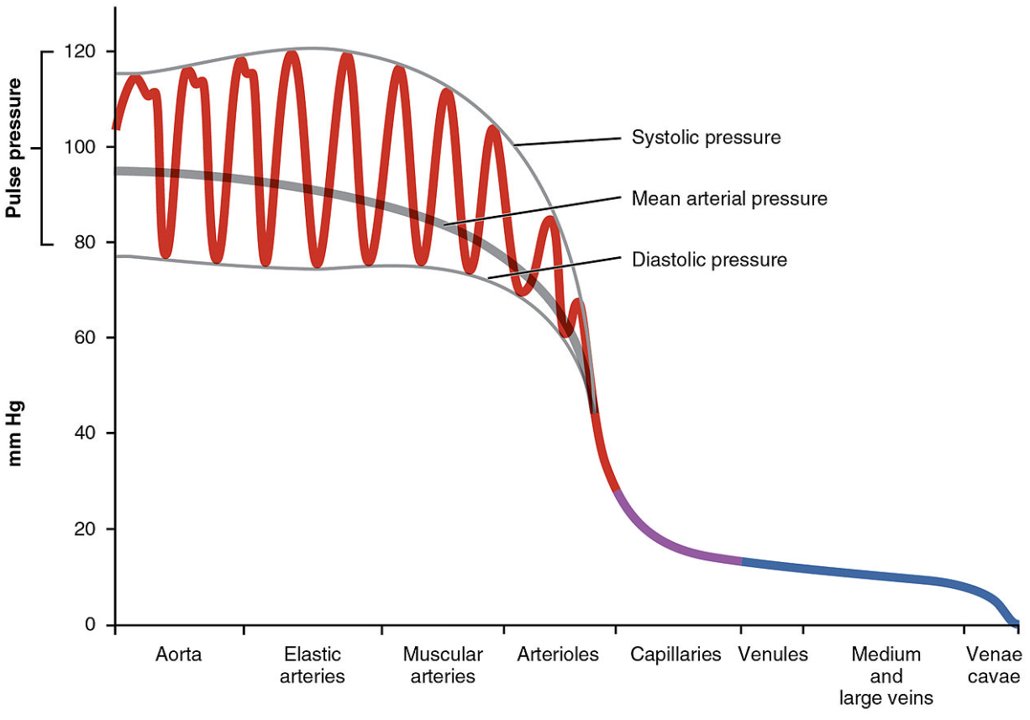

1/10: Shock with a narrow pulse pressure (<30mmHg) needs an urgent #POCUS (or echo) to identify occult RV/LV failure, obstructive shock, or severe hypovolemia.

#medtwitter #foamed #echofirst #pocus #MedEd #medicine #FOAMcc

1/10: Shock with a narrow pulse pressure (<30mmHg) needs an urgent #POCUS (or echo) to identify occult RV/LV failure, obstructive shock, or severe hypovolemia.

#medtwitter #foamed #echofirst #pocus #MedEd #medicine #FOAMcc

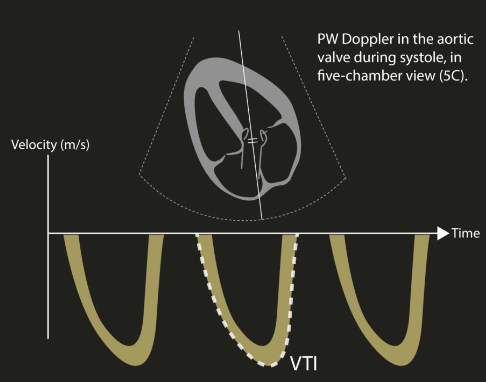

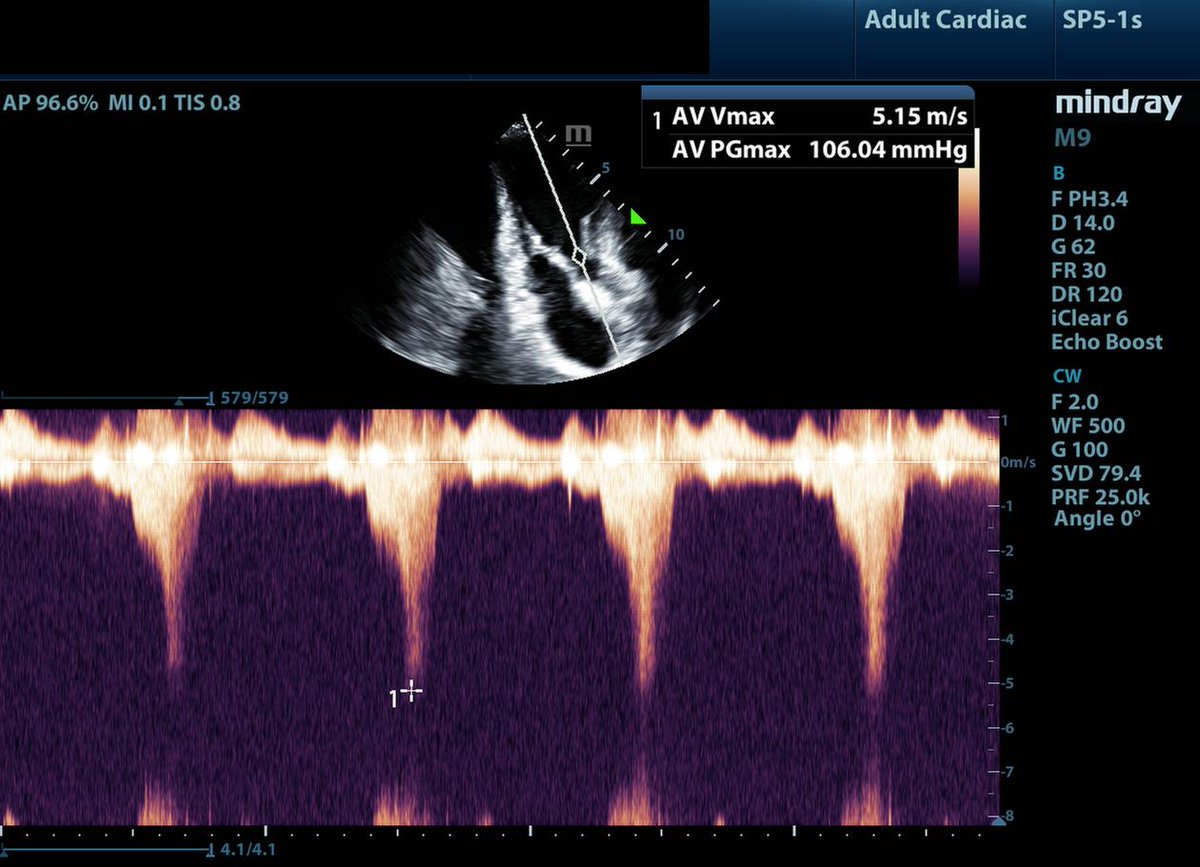

2/10: When you see a pt. who is "persistently hypovolemic" that transiently responds to fluid loading. First, ensure not bleeding.🩸 Second, instead of assuming they are just really dry, think about dynamic LVOTo, intracavitary gradients, or diastolic dysfunction. Giving them 15L of fluid to treat persistent fluid responsiveness is likely not the right move.

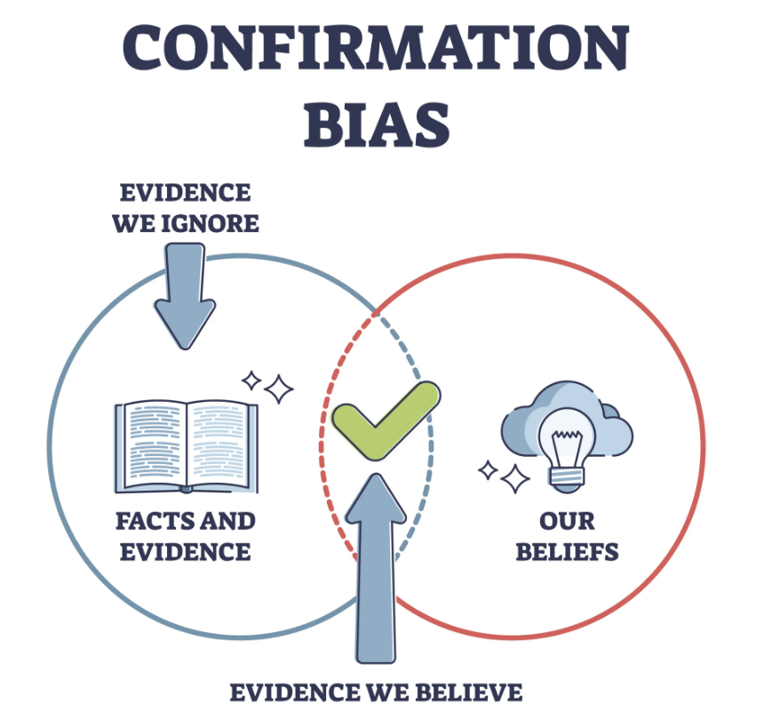

3/10: If a nurse (or anyone!) asks you the same question twice (e.g. should we consider getting a CT scan) don't take it that your judgement is being question - this is often a great indicator they have a different mental model about your pt. Explore the why and challenge your own assumptions.

4/10: The diagnosis of "septic shock" does mean the patient has distributive shock. 🫀❌ Even if it is pure septic shock, patients may have any phenotype of shock depending on their chronic comorbidities, acute cardiomyopathy, or secondary processes (core pulmonale, pericardial effusions etc.)

5/10: A persistently elevated lactate in a septic pt does NOT mean they are under-resuscitated or "dry" Step 1) do you have source control Step 2) Are you treating the right phenotype of shock? Step 3) Can we optimize real-time markers of perfusion (e.g. cap refill time) through volume, inotropes, MAP challenge, inodilators etc.

6/10: Be wary of admitting a patient to the ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis NYD (not yet diagnosed)- in the ICU, we should be able to figure out the D (diagnosis). Repeat the primary history, re-examine, consider pan-CT, echo, focused TEE etc. Think about where infection can hide! (valves, belly, heart etc.)

7/10: There is no such thing as a 'stable' post cardiac arrest patient. They just died. They are by definition the patient closest to death in your department/hospital. The disease that caused them to die is still at play, time matters! 🫀⌛️Prioritize diagnosis, ensuring adequate access (Art + venous), and definitive treatment.

8/10: Post cardiac arrest pts. are simultaneously a 1) cardiac patient (their heart stopped) 2) neuro patient (we care about their brain) 3) and trauma patient (someone just crushed their chest for like 30 min).

If you are CT scanning post arrest, low threshold to PAN scan (head, chest, abdo)

Also, if you are going to order a CT chest, consider a PE protocol so you never have to discuss on rounds whether the patient could have an occult PE as the etiology arrest!!! 🫀🧠🦴

If you are CT scanning post arrest, low threshold to PAN scan (head, chest, abdo)

Also, if you are going to order a CT chest, consider a PE protocol so you never have to discuss on rounds whether the patient could have an occult PE as the etiology arrest!!! 🫀🧠🦴

10/10: If a pt or family says they want everything done - clarify this!!!

When you dive into it, it often means not giving up on them. They want you to try to diagnosis them, correct treatable causes, and if they are dying, provide them a comfortable and dignified death.

Rarely is it life at all cost or indefinite prolongation of dying with life support.

When you dive into it, it often means not giving up on them. They want you to try to diagnosis them, correct treatable causes, and if they are dying, provide them a comfortable and dignified death.

Rarely is it life at all cost or indefinite prolongation of dying with life support.

These are just a few observations from a very early career intensivist! Would love to hear everyone else's heuristics they use in their practice. @emily_fri @nickmmark @emcrit @PulmCrit @iceman_ex @IM_Crit_ @ThinkingCC @AndromedaShock @ChrisCarrollMD @precordialthump @Wilkinsonjonny @jon_silversides @Bram_Rochwerg @KimLewisMD

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh