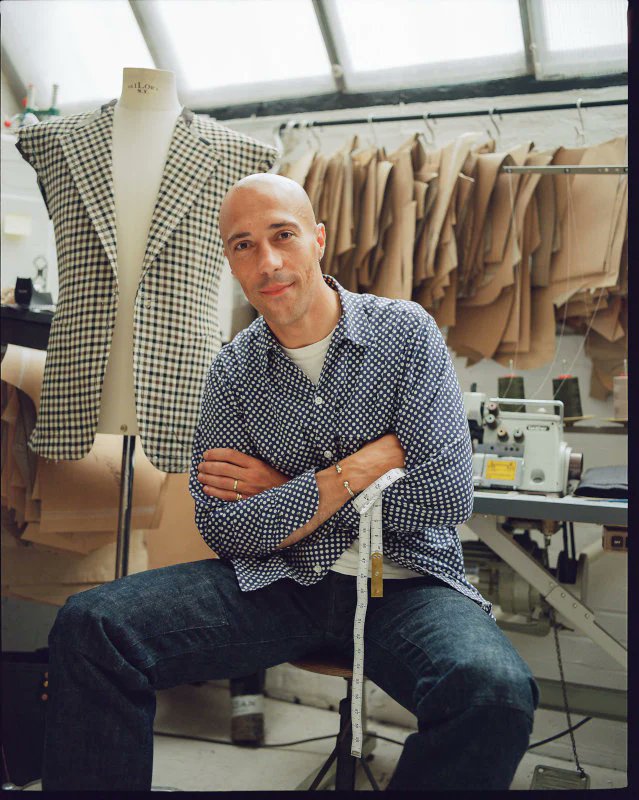

One of my tailors, Fred Nieddu, made all of the menswear for The Crown, including everything from the suits to sportswear. The clothes were surprisingly accurate in some ways but also deviated in others. Let's talk about those subtle details. 🧵

https://twitter.com/Ysasmendi/status/1741944542981423355

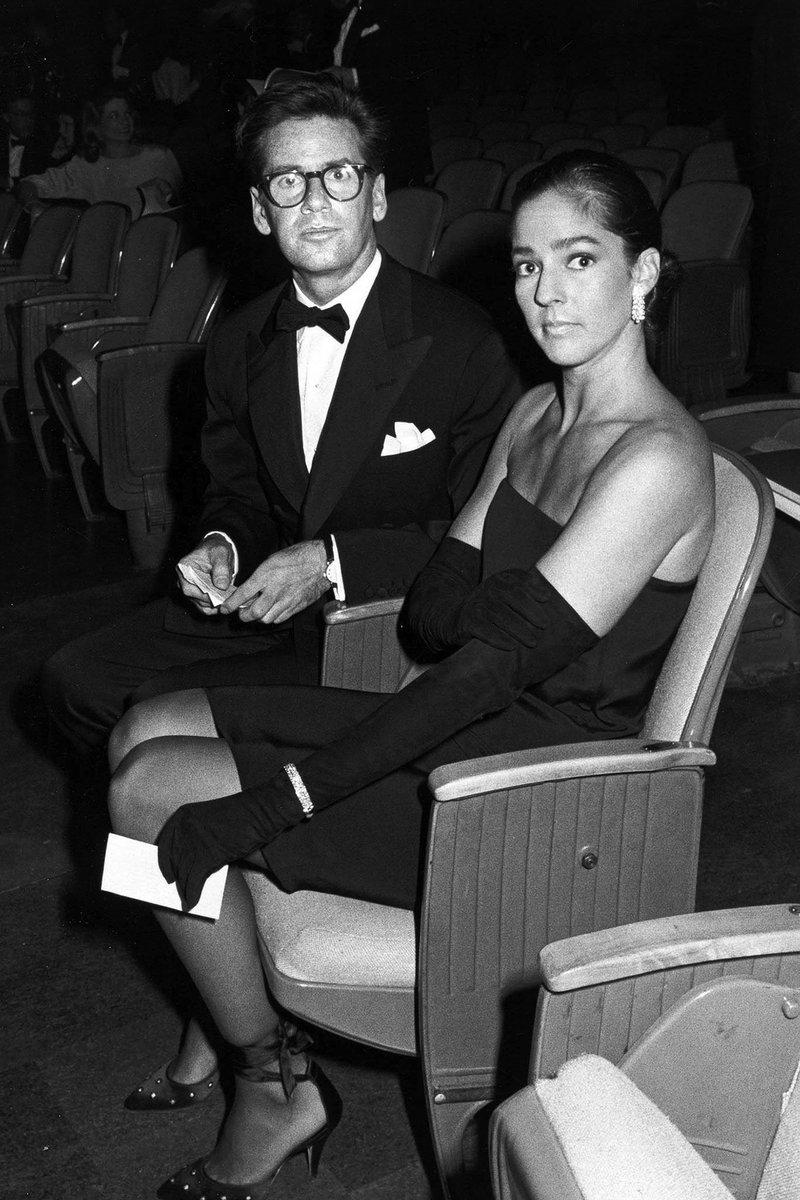

Like many young men, King Charles was influenced by the fashion of his day and only found his style later in life. In the 1960s, he wore single-breasted suits and sport coats with razor-thin lapels. Narrow lapels during this time were considered very "modern" (think: Mad Men).

Again, influenced by the fashion of his day, Charles switched to a wider lapel in the 1970s but still stuck with a single-breasted closure. Note how, in the '60s, his lapel ended about 1/3rd way from collar to shoulder seam. Below, it's closer to 1/2 (a more classic width)

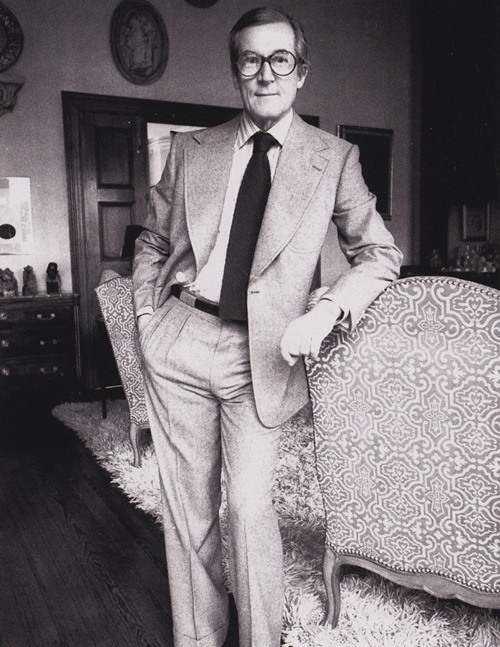

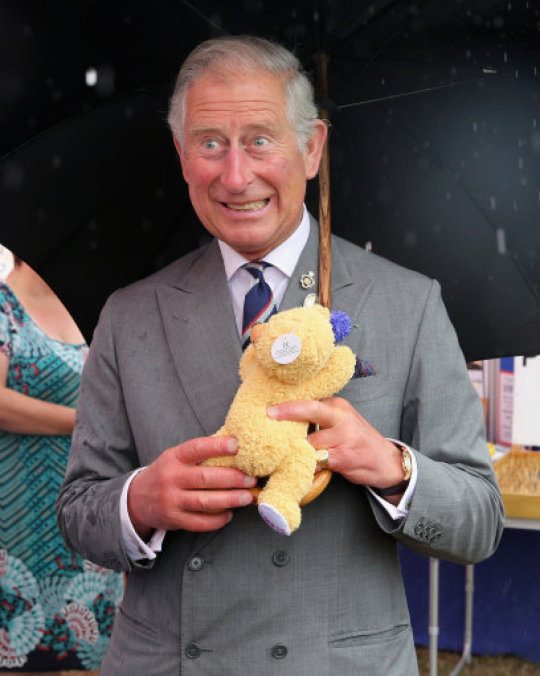

In the 1980s, he started hitting his stride, switching from single- to double-breasted, a style he has stuck with to this day. His double-breasted coats are always paired with a tiny four-in-hand knot and semi-spread collar (generally considered very tasteful).

In 2012, GQ named Charles "Best Dressed." Just a few years earlier, another pub named him "Worst Dressed." "Presumably, it sells publications," he said at London Collections, a tradeshow. "Meanwhile, I have gone on, like a stopped clock. My time comes around every 25 years."

The thing to understand about Charles' style is that he gets most of his non-military clothes made for him by Anderson & Sheppard and the independent cutters associated with that style, such as Tom Mahon (now at Redmayne) and Steven Hitchcock (who made the coat below).

These tailors specialize in something known as the drape cut.

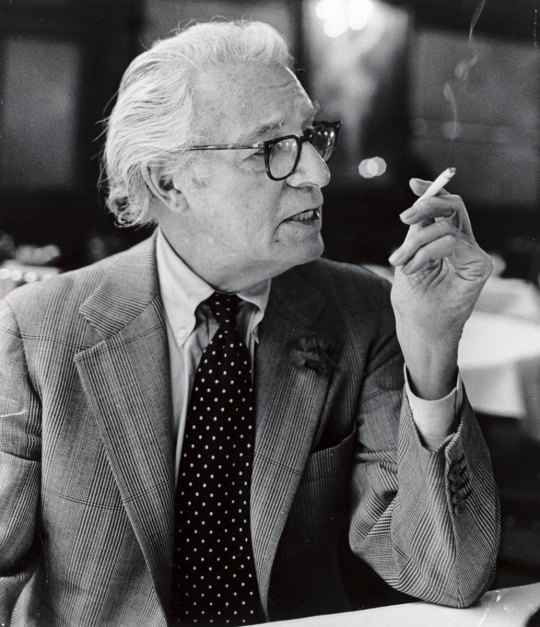

In the early 20th century, Dutch-English tailor Frederick Scholte noticed that when you cinch up the belt on a guard's coat, it puffs up the chest and makes the wearer look very masculine.

In the early 20th century, Dutch-English tailor Frederick Scholte noticed that when you cinch up the belt on a guard's coat, it puffs up the chest and makes the wearer look very masculine.

Scholte liked this effect and incorporated it into his tailoring. His coats featured a slightly extended shoulder and a fuller, rounder chest. The chest piece—a wirey horsehair cloth—was cut on the bias and inserted into the chest to give it some roundness.

Without delving into technical details that will bore most people, these coats were cut very "straight" (as opposed to "crooked"). Combined with a fuller chest and a dart that didn't quite make it to the armhole, this created excess material that "draped" along the armhole.

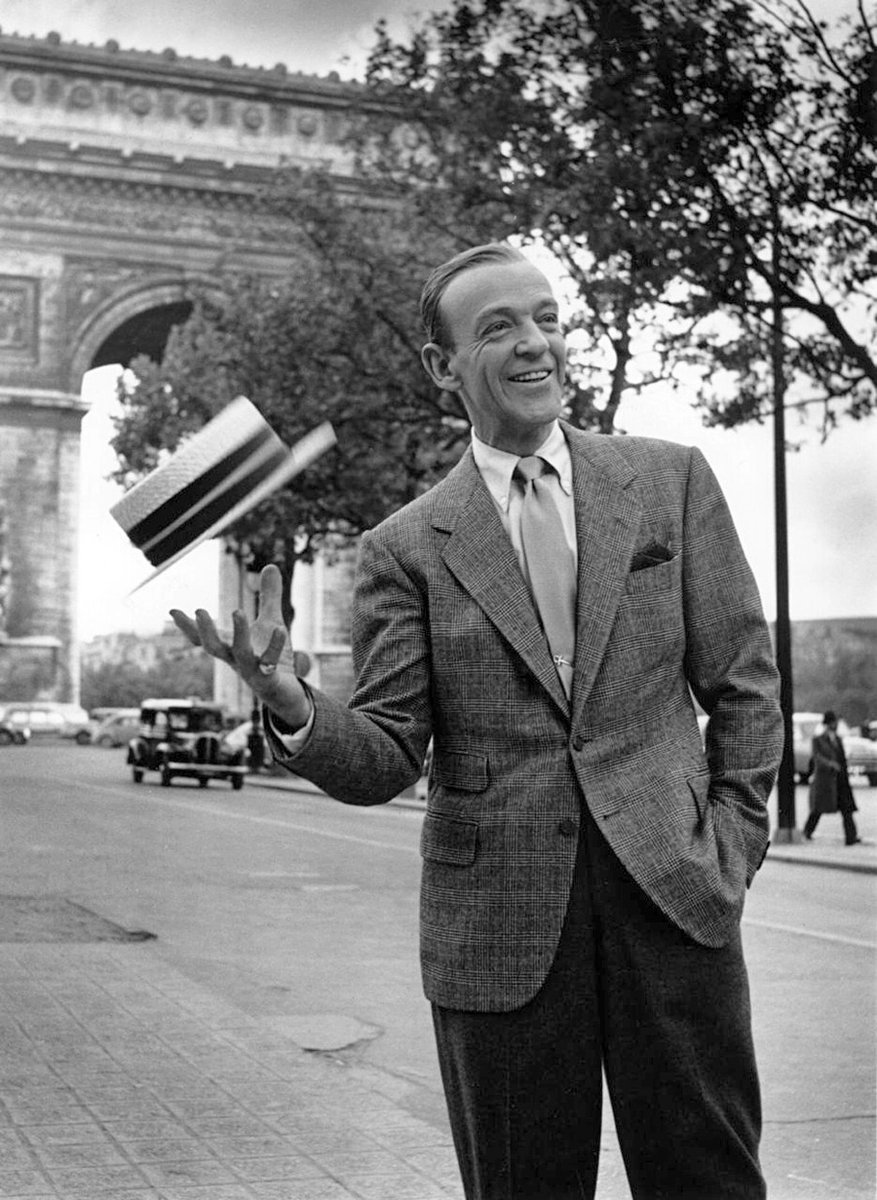

This effect is why this style is known as the drape cut. Scholte would go on to train Peter Gustaf Anderson, co-founder of Anderson & Sheppard, one of the most famous Savile Row firms. A&S would go on to dress stars like Noël Coward, Gary Cooper, and Fred Astaire.

The drape cut is one of Savile Row's most distinguishing cuts. It is defined by its soft, sloping shoulder and fuller, rounder chest. Historically, it was also made with a slightly curved lapel. The draping along the armhole is easier to spot on thin worsteds than heavy tweeds

You can really see the difference when you place a clean chest (pic 1) next to a drape cut (pic 2). Notice how the first suit has a chest that sits close to the body. The second is rounder and fuller. The advantage of the second is that it can confer a V-shaped silhouette.

The curve on a lapel is known as a belly. In tailoring, a lapel can be made:

1. With a little belly

2. A lot of belly

3. Straight (no belly)

4. So straight that it looks almost convex (popular in Florence, Italy). Notice how the curve forms a half-moon with bottom of the coat

1. With a little belly

2. A lot of belly

3. Straight (no belly)

4. So straight that it looks almost convex (popular in Florence, Italy). Notice how the curve forms a half-moon with bottom of the coat

Ok, so we've established the drape cut. Along with his penchant for double-breasted jackets, this is what defines Charles' style. Except for his military clothes, Charels mostly wears a soft shoulder, fuller and rounder chest, and slightly curved lapel.

Fred, the cutter who made all the menswear in The Crown, doesn't specialize in the drape cut. However, he's more flexible than most tailors, which is why he's often hired to work on film and TV projects.

The Crown stays true to many of the larger points of Charles' style. They put the younger Charles in single-breasted jackets and the older Charles in double-breasted jackets. The shoulder line is reasonably soft and sloping. The fabrics also reflect Charles' taste.

Fred also does a resonably good job of imitating Charles A&S drape cut. But here's where we get to an important point in tailoring:

A tailor is not a photocopy machine. They will never be able to copy something exactly. Every tailor has their own way of making things.

A tailor is not a photocopy machine. They will never be able to copy something exactly. Every tailor has their own way of making things.

This is not just true of Fred, but even of modern A&S. When you look back at those old A&S coats, many were made by cutters and tailors who have either since retired or passed away. It's more important to think about the hands that lay on a garment, not the label.

When choosing a custom tailor, it's best to look at their house style and stay close to it. This will result in less risk and disappointment. Every tailor has their own way of making things, and it's like their thumbprint on a garment.

Fred did his version of the drape cut, but his version doesn't have the same roundness as the originals. Notice the roundness on Charles' chest. West's version is nice—soft shoulder, DB closure—but is not as round. This has to do with the pattern & making.

The lapels were also often not as bellied. Even when cutting for private clients, Fred typically does a very straight lapel. The combination of the jacket's lapel and collar results in a much more angular look. The difference is evident when you compare these pics.

I spoke to Fred last year about this project, and he said that he and the costume department both agreed that they wanted to capture the general ideas of Charles' style, but weren't looking to make exact replicas. Which I think is reasonable.

He also noted that you can't replicate the same exact look on different bodies. Charles is 5'10"; Josh O'Connor is 6'1". Edward VIII was 5'7"; Alex Jennings is 6'1". That's a 5" difference! Replicating the same drape cut will look more off on him than doing something slimmer.

Ultimately, I think they did a great job. I'm told that even the ski suits were bespoke. The point of this thread is to help point out some of the subtle details in tailoring, which hopefully go beyond The Crown and allow you to notice things like details and silhouettes IRL

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh