Intensivist ⚕️ POCUS | Hemodynamics | Innovation

Co-founder of https://t.co/A68FZcHc6b -AI research assistant

Hemodynamic Calculators: https://t.co/3MMlpWXhRM

4 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

Episode 1: Myth: Volume Status is a single clinical entity.

Episode 1: Myth: Volume Status is a single clinical entity.

(2/x) Shock is inadequate tissue perfusion (think end organs).

(2/x) Shock is inadequate tissue perfusion (think end organs).

(2/x) Tip: Goal of diuresis is not just to produce lots of urine... its to produce lots of salty (high Na) urine.

(2/x) Tip: Goal of diuresis is not just to produce lots of urine... its to produce lots of salty (high Na) urine.

(2/x) For context, AS-2 was a 1500 patient RCT of a 6 hour resuscitation window compared to standard care in septic shock.

(2/x) For context, AS-2 was a 1500 patient RCT of a 6 hour resuscitation window compared to standard care in septic shock.

(2/x) At the core of AS2 is the concept of ‘microcirculation’ or that hemodynamic interventions we perform should improve tissue level perfusion.

(2/x) At the core of AS2 is the concept of ‘microcirculation’ or that hemodynamic interventions we perform should improve tissue level perfusion.

(2/9) Learn from your patients

(2/9) Learn from your patients

(1/x) I start with a scene survey.

(1/x) I start with a scene survey.

(1/x) Deeming a patient impossible to wean should only be done by groups of clinicians with extensive experience in this.

(1/x) Deeming a patient impossible to wean should only be done by groups of clinicians with extensive experience in this.

Tip 1: Just go see the patient.

Tip 1: Just go see the patient.

(1/x) If you missed the webinar, check it out here 👇- it is one of our best.

(1/x) If you missed the webinar, check it out here 👇- it is one of our best.

(2/x) In medical school, septic shock is described as a distributive shock where patients have hyperdynamic circulation with bounding pulses and warm extremities.

(2/x) In medical school, septic shock is described as a distributive shock where patients have hyperdynamic circulation with bounding pulses and warm extremities.

(1/5) Cognitive Trap: Search Satisficing Bias.

(1/5) Cognitive Trap: Search Satisficing Bias.

https://twitter.com/ross_prager/status/1935671737485504561(2/x) Of course, fluids may be beneficial in sepsis for some patients! However, this requires a few things to be true.

(2/x) Don't yell 'everyone who doesn't need to be here leave'.

(2/x) Don't yell 'everyone who doesn't need to be here leave'.

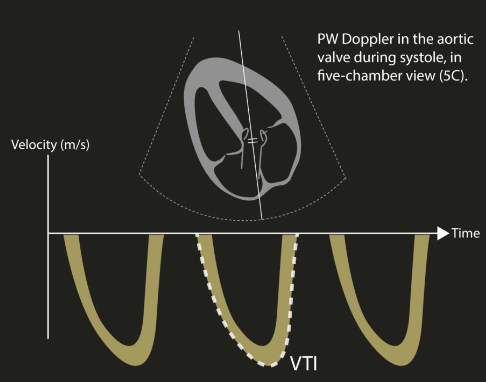

(2/x) The reason why clinicians feel for the pulse makes sense - we want our CPR to be generating enough stroke volume to create a palpable pulse.

(2/x) The reason why clinicians feel for the pulse makes sense - we want our CPR to be generating enough stroke volume to create a palpable pulse.

(1/5) Start by assessing the microcirculation (and its surrogates) to determine how severely end organs are impacted. This should help guide how aggressive you are at its management.

(1/5) Start by assessing the microcirculation (and its surrogates) to determine how severely end organs are impacted. This should help guide how aggressive you are at its management.

(1/10) Patients don't care how much you know, but rather, how you make them feel.

(1/10) Patients don't care how much you know, but rather, how you make them feel.

(2/x) Who’s being sued?

(2/x) Who’s being sued?

(2/x) To start, if a non-invasive ventilation (NIV) mask has a good seal, there are really only two key differences between invasive and non-invasive ventilation

(2/x) To start, if a non-invasive ventilation (NIV) mask has a good seal, there are really only two key differences between invasive and non-invasive ventilation

(2/x) A systematic review with meta-analysis of RCTs by Liu et al. 2021 in Critical Care Medicine demonstrated ....

(2/x) A systematic review with meta-analysis of RCTs by Liu et al. 2021 in Critical Care Medicine demonstrated ....