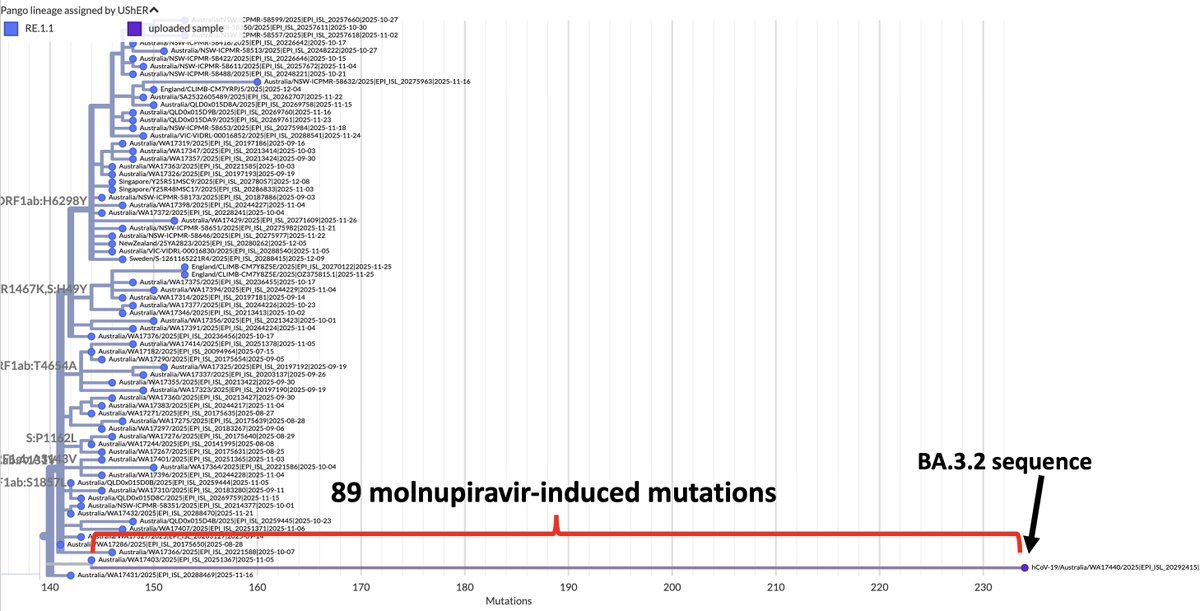

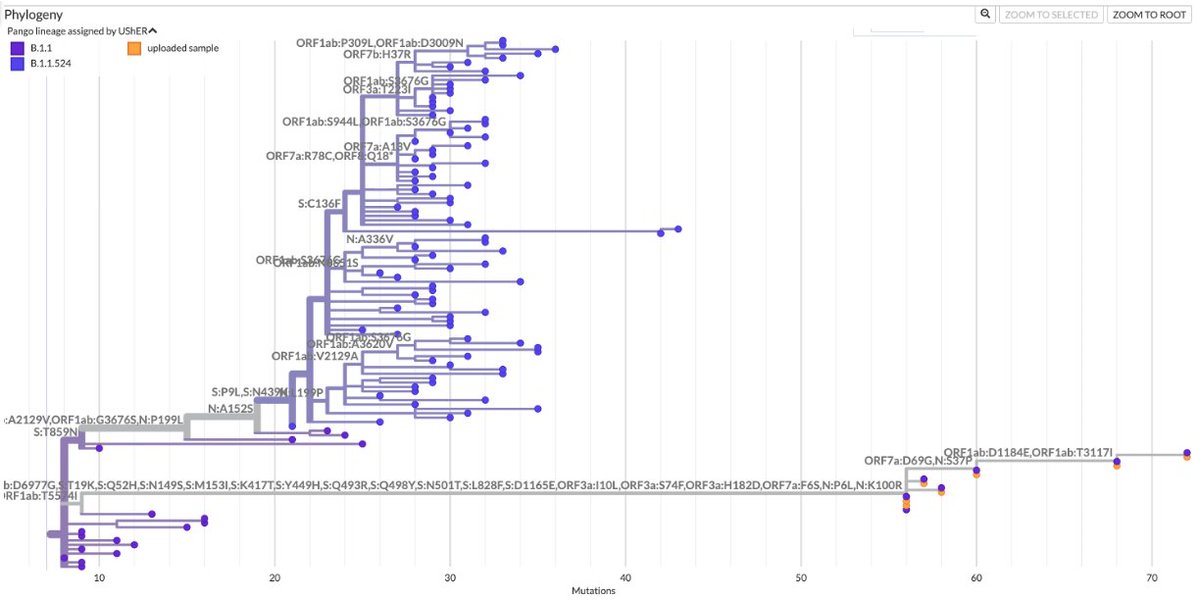

Ran into what looks to me like the first very good candidate for deer-to-human transmission. Below is the Usher tree containing it. It's the one on the right.

Before going into this seq's details, a brief description of the characteristics of deer sequences I've seen. 1/20

Before going into this seq's details, a brief description of the characteristics of deer sequences I've seen. 1/20

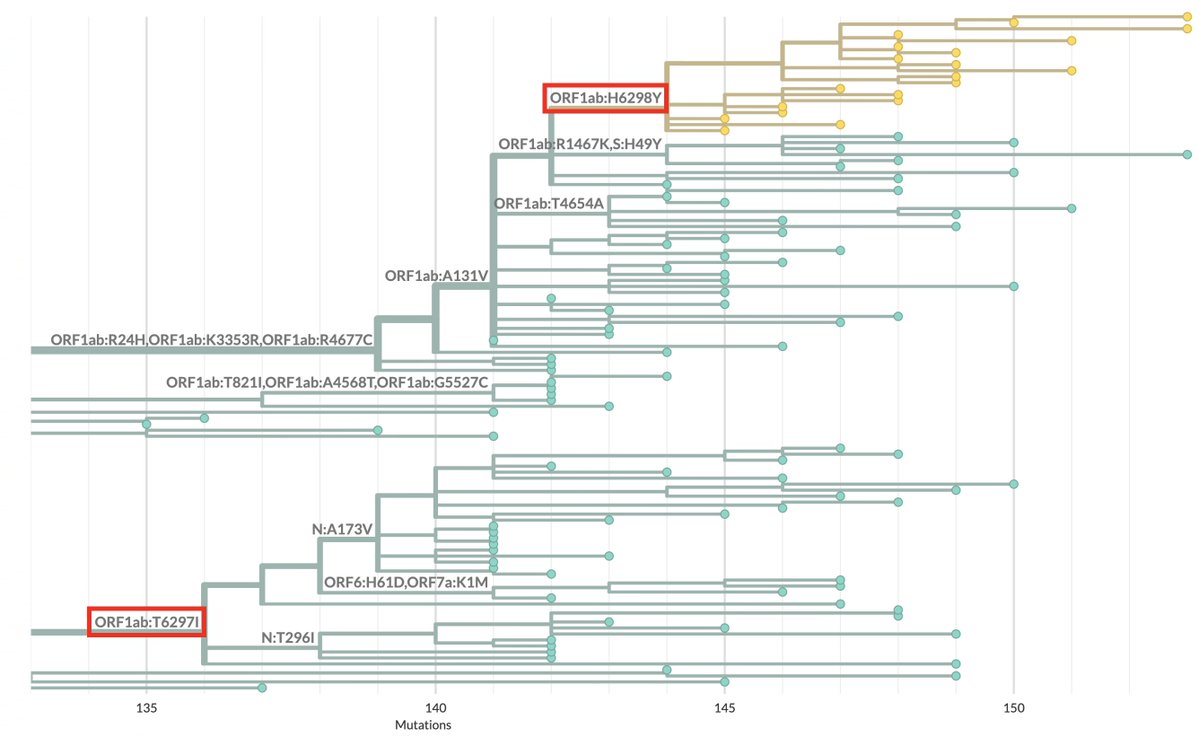

The branches leading to deer sequences are quite long. They also tend to be of variants that disappeared from circulation in humans many months ago.

The Alpha deer tree below is pretty typical. Note the most closely related human sequences are from ~6-7 months prior. 2/20

The Alpha deer tree below is pretty typical. Note the most closely related human sequences are from ~6-7 months prior. 2/20

The Gamma tree below is the most extensive deer-seq tree. These are long branches. I doubt if there are *any* human Gamma sequences with over 75 mutations from wild-type, for example. Here there are several. But it's not just the number of mutations that distinguish these. 3/20

The types of nucleotide (nt) mutations in deer sequences are unlike any human seqs. Deer sequences overwhelmingly consist of C->T mutations. This is also the most common mutation in humans, making up ~42% of mutations. See @jbloom_lab chart below. 4/20

But deer sequences are in another league entirely. It’s common to see C->T make >75% of nt mutations in them. I made Usher trees for all deer seqs, opened the first 6 trees, & selected 1 seq from each w/many mutations (less dropout) & no obvious errors or recombination. 5/20

Counting only the mutations that took place within the deer part of the tree, I did an amateur analysis of the types of nt mutations, as well as the amino acid (AA) substitutions in 6 deer seq. Non-synonymous nt mutations are ones that change the AA. Results below. 6/20

Combined stats for 6 deer seqs 👇

5 things stand out:

1) Very large # of mutations

2) Extremely high C->T content (79.4%)

3) Deer *really* like the synonymous C7303T

4) Very low % of non-synonymous mutations (44.8%)

5) Few spike mutations, almost none in RBD 7/20

5 things stand out:

1) Very large # of mutations

2) Extremely high C->T content (79.4%)

3) Deer *really* like the synonymous C7303T

4) Very low % of non-synonymous mutations (44.8%)

5) Few spike mutations, almost none in RBD 7/20

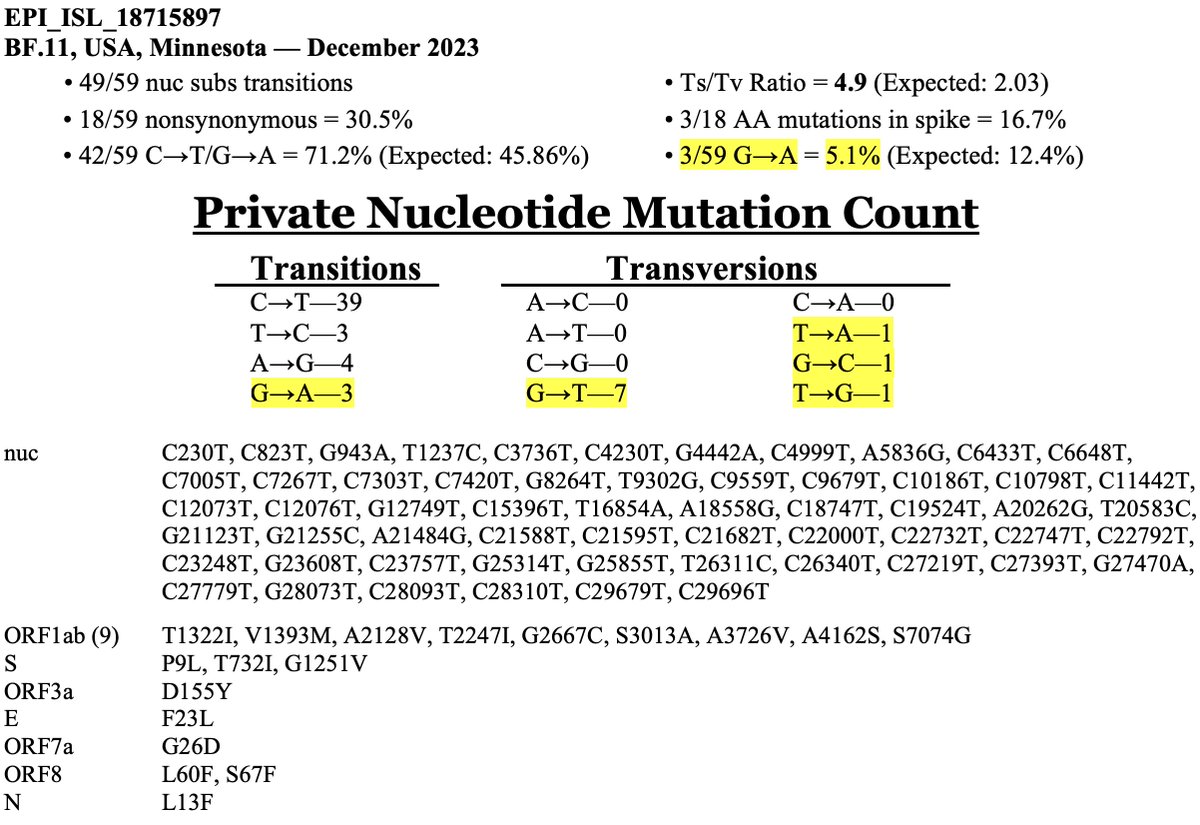

How does the BF.11 deer-to-human candidate compare in terms of number & type of mutations? It's very similar to deer seqs—more similar than any human seq I've ever seen.

Very low non-synonymous %, very high C->T content, few spike mutations, zero in RBD—and C7303T! 8/20

Very low non-synonymous %, very high C->T content, few spike mutations, zero in RBD—and C7303T! 8/20

It's also, like most deer sequences, from a variant that ceased circulating in humans many months ago.

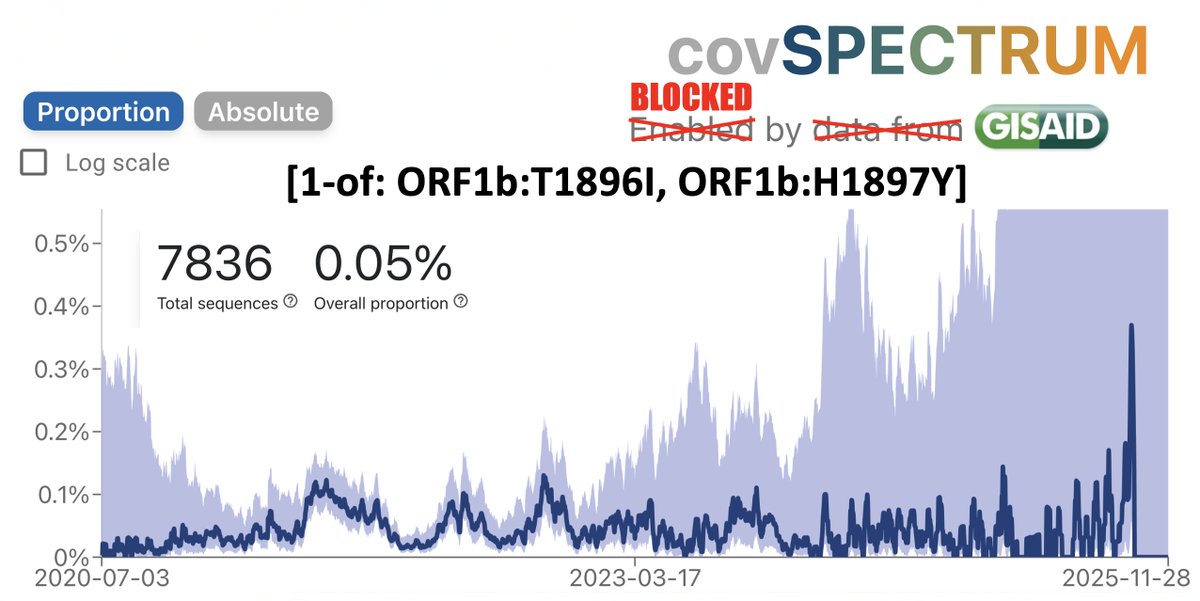

Why the big deal about C7303T? This is a rare mutation in humans—in just 0.07% of sequences. But it’s in about 50% of deer sequences. 9/20

Why the big deal about C7303T? This is a rare mutation in humans—in just 0.07% of sequences. But it’s in about 50% of deer sequences. 9/20

What about other private nt mutations in this seq? I ran all deer seq through Nextclade to extract their private mutations—ones not shared with other sequences in the tree—and compared them to their overall prevalence in human sequences. To be clear..... 10/20

...the comparison is *not* apples to apples. An equal % in each means a mutation is likely *far* more common in deer than in human seqs.

What we'd really like is the # of times a mutation has independently emerged in humans & in deer. But I don't know how to do that. 11/20

What we'd really like is the # of times a mutation has independently emerged in humans & in deer. But I don't know how to do that. 11/20

Overall, the similarity of this sequence to past deer sequences is amazing to me. There's been much talk about reverse zoonosis, but this is the first sequence I've seen that really has the look of it. Nothing else comes close. 12/20

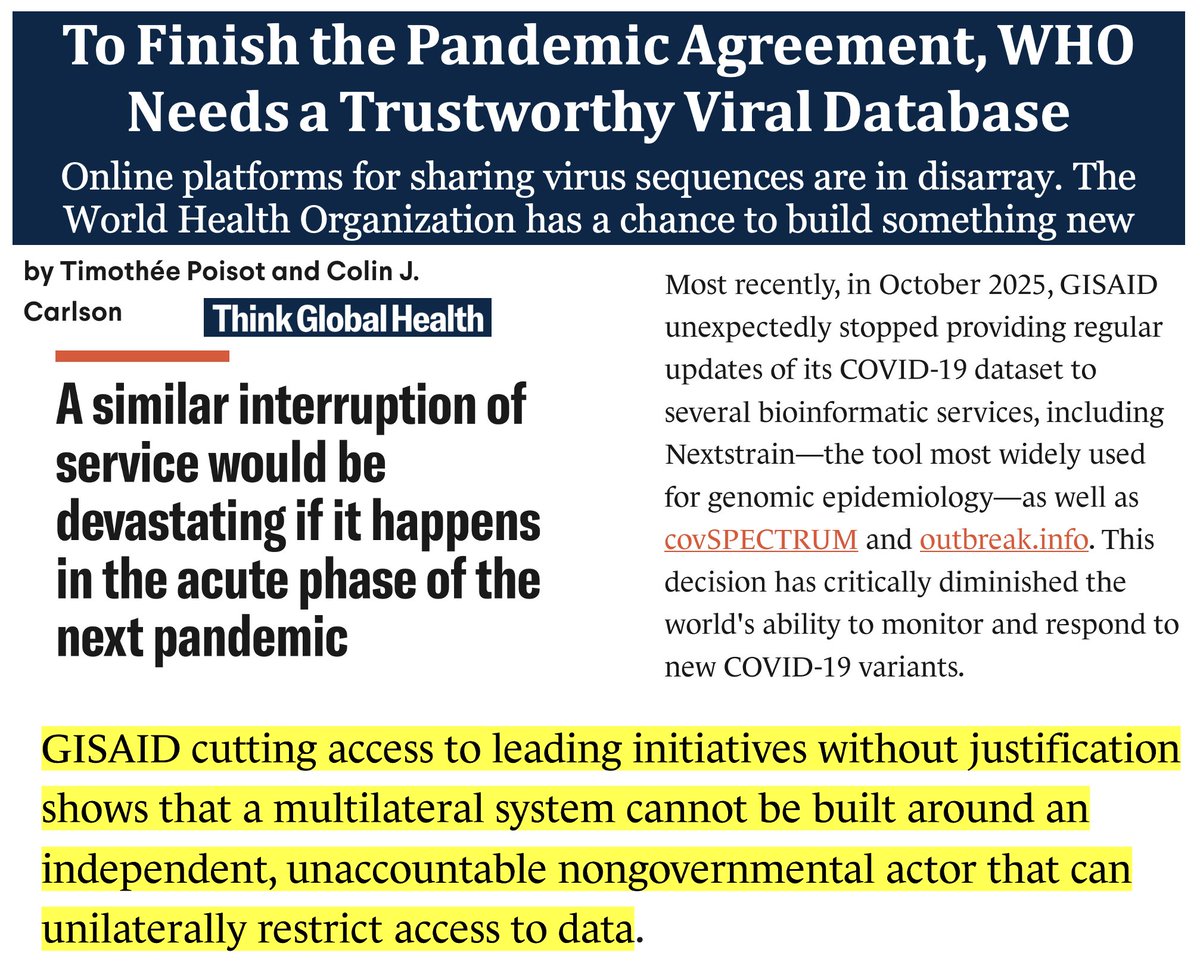

What is the risk of deer-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2? It's not zero, but I think it's far less worrisome than, e.g., the risk of a molnupiravir-creation hitting a mutational jackpot & spreading. See @sergeilkp & @DarrenM98230782 on this topic. 13/20

These deer sequences have almost no antigenically important spike mutations. None that I've seen would have the slightest chance of circulating in humans. The molnupiravir sequences, on the other hand, often have many spike mutations & at least appear to be quite fit. 14/20

Of course we only have a small sample of deer sequences—almost none Omicron—so there could be more sinister SARS-CoV-2 variants lurking out there.

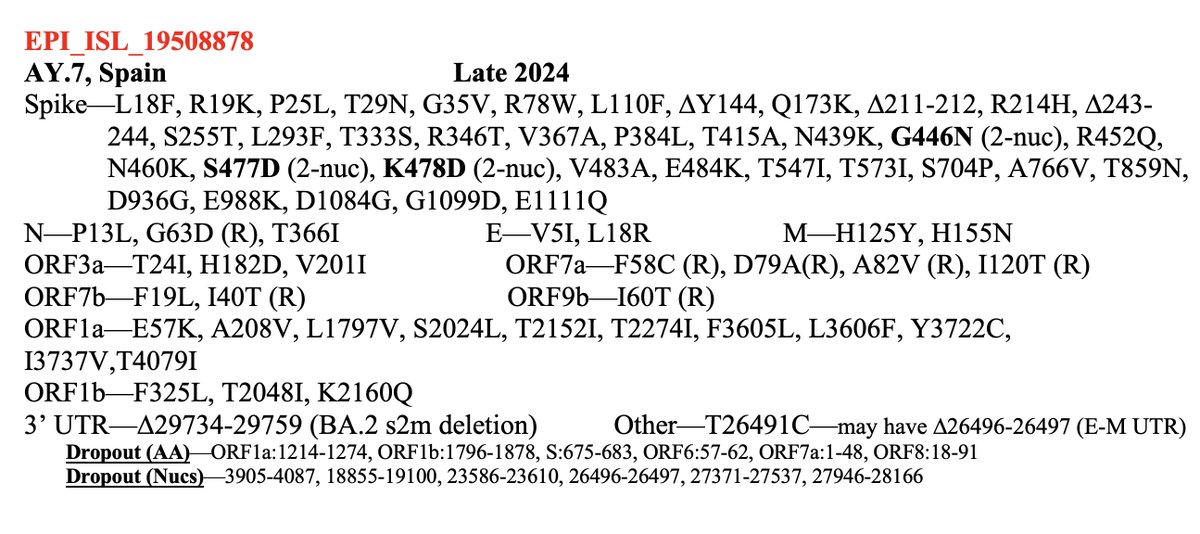

Finally, how do we know this sequences is not a MOV sequence? 15/20

Finally, how do we know this sequences is not a MOV sequence? 15/20

I assumed when I first saw it that it was a MOV creation. Branches like this—with 59 private mutations—are almost always MOV creations. Rarely, they're very old variants from a chronic infection—virological demons of the ancient world, which this is decidedly not. 16/20

But a cursory examination of the mutations makes it clear this sequence is not MOV-related. First, the most distinctive MOV mutation, G->A, is less common than usual here. There are also more transversion mutations that we typically see in a MOV sequence. 17/20

Finally, MOV preferentially causes mutations in certain nt contexts. For example, G w/an upstream T & downstream C—TGC—is a favored context, but AGA is a very unfavorable context. Similarly, some contexts favor MOV-driven C->T mutations, while others don’t. 18/20

The preternaturally talented @theosanderson created a tool to examine the nucleotide contexts of mutations & assess the likelihood they were caused by MOV. It’s not uncommon to see probabilities of 0.99 or greater in MOV seqs. Probability for this sequence = 0.001 19/20

Last, I want to give a shout out to the @nextstrain team for creating Nextclade, which features heavily in all SARS-CoV-2 work I do. I am in great debt to @ivan_aksamentov, @CorneliusRoemer, @richardneher, & whoever else created & maintains this brilliant tool.

20/20

20/20

Addendum: Thanks to @midnucas for suggesting I include the paper below. I had not read this paper, but they document 3 sequences that clearly involved human-deer-human transmission. A1/4

https://twitter.com/midnucas/status/1743110564090675308

When looking at the Usher tree for one of the human-deer-human sequences the authors identified, I came across 2 nearby sequences that to me seem likely examples of deer-to-human transmission.

It's amazing to me that this kind of transmission happens at all. A2/4

It's amazing to me that this kind of transmission happens at all. A2/4

One of these clusters has an odd feature: it also involves 3 lion sequences from a zoo in North Carolina. How did a variant originating in wild white-tailed deer manage to infect lions in a zoo? I can't imagine many people—or any deer—have close contact with lions. A3/4

But @PeacockFlu suggested that perhaps these lions were fed deer (leftovers from hunters' takes?) & were infected that way. That's the only thing that makes sense to me.

Does anyone know if this is common practice at zoos in North Carolina (or elsewhere)? A4/4

Does anyone know if this is common practice at zoos in North Carolina (or elsewhere)? A4/4

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh